Steadily, tentatively, light is creeping back. The snowdrops have been sighted at the Botanic Gardens. There are still a few dregs of colour in the sky after the work day is done. Slowly we begin to emerge from hibernation, and what better way to celebrate this than by letting you know about some of the art exhibitions I’m most looking forward to this year.

Over my years of writing about art (Encounters Art is four years old in May this year!) there are a few things I’ve learnt. Unfortunately, you have to be organised. If you see something you like the look of, make sure you go to see it close to the start of the run. Otherwise, you just won’t get round to it. I have learnt this the hard way far too many times. Even with shows that will be on until 2026, it’s better to strike while the iron’s hot. So, let’s all get our diaries out and get these dates marked! Exhibitions are listed in chronological order.

The Scottish Colourists – Radical Perspectives at Dovecote Studios

Friday 7 February to Saturday 28 June

This looks like a fascinating show, hosted by Dovecot Studios – one of the most underrated places to see art in Edinburgh. The Scottish colourists were a group of four painters around in the early 20th century, who were influenced by the time they spent in France. This exhibition shows their work alongside Matisse and Derain, as well as Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant from the Bloomsbury Group. I LOVE this era of painting but don’t know much about this much beloved group of Scottish artists, so I’m looking forward to learning more. General Admission tickets are £12.

Jerwood Survey III at Collective

Friday 28 February to Sunday 4 May (Wednesdays – Sundays)

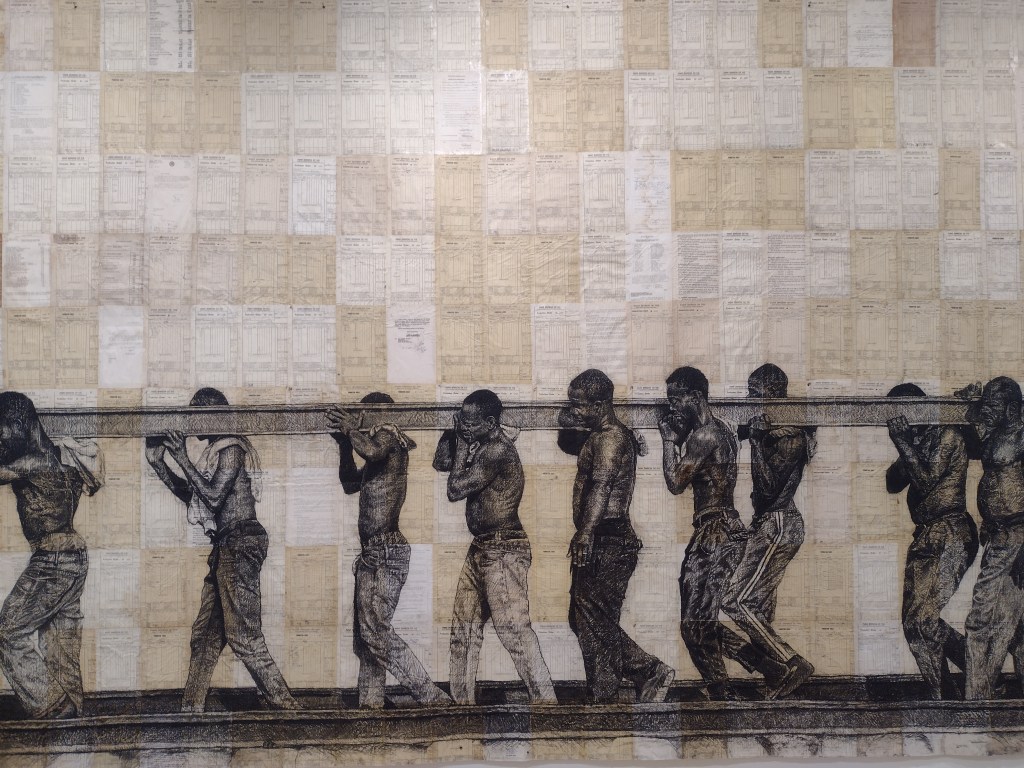

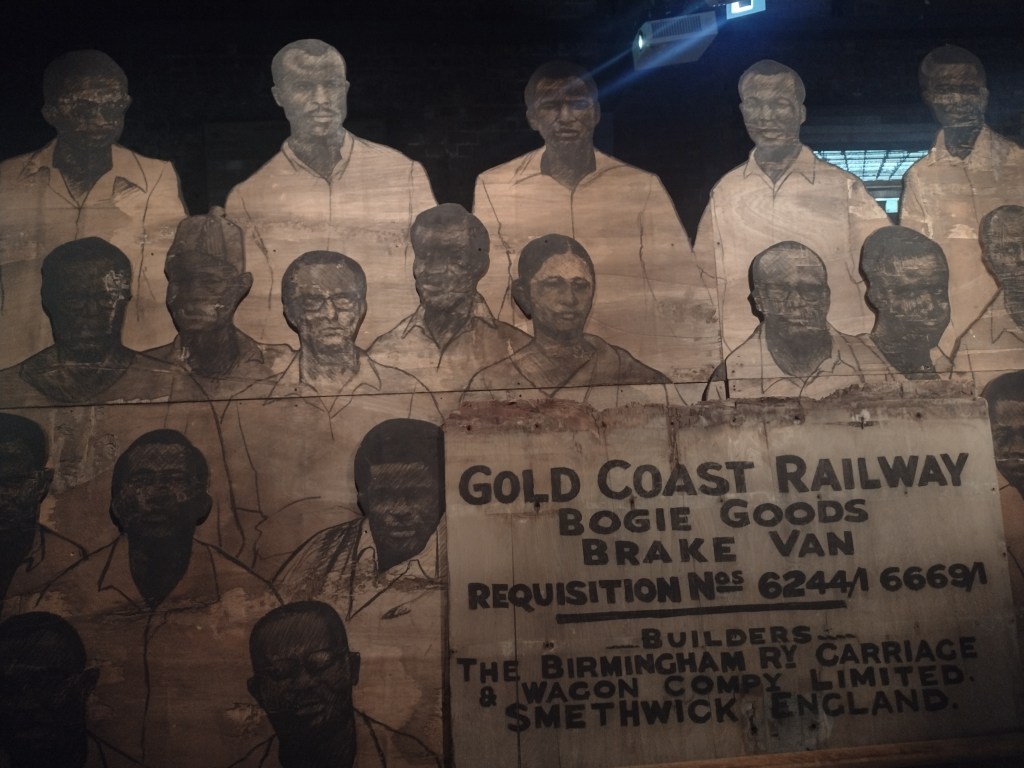

Collective, perched high atop Calton Hill, is an art space I feel I have neglected. I think I’ve seen a few shows there that didn’t quite land with me, which have made me lazy about climbing that hill. However, I intend to rectify that this year. Their first show of the year is the Jerwood Survey III. This initiative brings together ten emerging, early career artists who have been recognised and selected by leading artists for the outstanding work they are creating. Collective is the final stop on this exhibition’s tour, it has been to London, Cardiff and Sheffield. I love the concept of a touring exhibition – several feature in this list. Themes addressed by the artists include colonialism, climate change, healing, gender, sexuality, folklore and spirituality. So this is one to visit when you’ve got brain space and energy for art that can challenge, provoke and make you encounter the big topics. Entry is free, though a £5 donation is suggested. Please donate if you can afford to do so: these are trying times for the arts in Scotland and exhibitions are expensive to run. Collective is open Wednesday-Sunday.

Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood at Dundee Contemporary Arts

Saturday 19 April to Sunday 13 July

I love Dundee Contemporary Arts. If I lived in Dundee I’d be there all the time at their cinema which seems to only show interesting movies (I just checked, it’s also showing Mad About the Boy, which is fine with me). The Acts of Creation exhibition has been on my radar for a while. Hettie Judah, the curator, has done an amazing job of advocating for artists who are also mothers. She uses her Instagram as a platform for artist-mothers work and I love the idea of an exhibition that interrogates motherhood in all its complexity. Featuring some pretty big hitters of the art world, including Tracey Emin, Paula Rego and Chantelle Joffe, I’m so glad this is finally coming to Scotland – it began at the Hayward Gallery in London and has also been at the Millenium Gallery in Sheffield. I think tickets are free, can’t see anything to suggest otherwise. The gallery is open Wednesday-Sunday.

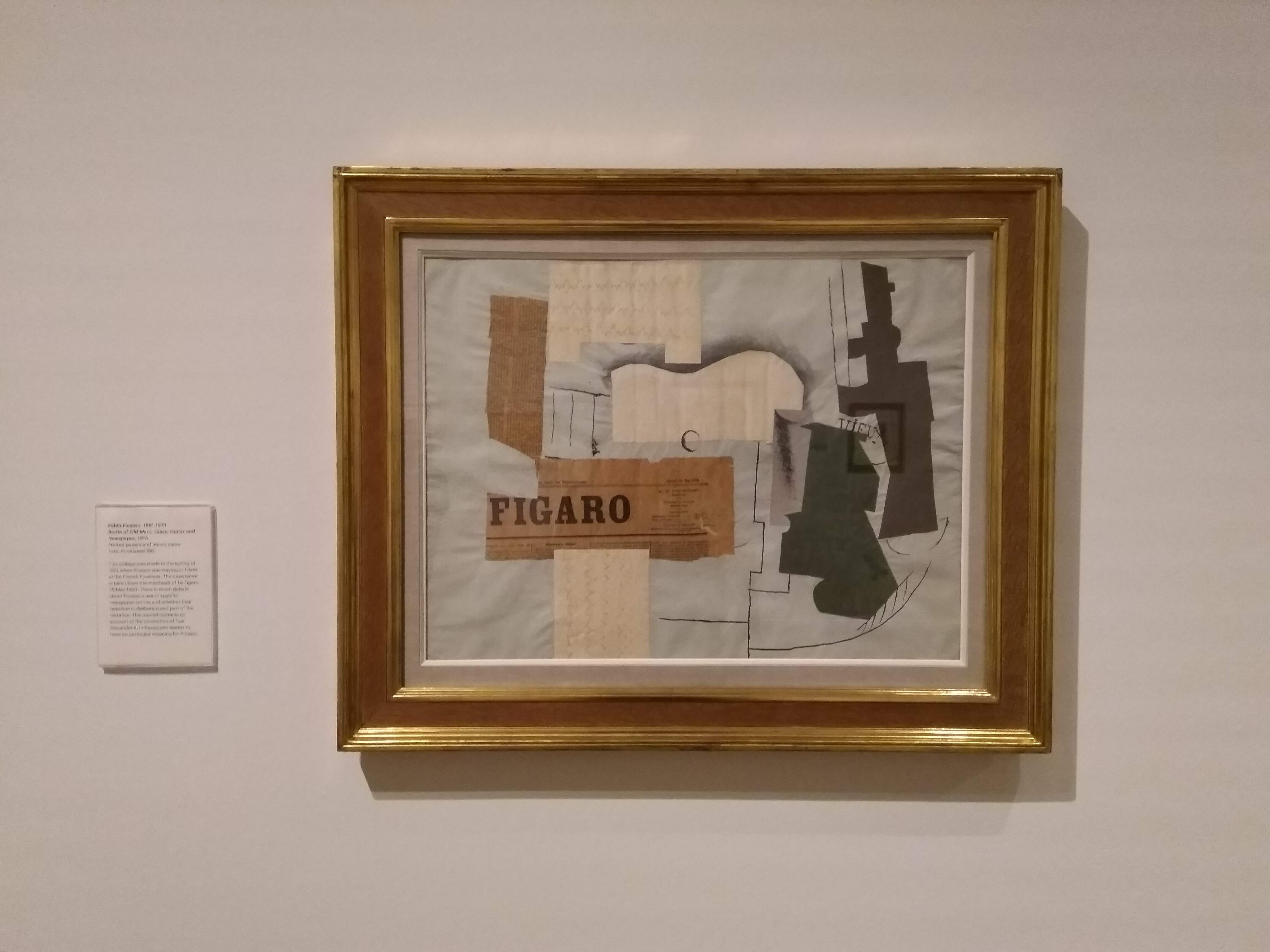

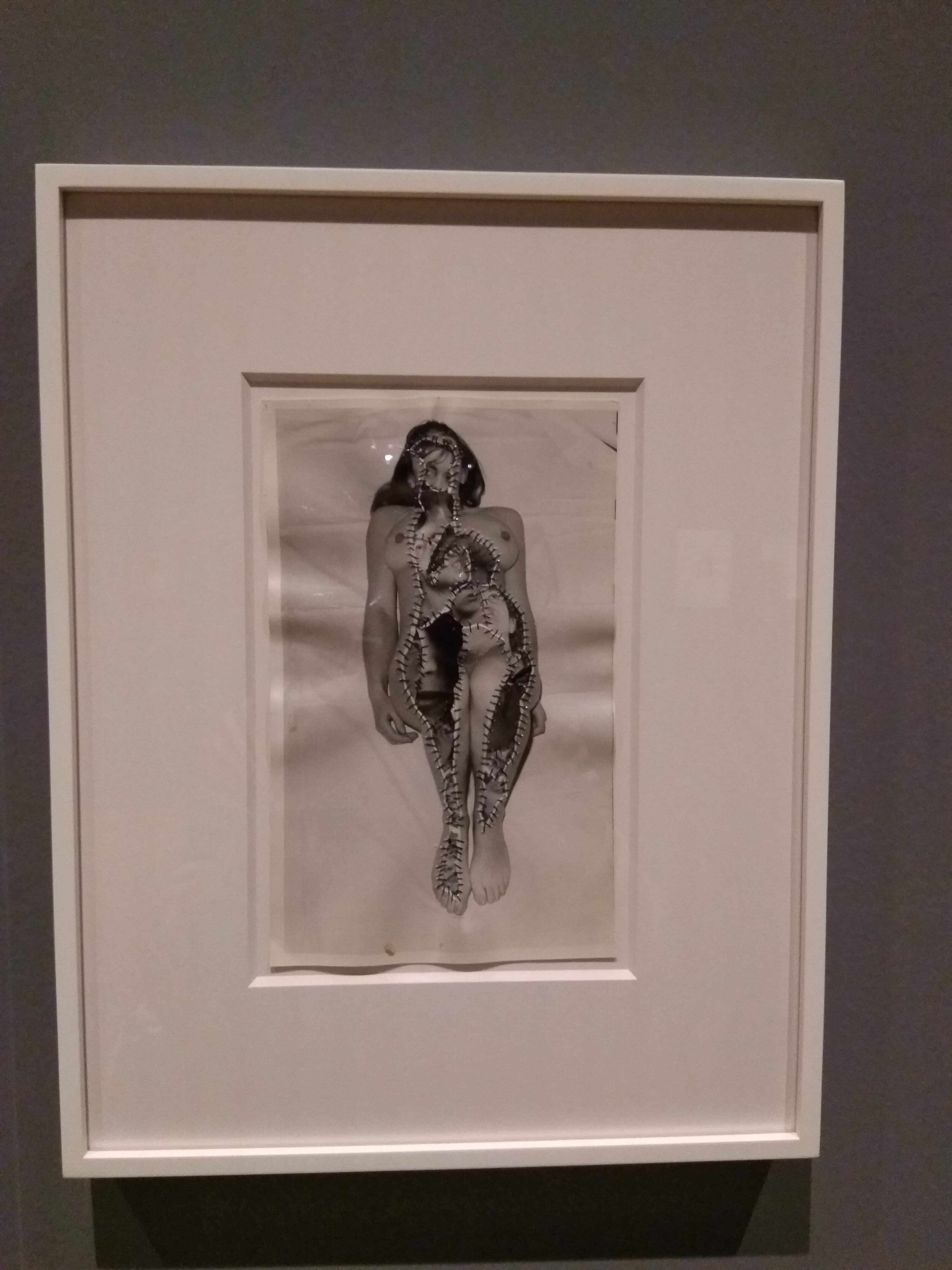

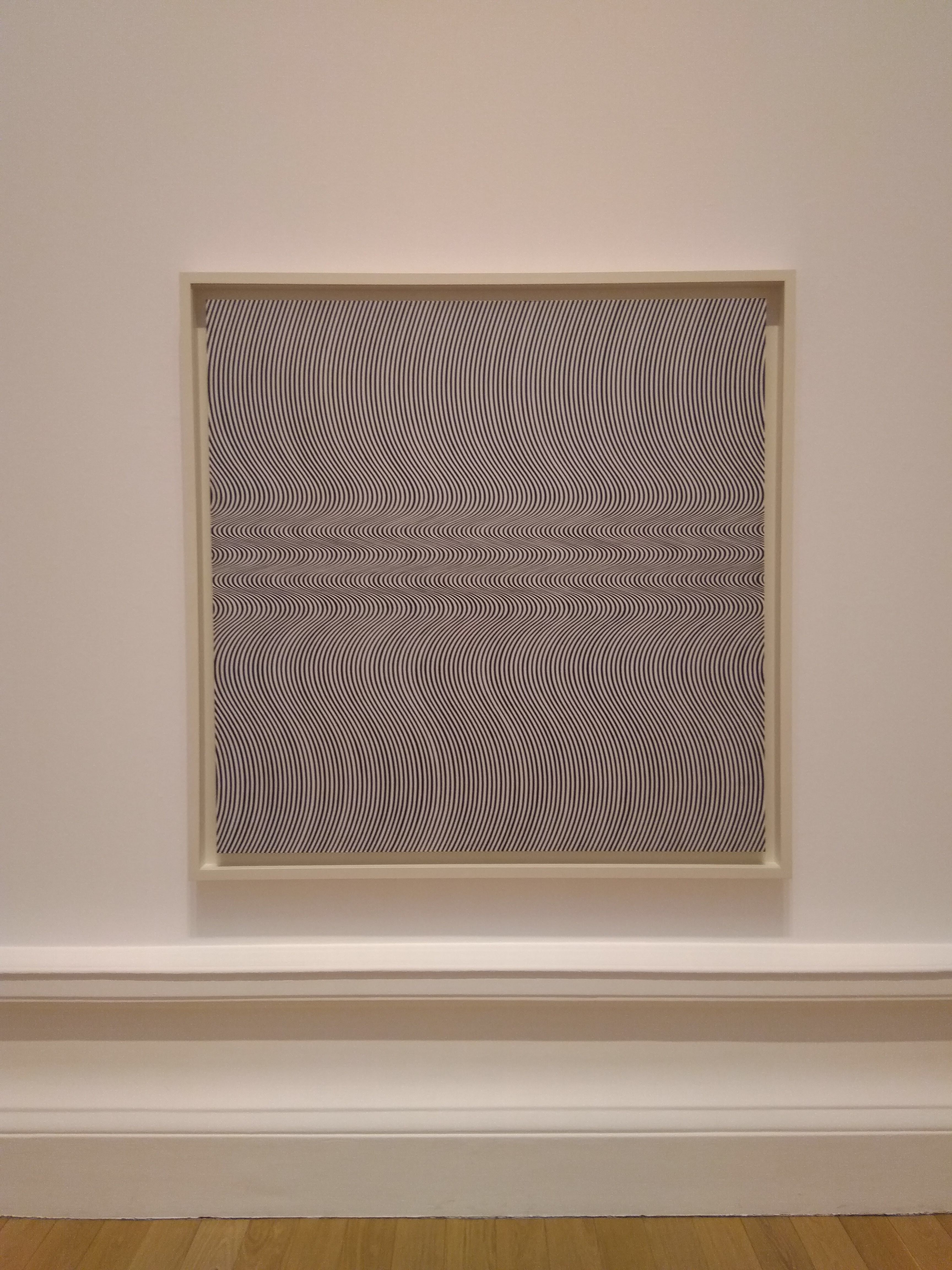

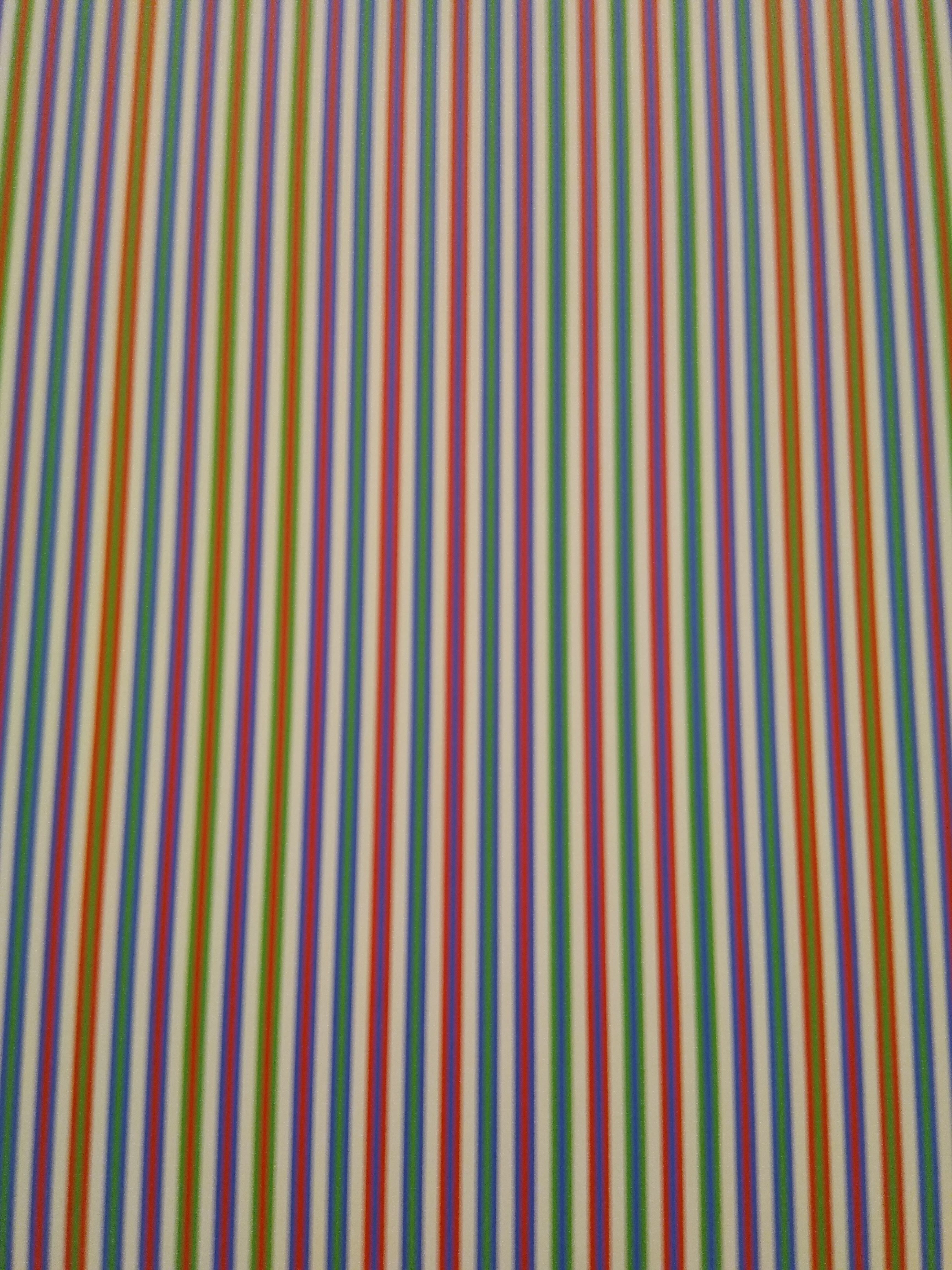

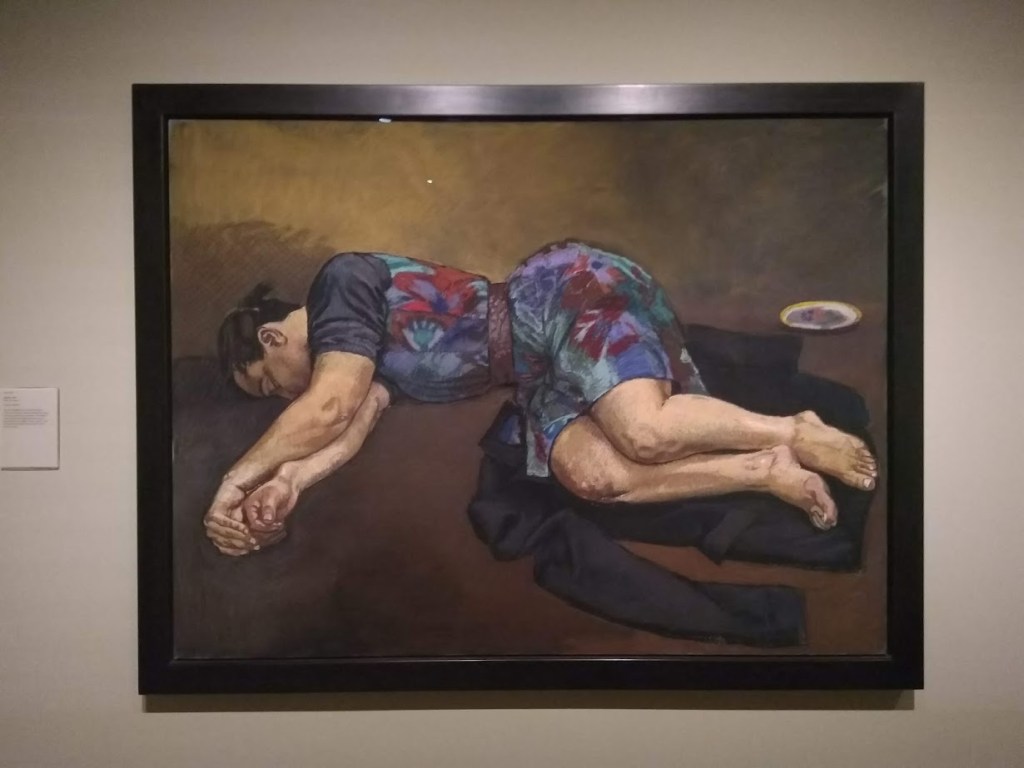

Photographed at the ‘Obedience and Defiance’ show at Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, 2019

The murals at Mansfield Traquair

This is another one on the “I’ve been meaning to go for years but never got round to it” list. The Mansfield Traquair Centre is referred to by some as ‘Edinburgh’s Sistine Chapel’, which is a pretty big claim. Originally it was a Catholic Apolostolic Church, completed in 1895. The building’s most famous feature is its murals, painted by the renowned Phoebe Anna Traquair in the 1890s. The space is currently used for weddings, parties and corporate events, but they host open days and tours usually on the second Sunday afternoon the month, with more dates added during the Fringe. Free – more info on tours and dates here.

Linder: Danger Came Smiling at Inverleith House, Royal Botanical Gardens

Friday 23 May to Sunday 19 October

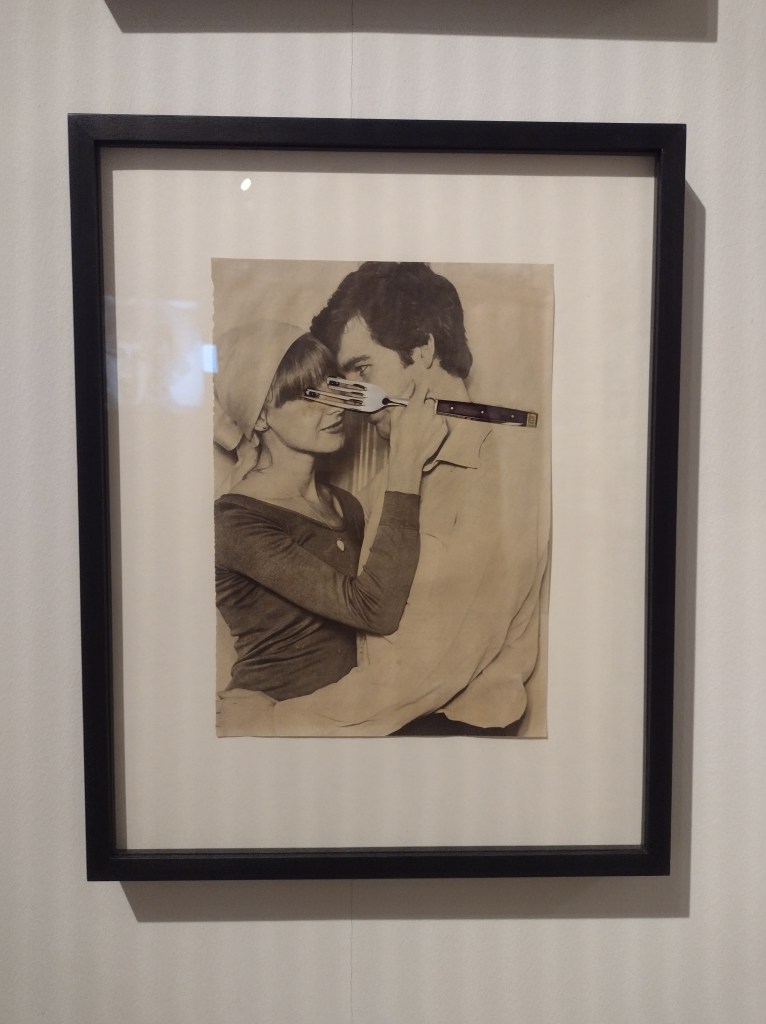

I was really excited hearing about this show and was trying to figure out when I could get down to London to see it at the Hayward Gallery when, lo and behold I find out it’s coming to Inverleith House! This will be a remarkable show – a retrospective of feminist icon Linder’s work in the year she turns 70. This weekend in the Guardian there was a long and fascinating interview on how she uses trauma and porn to inform her art, and I definitely think she’s going to ruffle a few feathers of people visiting the Botanics! She’s a very cool punk artist who does incredible collages. This one, of a woman seemingly in a picture of domestic bliss, is gouging her eyes out with a fork (I saw it at the Women in Revolt exhibition at the National Galleries of Scotland earlier this year). I can’t wait to see more of her provocative and radical work. Not sure on ticket details and pricing yet – watch this space.

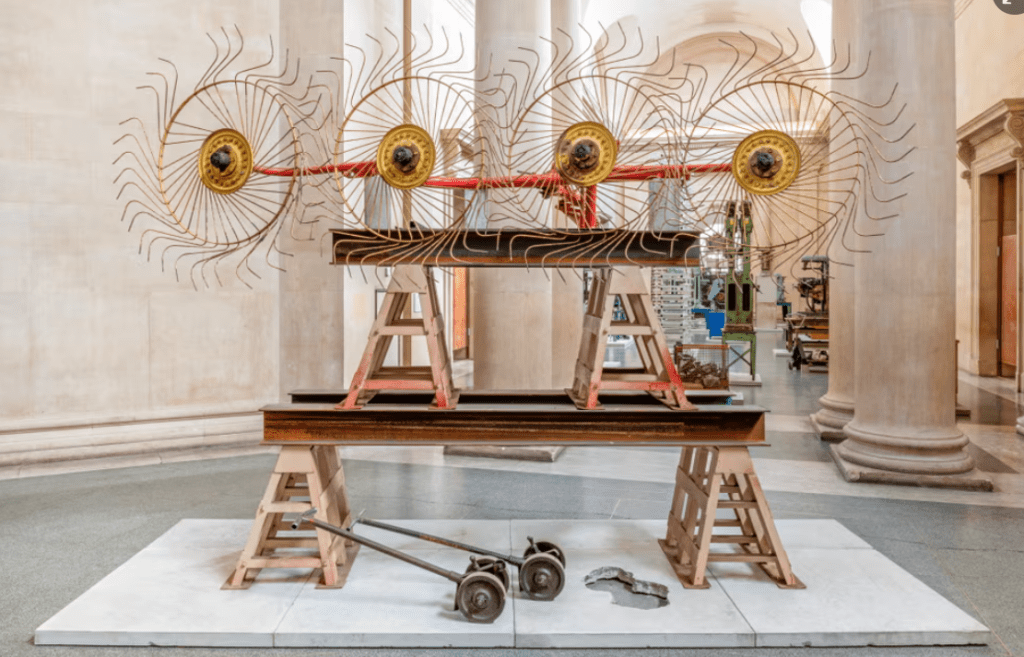

Mike Nelson at Fruitmarket

Friday 20 June to Sunday 28 September

I first came across Mike Nelson’s work at a huge exhibition at Tate Britain in 2019, which art critic Laura Cumming referred to as his ‘all time masterpiece’. I’ll be interested to see where he goes from there. His work features huge installations, often formed from scrap metal and defunct machinery. For this exhibition, Nelson will be using Fruitmarket’s bare Warehouse as a studio in the weeks preceding the exhibition, and I think his work will marry well in that space, where the art has to take on an industrial scale. Fruitmarket exhibitions are free.

Andy Goldsworthy – Fifty Years at the Royal Scottish Academy

Saturday 26 July – Sunday 2 November

You have probably seen an Andy Goldsworthy artist without having even realised it. Last week at the Botanic Gardens a slate structure that looked like an old cairn caught my eye, and it turned out to be a large sculpture by him. His work, Coppice Wood, at Jupiter Artland is probably my favourite there. He uses nature and the natural elements of our world to craft artwork that is simultaneously vast in scale and understated in tone. The exhibition brings together more than 200 works including photographs, sculptures and expansive new installations built in-situ and specially created for this exhibition. Unlike some of the other shows on this list, it’s only being exhibited in Edinburgh – part of Edinburgh Art Festival – but one to visit before the Fringe crowds arrive, if you can. Full price tickets are £19. Read to the end for my tip on getting cheaper tickets.

Jupiter Rising x EAF

Date TBC

Those of you who’ve been reading the blog for a while know I’m a big fan of both Jupiter Artland and Edinburgh Art Festival. But I’ve never made it to their big collaborative summer party/festival, Jupiter Rising x EAF. This time, I’m determined to be there. It brings together experimental music, performance, poetry and art. Essentially it sounds like a big fun queer art party. Does anyone want to give me a lift?

Pittenweem Arts Festival

Saturday 2 to Saturday 9 August

This is an event I’ve been meaning to go to for a while, and it’s in one of my favourite corners of Scotland. Pittenweem is one of the prettiest coastal villages in the East Neuk of Fife. The annual art festival brings the joy of art to everyday spaces – homes, garages and sheds. I think it sounds like a lovely way to spend a day, wandering along the Fife Coastal Path (hot chocolate at the Cocoa Tree Cafe, lunch at the East Pier Smokehouse) then browsing some art, and chatting to artists, maybe purchasing something new for your home too.

Art Walk Porty

6 to 14 September 2025

OK I am biased with this one as I’m on the Board of the organisation, but Art Walk Porty is always one of the highlights of the art calendar in my year. It brings together artist residencies, with events, workshops, and the art houses, where people open up their homes to exhibit their art. While the programme is yet to be announced, this year marks 10 years since the organisation began, so it’s bound to be a packed and celebratory week. I am always in awe of how much the Art Walk team manage to deliver, and they recently managed to secure multi-year funding from Creative Scotland for the first time. Watch this space as more details of the programme emerge.

Rolled over from last year, I still want to visit Mount Stewart House in Bute and the Italian Chapel, Orkney. You can read more about my 2024 bucket list in last year’s blog post here.

Finally, I feel the list wouldn’t be quite complete without a nod to two exhibitions I am intending to see in London. Firstly, Kiefer/Van Gogh at the Royal Academy London (28 June – 26 October) which is sure to be astounding. My Masters’ Dissertation was on Anselm Kiefer and his retrospective at the Royal Academy in 2014 was one of my favourite shows I’ve ever seen. At Tate Modern, I’m hoping to see Do Ho Suh: Walk the House (1 May – 19 October). This is after encountering his work for the first time at the one of my favourite exhibitions of the 2024 at the National Galleries of Scotland. I’m very keen to see more.

Top tip: if you’re seeing lots of art this year, I’d recommend looking into buying a National Art Pass from the Art Fund, which currently costs £62.35 by direct debit. Almost every charging exhibition gives you a discount if you have the card, you get a cute quarterly magazine with interesting article and art news, and most importantly, you’re supporting the arts.

I’d love to hear what you’re looking forward to, and perhaps any major moments I’ve missed from my list! Feel free to get in touch using the comments, and don’t forget to follow me on Instagram to see if I make good on all these art ambitions for 2025.