A few months ago I was in the Self Help section of a bookshop. It isn’t a zone I am particularly familiar with, being a cynically-minded, stubborn sort of person. I had been searching for a specific book in the Art section ‒ much more familiar territory ‒ before realising I’d been looking in the wrong place: cue the obvious metaphor here.

The Artist’s Way: A Spiritual Path to Higher Creativity by Julia Cameron is a multi-million-copy worldwide bestseller. It’s something my sister read years ago, and she had gleaned a lot from it, but I’d never considered giving it a try myself. Until now. It was late Autumn, I hadn’t written anything for weeks, and creativity of any kind seemed an exhausting and far-off prospect. Along with the background of the never-ending pandemic slowly eating away at my sense of self, I could tell I was in a rut. Keen to bundle myself out of this rut by any means necessary, I decided to put my scepticism aside while attempting Cameron’s twelve-week journey which promised to ‘unblock my creative potential’. Yikes. Writing that down makes me physically cringe. But I’m doing my best to embrace the cringe, the daily freewriting, the imaginative exercises and the creative affirmations. Yes, these elements are all part of the process (some are a bit much).

Around the same time, I went to a wonderful wedding in Bristol, one of my favourite cities. With a strong culture of street art since the late 70’s, explored brilliantly at a recent exhibition at M-Shed, and the recent history of trundling Edward Colston’s defaced and disgraced statue into its harbour, Bristol is the kind of place where creative and political agency seem to fizz just beneath the surface. If there were ever a place to mix up my stagnant energy, then surely it was here, with time to myself and new places to explore.

Looking at art is one of my main ports of call when dealing with a whole range of emotions and feelings. I expect a lot from my interactions with art, but one of the best things is when these interactions surprise me. This kind of joyful surprise can be something incidental, like the unexpected shapes and surfaces in the city fabric captured by Matt Calderwood on Instagram, but if you want to be surprised at a gallery, you have to go in with little to no expectations and as little background reading as possible.

On the day I visited the Stephen Gill: Coming Up For Air exhibition at the Arnolfini I didn’t know that I’d end up being so enchanted with it. I almost ended up missing my plane back to Edinburgh because I was so absorbed (yup, I flew there, I’m a bad person). Stephen Gill is a Bristol-born, internationally-exhibited photographer who I didn’t know anything about before seeing this show, which is free and on until 16th January (omicron willing).

I skimmed through the first half of the first room, until I came upon his Audio Portraits, (1999-2000). These are portraits of people with headphones on, with what they’re listening to written below. I like it when artists can articulate a thought you’ve already had, but never known how to express. As someone who frequently listens to music while on the move, I love the feeling that I’m immersed in my own world. I can listen to Ariana Grande with no one judging me. I can stomp down the streets of Edinburgh listening to Rage Against The Machine’s Kick Out the Jams when I’m feeling angry or rebellious. I can silently sing along word-for-word with Joseph and His Amazing Technicolour Dreamcoat whilst commuting and no one suspects a thing. In Audio Portraits, Gill lifts the lid: he lets us into other people’s worlds. The people and the tracks won’t always match or be what you expect. This is the artwork that made me realise that I was going to enjoy the exhibition.

The next was the Billboards series from 2002-2004, where Gill has photographed the back of several billboards, showing the stark and frequently ironic contrasts between the aspirational notions of the advert and the reality surrounding it. L’Oréal Paris proclaims “you’re worth it” and backs on to a wet yard surrounded by corrugated iron, a tyre and some upturned shelving units. Noticing the unnoticeable, and allowing us to notice that magic too, is the photographer’s special gift. It’s a gift we need in a world full of drudgery.

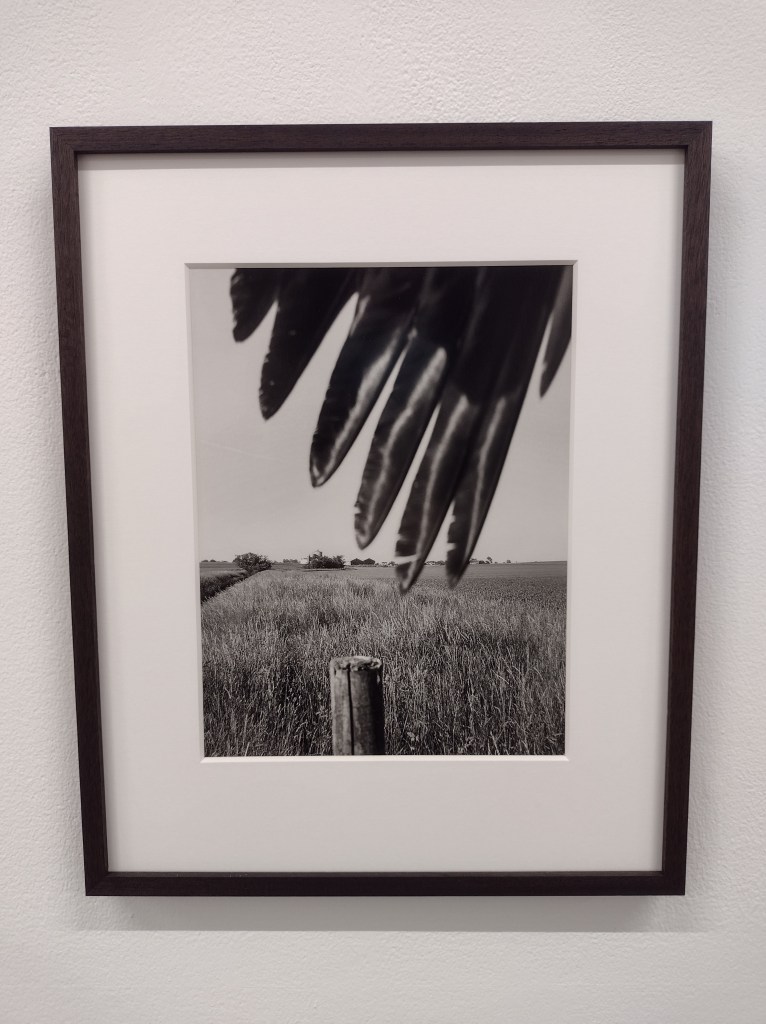

There’s a playfulness and sense of experimentation in Gill’s work that I loved. For his monumental work Talking to Ants, Gill scooped up detritus from the surrounding landscape and embedded it into his camera: stray hair bobbles, broken glasses frames, seed heads, bits of ruler and even insects weave their way into his photos and complicate the scale of the landscapes behind them. These ‘image ingredients’ make for a fascinating display that is utterly mundane but also strangely beautiful. Cable ties have never looked so poetic.

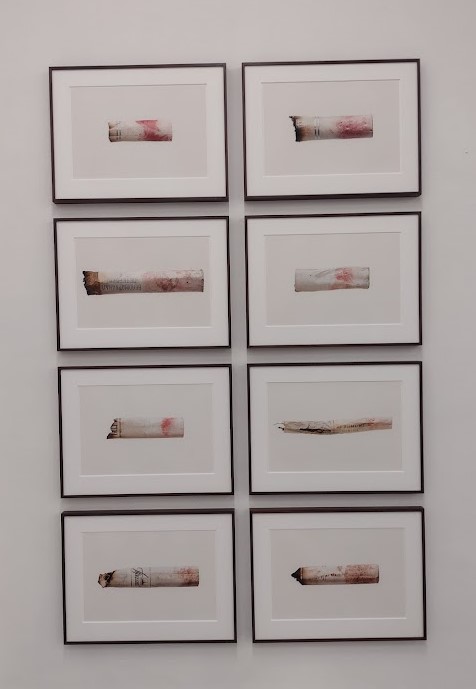

I feel somehow reassured that creative people will be brave enough to do things that others wouldn’t dream of: sticking a camera on a pole and shoving it between iron shafts on railway bridges in order to try and photograph the pigeons that live there (Pigeons, 2012) or collecting lipstick-marked cigarettes from the streets of St Petersburg to compile a series of anonymous portraits for Russian Women Smokers (2002). There’s a courage in this sort of experimentation, one that is drawn from a conviction that an idea is worth exploring, that there’s something special to be found in the documentation of everyday scenarios, no matter how repetitive or odd the process of capturing those scenarios may be.

I wanted to make a study deep within the underside of brick and iron railway bridges where I found the bleak and colourless hidden labyrinth of the pigeon world

Stephen Gill

For his work Pillar (2015-2019), Gill set up a motion-sensor camera on a fence post outside his home in Sweden, and over the years, that camera caught so many wondrous sights, even he was surprised by the variety of birds that visited this strange rural CCTV outpost. There were flypasts from flocks of starlings, contortionist crows and even fearsome looking birds of prey that seem to be posing for the camera. The feeling that underpins Gill’s work is one of trusting the process, a conviction that if you look out the window for long enough, something good will happen.

It’s an attitude that is reflected, emphasised and celebrated in The Artist’s Way, which I have been working through, sometimes diligently, sometimes reluctantly, for eight weeks now. Week Six (when I began writing this blog post) is all about ‘recovering a sense of abundance’ and includes some of my favourite tasks so far, collecting interesting rocks, flowers or leaves, playful reminders of natural beauty and ‘creative consciousness’. I’ve not yet bothered to collect any stones or leaves, but I did see a feather with raindrops on it on a gravel drive, which was so beautiful it stopped me in my tracks. I’m thankful to both Cameron and Gill for helping me to see it.

As December now draws to a close, I find myself reflecting again on my own creative endeavours over the past year. This is my first proper blog post for six or seven months, so perhaps The Artist’s Way is helping me get back into writing at last. It hasn’t been an easy year for anyone, and it doesn’t look like 2022 is about to get a whole lot easier. However, I continue to draw comfort from art and the way it brings interesting, creative and supportive people together. Thank you to everyone who recommended shows, books, articles and exhibitions, who challenged me with creative conundrums, who joined me on Instagram for 20 Mins With and the (recently somewhat elusive) Sunday Spotlight. You’re all gems for reading this far. My wish for 2022 is that we continue to encounter art, and hope, where we least expect it.