The corner of West Sussex where my Dad lives, you are never far from a large country estate. Brown National Trust signs proliferate (Petworth; Uppark), and there are also estates that are still going, that still belong to some of the country’s richest families. You can tell this even by the architecture. In the villages surrounding Midhurst, many of the houses windowframes are painted in a bright saffron yellow, the colour of corn-fed chicken’s egg yolks. To a casual passerby, this might just be a jolly colour scheme collectively chosen by the locals, but in reality they are a territorial marker, showing that they belong to the Cowdray Estate (a 16,000-acre estate owned by Michael Pearson, aka the 4th Viscount Cowdray).

The Viscount’s neighbour is Charles Gordon-Lennox, 11th Duke of Richmond. His estate, Goodwood, is about 10 miles south of Cowdray. He is the owner of the the Goodwood Art Foundation, a beautiful new sculpture park and exhibition space tucked amongst the rolling hills of the South Downs. From 1992-2020, it was the site of the Cass Sculpture Foundation but it has been expanded and reopened. As it’s just a stone’s throw away from my Dad’s, I was keen to get there. Especially when I found out their first headline exhibition is by Rachel Whiteread, an artist I researched as part of my Master’s in 2019.

My first impression is one of taste: everything looks new and clean and swanky. Like it cost a lot. There’s a striking black and silver and asymmetrical building, and for a second, it feels like I’m back at the Louisiana museum on the far reaches of Copenhagen. But the landscape around here is undeniably English: the rolling hills, the ancient woodlands, and the mighty oak trees dotted in the fields. It’s a fascinating, jarring almost, setting for Rachel Whiteread’s work, which has always struck me as unfailingly urban. Her use of concrete is what defines much of her sculpture, with her most famous work, House (1993) filling up an east London townhouse from the inside out, then its cast left behind, standing as a lonely monument to demolition and faded domesticity.

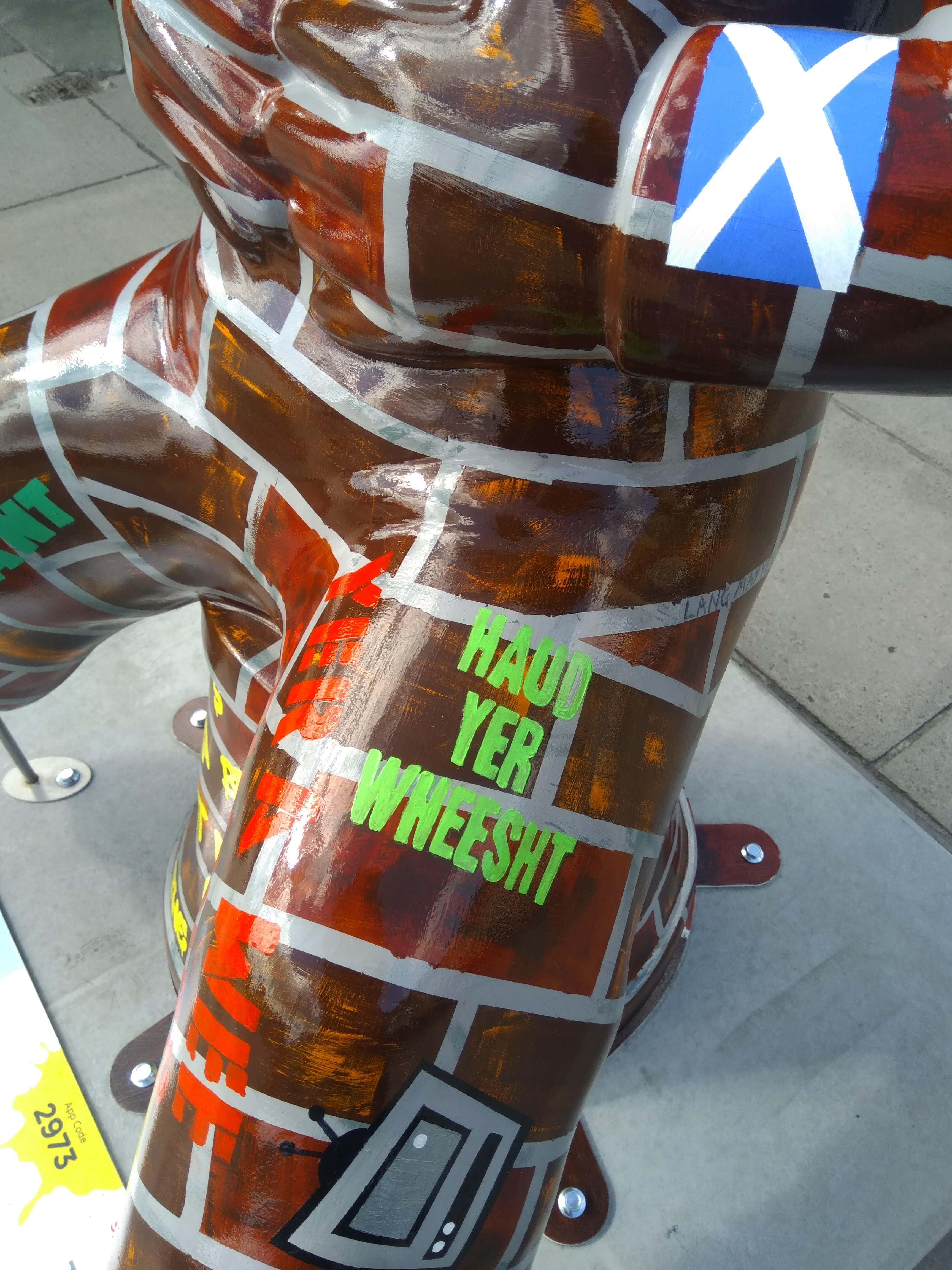

This season, Whiteread is the main focus of the larger gallery, one of two indoor art spaces at the Foundation. In the centre, the space is dominated by her work Doppelgänger (2020-21), a bright white ghost of a tumbledown corrugated iron shack, trees poking through the building’s seams. However, I was drawn to the photos on display, the first substantial showing of her photography. Her photos, like most people’s, were largely taken on her phone and capture landscapes, interesting shapes, everyday encounters with the traces of human presence, or as she says “eccentric features” that interest her. Whiteread views photographs as a form of notetaking, a sentiment which strongly chimes with me. Part of the reason for starting this blog came from a desire to capture those artistic ‘encounters’ that one meets within the city. So in Whiteread’s photos, we see fragments of colour against brown and grey of signs and posts, and the pleasing, satisfying textures of tiles, pictured side by side with dried, fragmented earth. The wall labels tells us the locations for these images: France, Rome, California, Essex, Tuscany.

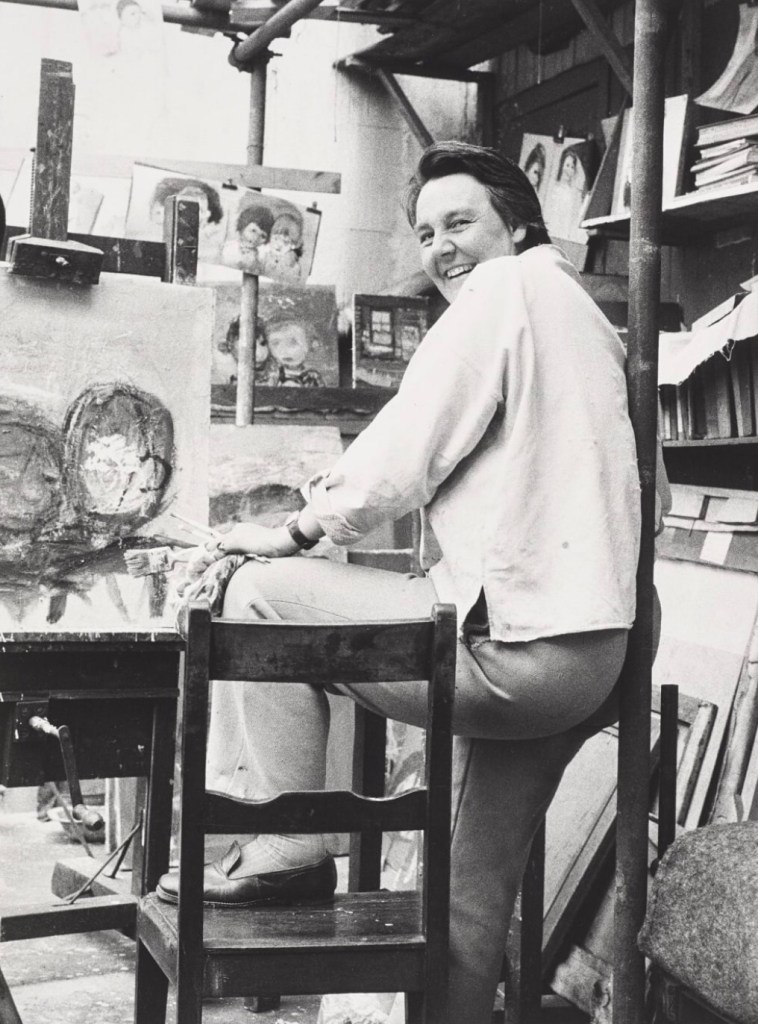

Back outside, my Dad and I strolled around at an easy pace, enjoying the vistas through the woods and occasionally playing a game of “is it an artwork or is it a nicely arranged pile of wood?” The landscape gardener, Dan Pearson, clearly has a nuanced understanding of the playful boundary between them. I enjoyed the exploration of materials and fragility in Veronica Ryan’s Magnolia Blossoms (2025) a circle of fallen petals and buds made from bronze. Rose Wylie’s Pale-Pink Pineapple/Bomb (2025) isn’t my type of thing, but looked pleasantly incongruous in the landscape. Unfortunately, Hélcio Oiticica’s Magic Square #3 (1978) was not yet open for exploration, but I’ll go back.

When we came upon Susan Phillipsz’ work As Many As Will (2015), it took a few moments of listening to the silence (actually the birds and the wind in the trees) before being startled by a lone signing voice, soon joined by others. This beautiful ‘in the round’ song, which Phillipsz sings herself with her soft Scottish accent, about refuge and Robin Hood moved me, but I couldn’t quite say why I had tears in my eyes and a strange catch in my throat. Something about feeling lucky and sad at the same time. How did I get to stroll through this beautiful landscape, stumbling upon art, when there is so much horror unfolding before our very eyes on our phones from morning ‘til night. Why is the world like this.

Whiteread’s unmistakable footprints appear again across the wildflower meadow, her signature concrete casting process back with Down and Up (2024-25), a staircase flung in the wide field like a strange fragment of a disappeared home. The free guide booklet contained an interview with Whiteread, where she refers to this sculptural staircase as “universal memory of a commonplace architectural form”. I cannot think of her work without feeling it is haunted, these casts of buildings capture a ghostly suggestion of a structure that once was and now isn’t there any more. It is no wonder her art is associated with memorials: her Memorial to the 65,000 Austrian Jews who were Murdered in the Shoah in the Judenplatz in Vienna is an unforgettable work. Seeing this staircase then, one cannot help but think of ruined buildings of Gaza, of destruction and war. It is inescapable.

The smaller gallery space housed Amie Siegel’s Bloodlines (2022). I don’t normally engage video art for long, I’m naturally impatient. Here though, in the shade and darkness I was completely captivated by the luxurious interiors of Seigel’s film. Unnarrated, the camera drifts eerily along magnificently decorated hallways and into rooms with ticking clocks, marble pillars and strange taxidermied animal collections. We see an ‘insider’ view of huge stately homes, that are choc-full of artworks. It felt very apt that Bloodlines, which traces the movement of artworks by George Stubbs between private collections and public museums but really explores wealth, history, the legacies of ownership, class, and the strange power dynamics of who owns art and who can look at, and on whose terms that is, felt an important nod to where we were: the art collection of an actual Duke, (because yes, they’re still around), in the middle of a field in England.