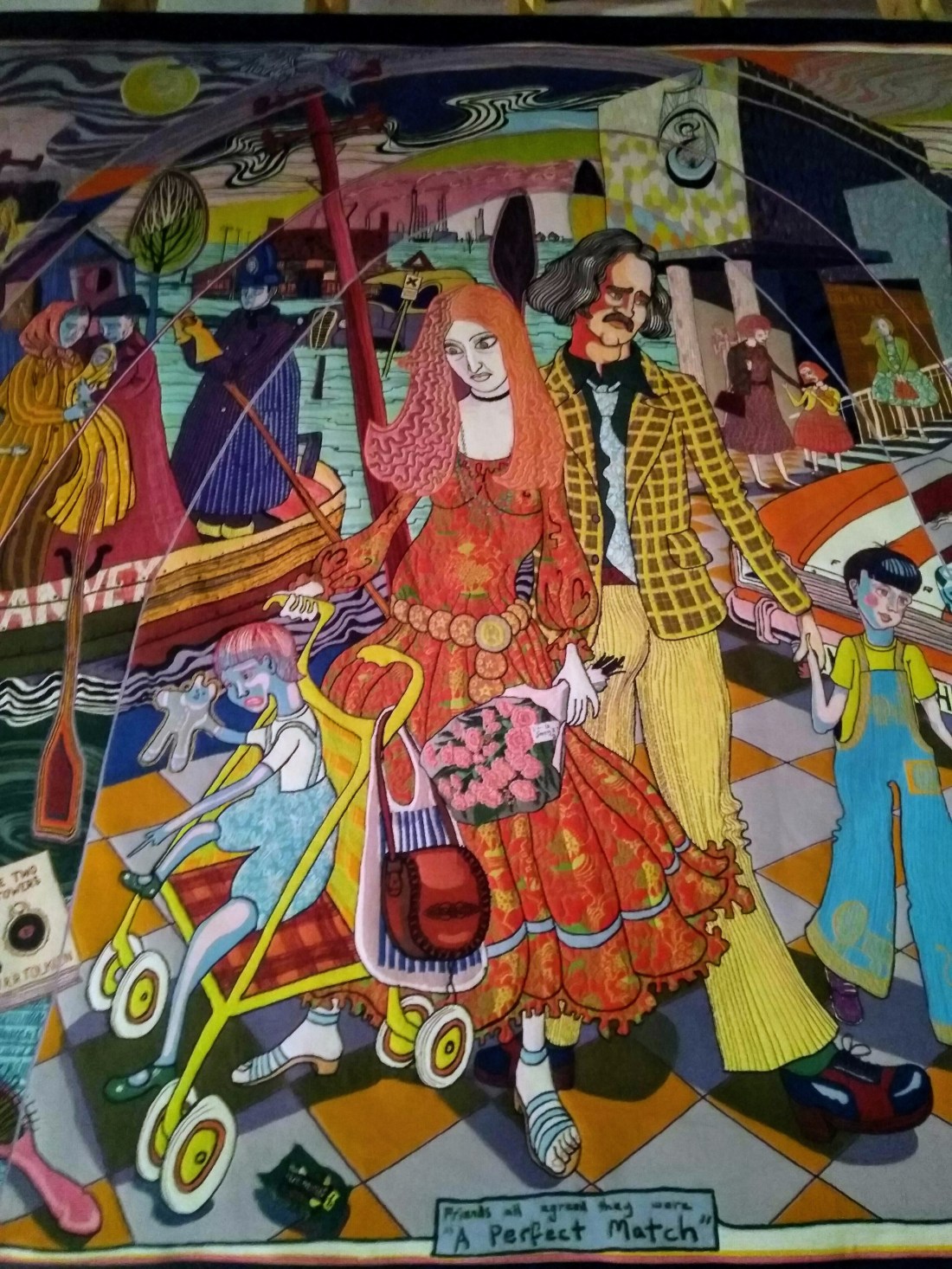

Grayson Perry, with his numerous books, TV documentaries and lectures, is probably one of the few genuinely famous contemporary artists in Britain today. He is perhaps better known for talking about art than for the art he produces, though the bright colours and recurring cast of characters in his ceramics, tapestries and prints, once seen, are not easily forgotten. He is a chronicler, a satirist, a kind of psychedelic William Hogarth of our times, chewing up the world and spitting it back out at us in a way that both gloriously kitsch and raucously ugly.

Perry is fundamentally a storyteller artist. He creates narratives in his artworks which help us to think about the world around us, and our multiple identities as individuals within society. That is what he has done for this show at Dovecot Studios, Julie Cope’s Grand Tour: The Story of a Life by Grayson Perry. The exhibition follows his fictional character Julie through what Perry calls ‘the trails, tribulations, celebrations and mistakes of an average life’, using a series of brightly-coloured Jacquard tapestries.

Don’t be fooled by the bright colours, though. The story behind the works is one that is full of tragedy, examining the mundane reality of life, the pervasive banality even of its most dramatic moments. Alongside the tapestries, The Ballad of Julie Cope, a poem written by Perry bleakly sets the context for Julie’s life. I sometimes find looped audio tracks in exhibition spaces quite distracting, but here, the poem read aloud by Perry in his slight Essex accent gave the tale of Julie Cope, an Essex girl, a kind of timeless authenticity.

The tapestries themselves are immense and impressive. Packed with details, they are a fascinating maze of signs and symbols, clashing colours and patterns for the viewer to decipher. Clever tricks are used that are barely noticeable at first, but make the images all the more convincing, like the shadows used around the feet in the picture above, giving the work a sense of depth and the cartoon-esque characters more solidity.

As with much of Grayson Perry’s work, class is the central theme underlying the show, and his observations about life in modern Britain are as bittersweet and tinged with nostalgia as they are acerbic. The tapestries, when they are not on tour, usually decorate another of Perry’s fascinating projects, A House For Essex, a whacky Wendy house construction which is part folly, part shrine, to Julie Cope. Seen divorced from this context, in the exhibition space, I think the works have probably lost some of their whimsical quality, and we are left with a documentation of the sad predictability of life. For me, the overriding feeling of the exhibition was not uplifting, but in that way, Perry, the Bard, creates a perfect mirror of the country in turmoil around us.