Yesterday ArtAngel ran a live Q&A with artist and director Steve McQueen, following their most recent collaboration for his vast work, Year 3. For this artwork, McQueen arranged for 76,146 kids, from 3,128 Year 3 classes (ages 7–8) to be photographed in the timeless, traditional, and I would even say iconic format of the class photo. It’s something most of us can relate to. Bodies arranged in rows, taller kids standing, some sitting on plastic chairs or old wooden gym benches, and others cross-legged on the floor. What has emerged is a rich tapestry, a beautiful, huge patchwork quilt of thousands of photographs that document the present and, as McQueen emphasised in the talk, the future of London. What an incredible concept for a piece of art. I’ve heard it described as a giant portrait. But it feels far more dynamic, participatory and meaningful than that word implies.

I knew that the work was being exhibited at Tate Britain (I was due to visit in April, and am gutted that now I’m unlikely to see it at all), but from photos the installation looks impressive. The messy brightness of 1,504 schools packed into the grandiose space of the Duveen Galleries would always create a delicious juxtaposition. I hadn’t realised that for the ArtAngel side of the work, some 600 of the photos were created into billboards, situated across all 33 London boroughs, in November 2019. An ephemeral facet of a monumental artwork. It’s the stuff Encounters Art was made to write about – my only regret is to not have seen and documented them myself. In some ways that’s the beauty of these pop up artworks though. They aren’t supposed to be sought out, they mix and mingle with the everyday and you don’t know it’s there until you stumble upon it. If you did see a billboard in London back in November then I would love to hear your thoughts – leave a comment or DM me @encounters_art.

Subverting a space that is usually used for adverts by filling it with a school photograph which is simultaneously strange (because we don’t know these children) and familiar (because we’ve all been children) is such a strong, engaging idea. One of the best moments I’ve come across by searching online for #year3project is a BT advert on Camden Road announcing “Technology will save us”. It is a timelapse video of BT’s billboard being surmounted with a photo of smiling kids in bright red cardigans and summer dresses in an old school hall. Here the children aren’t being prepped and presented as the consumers of the future. They are the future. They will save us. (Though I suppose ironically I owe my thanks to technology for preserving this moment for me to find months later.)

I love seeing these images interwoven into the London landscape. In tube stations, framed by carriage windows, this array of smiling young faces must have cheered up and intrigued countless commuters. Even in the gallery display, away from the urban fabric, it feels like a very London-based artwork, because it celebrates the city’s amazing diversity. McQueen chose Year 3 because for him, that is the moment we start to gain perception of our identities. Our classroom becomes a window on society and a crucible of the nuances of race, class, privilege and opportunity, all of which are explored in the work.

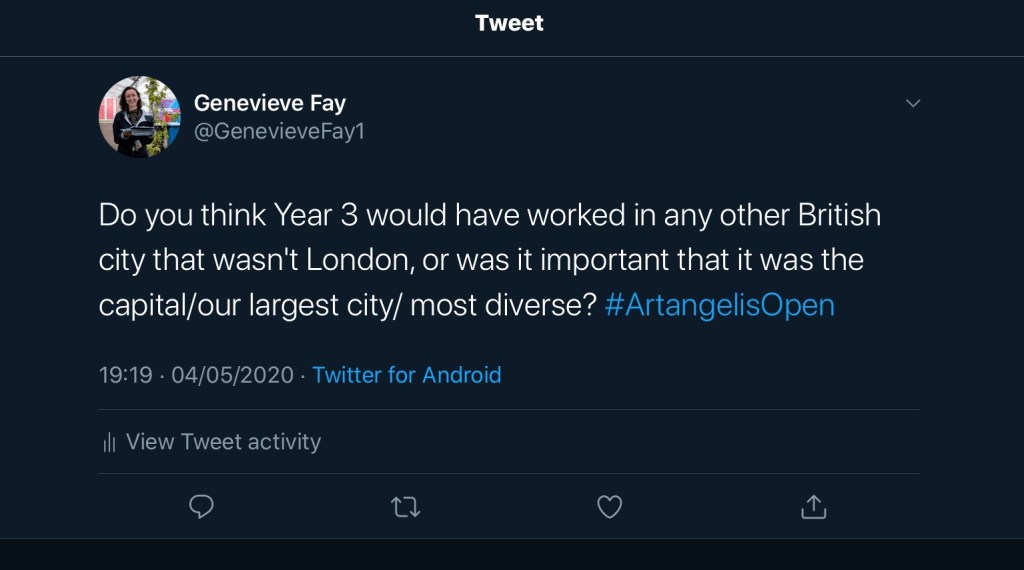

I found the London aspect particularly intriguing so I decided to ask a question using the hashtag #artangelisopen and I couldn’t believe it when it was picked for McQueen to answer. I was so excited, cheering and jumping up and down that I almost forgot to listen to his response. He said that for him, London was the clear choice, but it didn’t have to be limited to that – it could be carried out anywhere – and he seemed to be encouraging people to take up the project and move it on elsewhere. I would love to see that, particularly somewhere like Nottinghamshire (where I grew up) where there are rural and urban childhoods playing out. I wonder if it would click in the same way the original project does.

Listening to McQueen, the work was also understandably rooted in London because that was his experience – despite its scale, there is a highly personal context to the artwork which draws on his own boyhood engagement with art: a primary school outing to Tate Britain was the start of his journey. But it’s also about visibility. According to TIME magazine, Steve McQueen is one of the 100 most influential people in the world. For Twelve Years A Slave he won an Academy Award for Best Picture, and became the first black filmmaker to do so.

By creating this work, displayed in the gallery he visited as a child, he has come full circle. What an amazing thing, to provide an opportunity for the children in Year 3 be able to visit that same space, and see themselves, and others who look like them, on the walls. It fills me with hope that the project will be the spark that ignites countless artistic explorations and adventures. I can’t wait to see what they create when they’re fully grown.