There’s so much packed into this exhibition at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, which connects radically different works of art by artists as diverse as Pietro da Cortona (Italian Baroque painter and architect, 1596-1669) and Linder (British radical feminist artist, b.1954) it’s difficult to know where to begin.

The exhibition is a chronological survey of just about everything connected to the act of cutting one thing and sticking/stitching it on to another, including the digital techniques used today by brilliant artists like Cold War Steve. So there’s a lot to get through.

It might sound as a though the whole concept is a bit broad (it’s true that the exhibition has so many works it almost falls into the ‘overwhelming’ category), but in the very act of broadening out the understanding of collage as art, the show opens up the narrative possibilities around the medium. By including works by amateur and anonymous artists, we see the informal side of collage, which became hugely popular in the nineteenth century, particularly among women. I’m glad of that because it exposes some of the many weird and wonderful constructions that resulted from the pastime of sticking one thing to another, one of my favourites being this monstrously ugly baby from 1890.

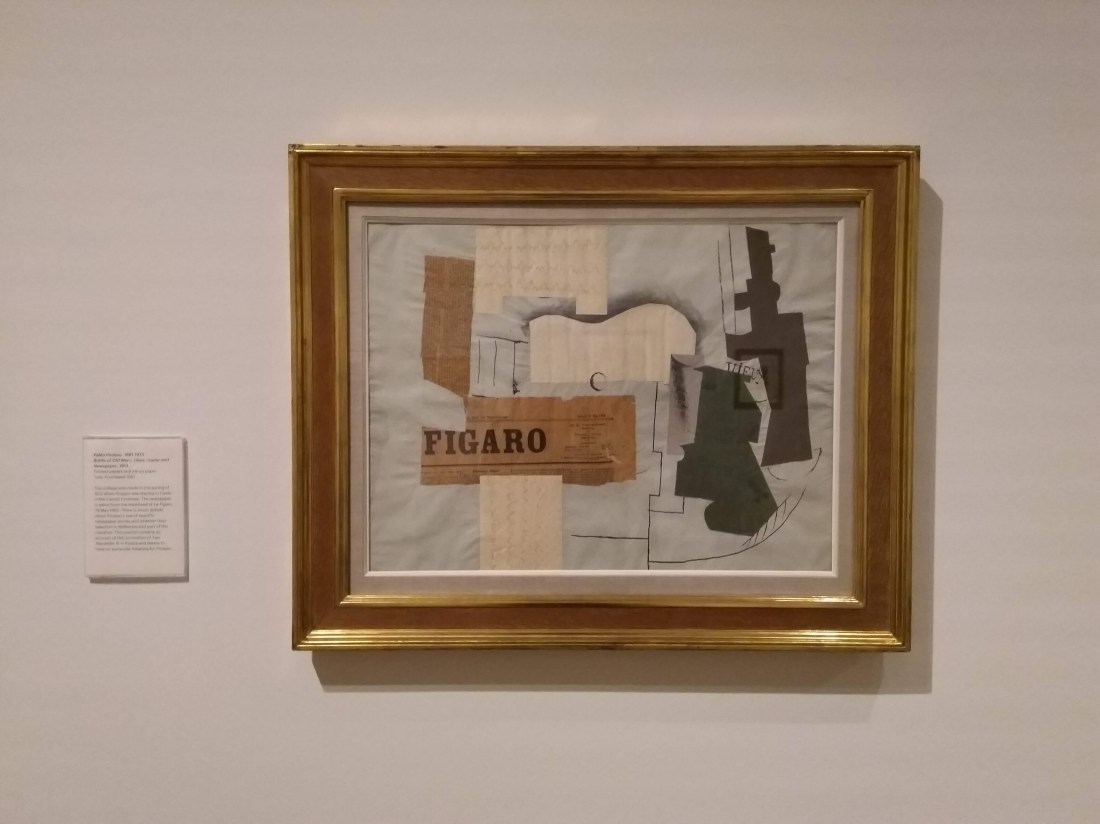

By placing objects like this one alongside Picasso’s Old Marc, Glass, Guitar and Newspaper (1913), the exhibition stressed some of the continuities of collage throughout the centuries. Yet though the wall text explained how the meanings of collage changed in the twentieth century, I still feel that more could have been made of how utterly radical it was when avant garde artists started to incorporate fragments of newspaper and other ephemera on to the canvas. It was a gesture that intended to break the mould and redefine painting altogether, which had huge repercussions on what later constituted art. It was for this reason that collage went on to be one of the go-to visual languages of satire, protest and activism.

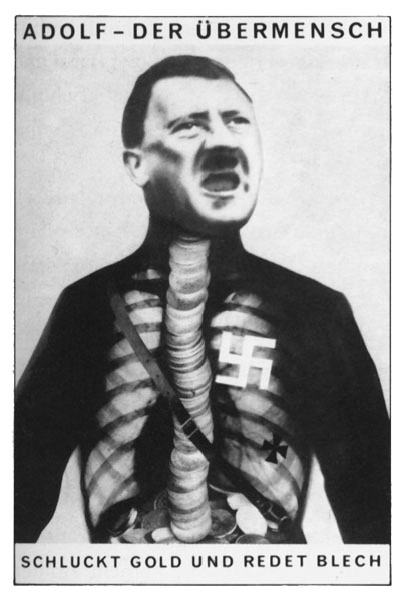

For me, the political artworks were some of the best in the show. John Heartfield’s series of satirical photomontages for the left-wing German publication AIZ really fascinated me. One, depicting a Hitler with coins for a skeleton alongside the caption “Adolf the Superman: swallows gold and spouts rubbish” (1932) felt particularly apt to our current political climate. I just wish the series was placed somewhere more prominent, rather than in a walkway. The exhibition has so much to say, but there wasn’t enough space to say it. Better to cut down on the numbers of works and give ones like this the position they deserve.

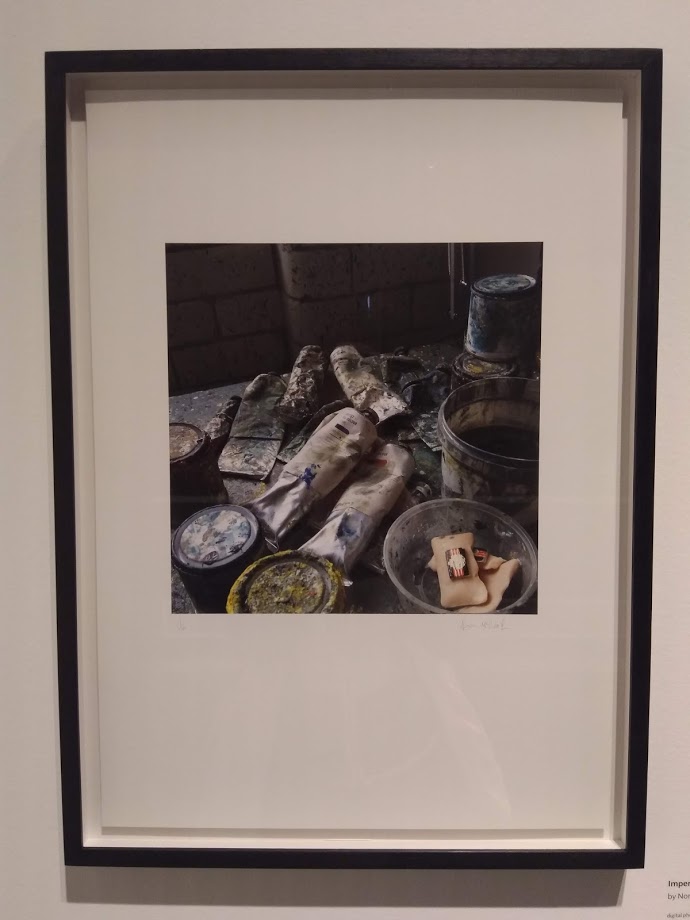

It seems that with works in collage, there’s a strong urge towards the uncanny, things that disturb and make the viewer take a second look. That was true of the works exploring the body by feminist artists of the 1960s and 70s, in one of the best rooms of the exhibition. I hadn’t heard of Annegret Soltau (b.1946) before, and her works made with black thread suturing together different photographs of her naked body were really striking.

There are so many fascinating things to see at this exhibition and it throws a light on some of the challenges of dealing with such a broad theme. It is said too often, Qbut there really is something for everyone here, and I would really recommend you go and see it before it closes on 27 October.