It only feels like yesterday that I put together my five to see at 2023’s iteration of Edinburgh Art Festival. And we’re already one week in! The Festival officially finishes on August 25th, but don’t fret. Many of the shows carry on beyond festival season.

EAF is 20 years old this year and there really is something for everyone. So if you’re searching for something different to do this weekend, with a bit of space from the Fringe crowds, here are my suggestions.

Ibrahim Mahama: Songs about Roses

Fruitmarket Gallery until 6th October

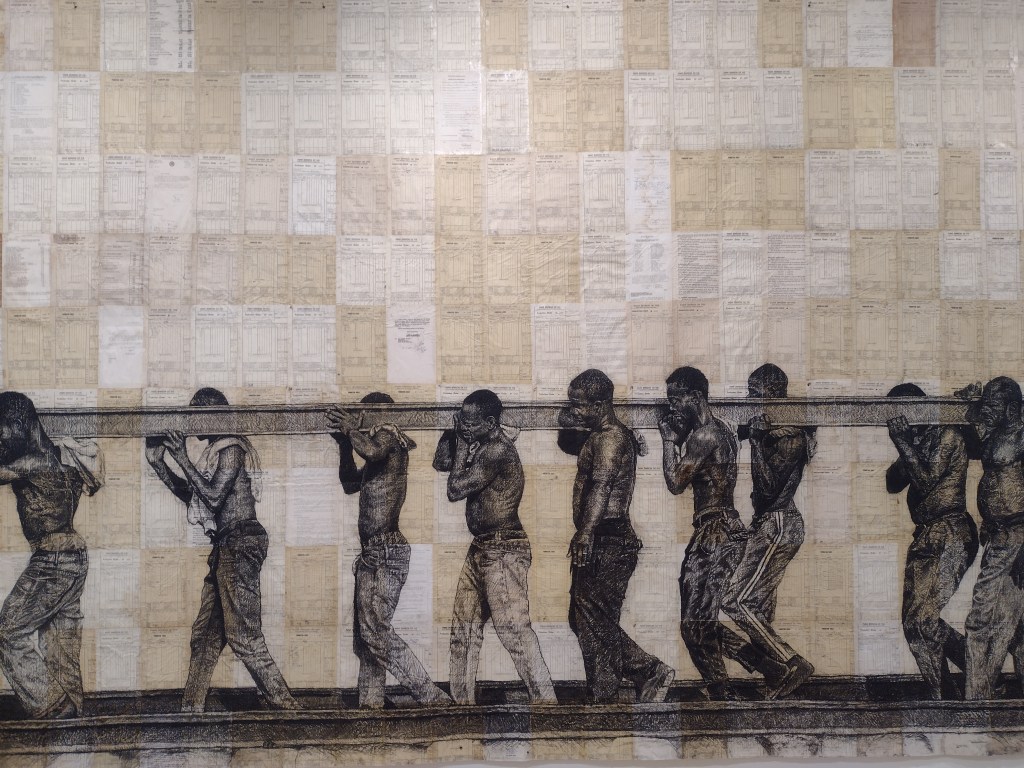

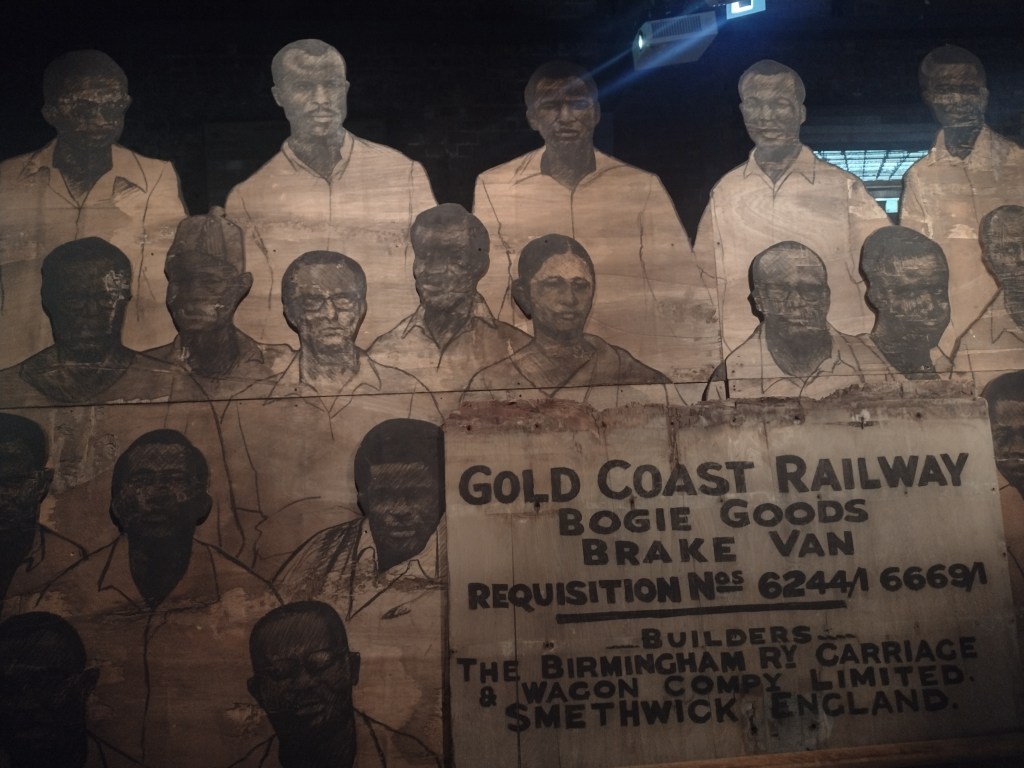

When talking to odious people about colonialism one of the things that might be brought up is how colonisers implemented infrastructure – roads and railways – to the country that enabled it to advance. Songs about Roses explores the reality: these infrastructures were just a mechanism for extracting goods out of that land to make profit for the colonisers (pillaging). Mahama has collected huge pieces of a now defunct railway that was built by the British in 1923 to transport gold, minerals and cocoa around the area of Ghana that was then known as the Gold Coast. He has subverted and reframed these materials and given them new meaning in the process. In a video played on the ground floor, we see drone footage of these immense, rusted train carriages being transported across the Ghanaian landscape, like a funerary procession. Archival documents show the administrative nuts and bolts of empire building, that have now become the canvas for portraits and line drawings.

Delving further into archival material, Mahama has gathered group photographs of railway staff, which were taken pre-independence at railway workers’ retirement parties and company events. These are now rendered lifesize in charcoal and mounted on old railway tracks. The ghosts of colonial infrastructure have now returned to the Fruitmarket Gallery warehouse space: the place has become a monument to the railway workers, members of strong unions that played a key role in Ghanian independece and its immediate aftermath. It’s a dark room, thick with dust and the smells of industry. Perched as it is above Waverley station, I couldn’t help but think of Jamaican philosopher and academic Stuart Hall’s words on empires: ‘we are here because you were there’. These legacies are the ghosts of history and they have come home to roost.

Yet it’s not an exhibition that is about the story of historic exploitation alone. It’s also about Ghana’s future. The collaborative nature of Mahama’s practice is a source of hope: he sells his work in Europe and the USA and funds art and education institutions and projects in Ghana with the profits. Many of the works in the exhibition have links to audio of Muhama discussing the process of creating the works and exploring the ideas that inspired them – definitely worth a listen when you visit.

Renèe Helèna Browne: Sanctus!

City Art Centre until 25th August

I was lucky enough to meet artist Renèe Helèna Browne before seeing this piece, who explained how, though the surface story is about rally car driving, races and culture in Ireland, creating Sanctus! was really a mechanism to get to know their mother better. Browne discussed how, when thinking about their mother’s life, it was dominated by two systems: the catholic church which presided over her childhood, and the system of motherhood and raising children which followed. Both of these are explored in the work, but slowly, tentatively. The main piece is a film, lasting about 15 mins, obscured behind a red leather curtain (the red is a nod to the colour of Browne’s uncle’s rally car). As the viewer sits in the darkness we are confronted with the sounds of cars revving their engines. We see a distorted view of leaves and branches buffeted by the wind – reflections in the shiny paintwork of a vehicle.

What emerges is an intimate but simultaneously distant picture of the artist’s mother. At work at the farm. At home. Snippets of conversation where artist and mother discuss family deaths, the afterlife, faith and meaning. Their conversations seemingly evolve side by side but never quite join together. An intimate portrait of memory surfaces: the teenage child meticulously dyeing the mother’s hair and eyebrows. All the while the film explores the hyper-masculine space of rally driving. A little boy in full rally gear eagerly awaits the cars at the side of the road, poses for family photos with his father, uncles, cousins. Teenage boys drive cars in mesmeric circles like a dance, where they edge ever closer until you feel sure that one of them will collide (I think it’s called adjacent diffing). Meanwhile, we see the artist’s view from the sidelines. It feels as though this rally driving world is a source of nostalgia, a means of connection hovering close but always just out of reach. Fascinating and multilayered: I hope to go again to see the things I missed the first time. I also need to get some photos!

Home: Ukrainian Photography, UK Worlds

Stills Centre for Photography until 5th October

I am always drawn to the shows that Stills puts on and this one is no exception. There’s much talk about how now that everyone has access to good quality cameras via their smartphones, everyone’s a photographer. But when you go into a place like Stills you realise there is a still a difference. During the hype and excitement of the Fringe, it seems like the last thing you might want to do is look at photographs documenting the brutal realities of war. But the way this small but powerful show is put together makes it utterly necessary. We see a snapshots of clothes and possessions that refugees have left behind on a beach. There are insights too from Ukrainian life from the very end of the Soviet Era: in Passport (1995) photographer Alexander Chekmenev visiting the elderly at home to take passport photos and exposing the brutal reality of their living conditions. There’s an apartment block which looks like a doll’s house because the front of it has come clean off.

In the series that captured my attention the most, Ukrainian Roads (2022) by Andrii Ravhynskyi, we see roadsigns that have been obscured by bin liners, plastic bags, the mileage between towns and village names daubed with black paint: all attempts by local Ukrainian citizens to confuse and disorientate the Russian army whose GPS was patchy at the beginning of the war. Something so simple as a road sign, that looks so familiar, conflated with what has now become familiar because they are synonyms of war: Kharkiv, Kyiv, Simferopol. These images are deeply unsettling but demand to be seen.

Platform24: Early Career Artist Award

City Art Centre until 25th August

I always enjoy seeing what the EAF Platform artists are up to. Now in its 10th year, the platform programme is a group show for emerging artists, and they have taken over a floor of the City Art Centre with this year’s presentation. The artists are Alaya Ang, Edward Gwyn Jones, Tamara MacArthur and Kialy Tihngang, who were asked to respond directly to the themes of the 2024 programme: intimacy, material memory, protest and persecution. My particular favourite was Gwyn Jones’ multi channel video piece Pillory, Pillocks!, where we see muck, slime, food residue and all manner of unknown substances flying at the face of a person looking back at us. He flinches, we flinch, and each time is saved by the presence of a clear screen. The artist says that it’s a response to historic shaming of people (think the stocks, rotten vegetables), humiliation and entertainment. It reminded me how as children we used to watch “get your own back” willing parents to be covered in slime. While you pity the man in the video, part of you wills for the protective screen to disappear.

I promise I will add some pictures to this section when I revisit!

El Anatsui: Scottish Mission Book Depot Keta

Talbot Rice Gallery until 29th September

It feels so right that El Anatsui’s exhibition overlaps with Ibrahim Mahama’s at the Fruitmarket. Both artists are concerned with materiality, the legacies of history, colonialism, consumerism and they both work on a vast scale. I love El Anatsui’s work because it can be taken in on so many levels. You begin seeing the work from afar, dwarfed by it (recently, these huge scale works have adorned the side of the Royal Academy and the Turbine Hall in the Tate Modern). As you approach, it’s like zooming in to see the pixels in a photograph, each element emerges as unique and distinctive. These huge ‘tapestries’ may look like woven Kente cloth, but slowly reveal themselves as thousands of pieces of reclaimed aluminium bottle tops, from Ghana and Nigeria’s liquor bottling industries.

This exhibition is the largest examination of El Anatsui’s work staged in the UK, and spans five decades of his career. The crowning glory is the beautiful and huge outdoor installation TSIATSIA – Searching for Connection (2013) which dominates the Old College courtyard, draped over the Georgian architecture like some shining shroud. Yet it’s also a treat to see smaller works which I wasn’t so familiar with: works on paper, and carved wooden reliefs. I would love to see these two giants of Ghanaian art in conversation. Or, at least responding to the other’s exhibitions. Come on Fruitmarket and Talbot Rice, make it happen?

There are still shows I haven’t managed to see yet, so what I’m looking forward to exploring next are:

- Más Arte Más Acción: Around a Tree at the Royal Botanic Gardens

- Before and After Coal at the National Portrait Gallery

- Ade Adesina: Intersection at Edinburgh Printmakers

- Matthew Hyndman: Updended at Bard

I would love to hear what others have been enjoying at EAF this year. Let me know in the comments!