We visited on a cold, bright day fringed with snow. Humlebæk is an unassuming town a short train ride away from Copenhagen, and I imagine it’s mainly home to commuters. Yet it also boasts one of the great collections of art from 1945 onwards, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art.

Louisiana is one of those museums that just feels well done. It’s clearly immensely popular. It’s classy, sophisticated, cared for, and it feels rich. Turns out it is a private, state-recognised museum, which means around 15% of its revenue is from the Danish public sector, with the rest made up by commercial activity and sponsorships. Louisiana was founded in 1958 by Knud W. Jensen, who wanted more Danes to access contemporary art. Think the Peggy Guggenheim Collection meets Jupiter Artland. Like a smaller, more accessible Tate Modern.

The place buzzed with dynamic energy. Perhaps this is because, although the collection is large, you will not find a decade by decade chronological survey of art from 1945 to 2025 here. The display policy is centred around a programme of rotating, thematic exhibitions, interspersed with a few of their collection highlights which are on near-permanent display. For our visit, the main exhibition was OCEAN (October 2024 – April 2025), exploring humanity’s complex and fraught relationship with the sea.

It’s apt, because Louisiana sits right on the edge of the Øresund, the strait between Denmark and Sweden which is one of the busiest waterways in the world. On 2nd January however, it was an empty deep blue canvas. Some of the works that resonated the most with me in the exhibition weren’t contemporary at all: there were beautiful antique sculptures which showed the sea as both protector and destroyer. The parts that had been submerged in the sand were uncannily smooth, while the exposed sections had been eaten away by sea creatures, and eroded by the water itself.

Close by, El Anatsui’s Akua’s Surviving Children (1996) was formed of pieces of driftwood and iron found 20 kms north of Louisiana when the artist was visiting Denmark. It represents a group of enslaved people returning from the sea, and was initially assembled at a local arms factory that had provided weapons utilised in the Danish slave trade in Ghana, in the 18th and 19th centuries. Positioned directly behind it was Kara Walker’s The Rift of the Medusa (2017), (after Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa, 1819), bringing the violence of both the sea and of humans into sharp relief.

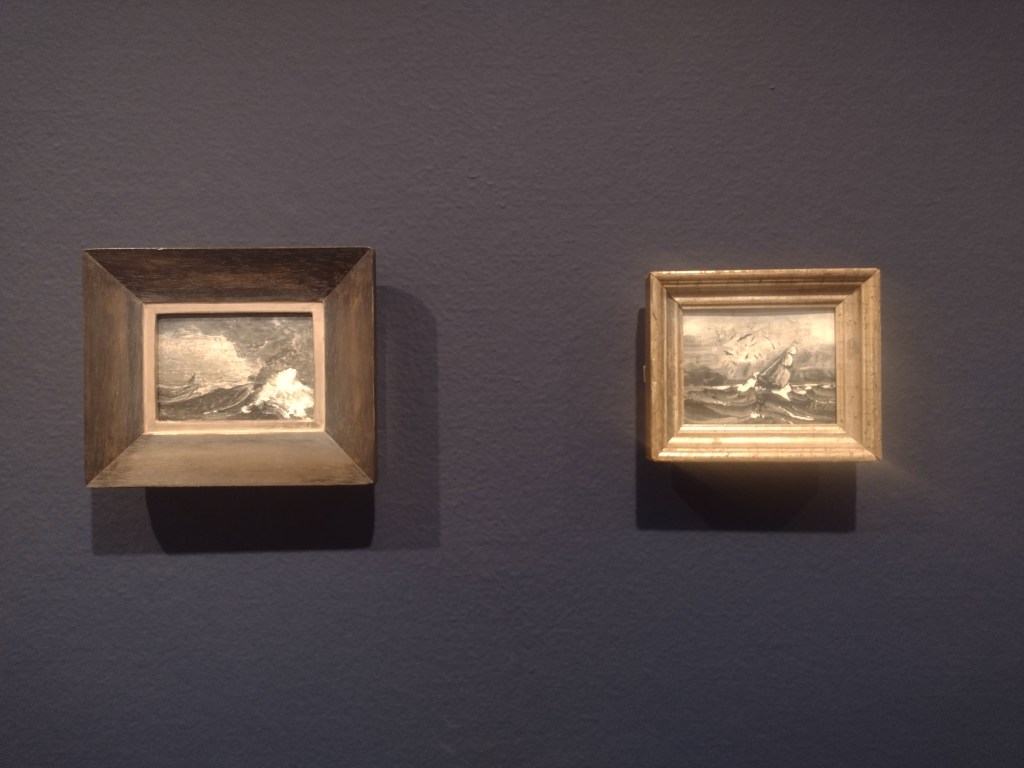

There were paintings, Japanese woodcuts, video art, sculptures. Tiny paintings of the wild sea by Peder Balke met large scale canvases by Anselm Kiefer. I was briefly transported back to Britain via Susan Hiller’s Rough Seas series, where the artist has collected hundreds of vintage postcards of the sea crashing into picturesque towns around Britain’s shorelines: each one depicting the sublime power of the sea in miniature. Sensitive, thoughtful curation meant this vast range of works were able to function in dialogue, opening up new ways of thinking, seeing and even feeling about the sea in all its complexity.

The quality of the Louisiana collection is extraordinary. If you pick any famous artist you can think of from the past 80 years, they probably own one of their works. When we arrived, we made a beeline for one of the few year-round installation artworks, Gleaming Lights of the Souls (2008) by Yayoi Kusama. Having failed miserably to get to the Yayoi Kusama Infinity Rooms that were installed for three years at Tate Modern, it was amazing to have only a short queue to see this mesmerising work. Surrounded by mirrors and water, it is easy to see why Kusama’s work is so popular in this era which prizes immersive experiences more highly than any other mode of interaction with art. Other highlights elsewhere in the museum included seeing Louise Bourgeois’ gigantic Spider Couple (2003) installed by a giant floor-to-ceiling window, their spindly legs echoing the tangle of branches outside.

What changes a ‘good’ museum or gallery to a ‘great’ one? Much though I love Scotland’s museums, it is clear to me that even though Denmark and Scotland have a similar size of population, I can’t currently see a way that a museum of Louisiana’s scope, scale or calibre could ever be supported here. It has entire wing for kids, a sculpture park, runs an annual literature festival, hosts its own broadcasting channel which creates new educational content every week, and is open as a music and events space every Thursday and Friday until 10pm. This is one of my chief frustrations with galleries in the UK. You have to be freelance, retired or a student to go there during the week – places open at 10am and close at 5pm so if you’re working, sorry, you have to go at the weekend with everyone else. This seems to be such a missed opportunity to me.

Starting the year visiting such a wonderful museum has given me renewed ambition to try and see more art this year and write about it. For my next post, I’m planning on focusing on 2025’s must-see events and exhibitions much closer to home. Watch this space!