There’s a new, free exhibition in town, at the Botanics. Ever a beautiful place to relieve your Covid-19 cabin fever, to feel the peace of looking at plants and be made to feel small by impossibly tall trees, now you can supplement it with a visit to Florilegium: A Gathering of Flowers. The first exhibition since the RBGE started its Climate House initiative, the exhibition marries what seem to be two very different ways of looking at flowers.

The first is factual, scientific, research-based. Packed into the first room are depictions of flowers from the Garden’s collections, submitted by botanical illustrators from around the world. I love their precision, the sense that these drawings have been set to view in HD. Glancing at these densely stacked images, their uniform wooden frames fitting perfectly with the olive green of the wall, I’m convinced there would be enough detail here alone to make an entire exhibition. Enhanced by the ikebana style floral displays, it’s what visitors might expect, might hope to see. It’s beautiful, classy, and it’s about flowers. Tick.

Up the stairs, we’re taken into a somewhat different realm by four contemporary artists, Wendy McMurdo, Lee Mingwei, Annalee Davis and Lyndsay Mann. While the immensely skilled botanical illustrators are concerned with depicting the flower exactly, and in some cases, the pollinators too, the artists upstairs are more concerned with what we cannot see. The emotions and meanings we as humans attach to plants, their embroilment in our colonial past, and the metaphor of life and death a flower provides so effortlessly, are all explored here.

Wendy McMurdo’s photographs from the Indeterminate Objects series from 2019 use gaming software to collapse the blooming/withering lifecycle of a single flower in one vase, an eye-catching narrative that makes you look twice. Her Night Garden series (2020), reflects on how her mother’s ill health and recent death was combined and synchronised with blossoming of a large, mystery, tropical-looking plant in her suburban garden. I loved the uncanny photo of seeds resting in the palm of her hand, which looked to me like the hand itself was punctured, decaying: a wound between the states of hurt and healing.

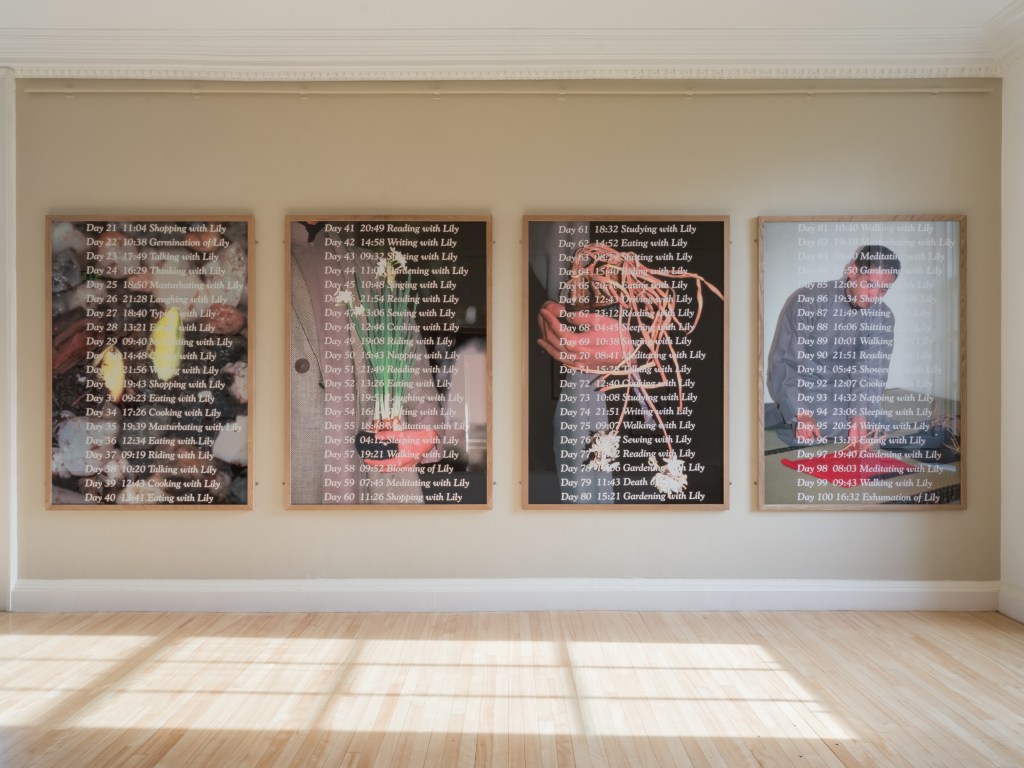

There’s a pleasant chiming here with the work 100 Days with Lily by Lee Mingwei, which documents a performance created back in 1995. His grandmother died, and in mourning he lived with this plant for 100 days, carrying it everywhere. He projects his own grief on to lifecycle of this plant, but the presence of the banal activities of daily life (Eating with Lily, Sleeping with Lily, Shitting with Lily) overwrite and undermine this strange, solemn ritual. For Florilegium, Mingwei has planned a new work called Invitation for Dawn, where opera singers will perform directly to the recipient via live video call. It sounds weird, experimental and intimate, but in a great way. You can participate between 16 November and 11 December, email creativeprogrammes@rbge.co.uk for more details on how to get your ‘gift of song’.

The work of both Annalee Davis and Lyndsay Mann anchors the exhibition in something deeper, bringing the role of the Botanic Garden, the collection of plants, the colonial ecosystem at the heart of RBGE’s existence, into view. Annalee Davis is a Barbadian artist whose studio is situated on what used to be a sugar plantation. Her practice investigates the history of that land, examining the power structures that have been tilled into the soil. Here, her series As If the Entanglements of Our Lives Did Not Matter (2019-20), is casually pinned up on the wall, unframed, unglazed. It immediately felt visceral and direct, denying the formality, poise and stiffness of Inverleith House. Pink, flesh-like depictions of messy clumps of roots are daubed over old payment ledgers from the plantation, which are intriguing, loaded documents in their own right. In a haunting portrait, she places two of her ancestors side by side, who though blood relatives, would have never lived together in reality, separated as they are by race and class.

Davis’ art works in dialogue with Lyndsay Mann’s A Desire for Organic Order (2016), a mesmerising film of 55 minutes which explores the RBGE’s Herbarium, where species of preserved plants are kept for study and research. Although most visitors won’t have time watch the film from start to finish, it’s a fascinating piece, which shines a light on the strangeness of it all: the meticulously categorised, catalogued, classified plants, sitting in row upon row of filing cabinets and box files, the collection expanding over the centuries as new species are found and brought to the RBGE, their final resting place.

The violence surrounding these collections is examined at a distance, with the narrator’s voice dispassionately implying but never quite explaining what we know now, that far more care was given to these foreign plants than to the humans who lived alongside them. If you do have the chance to sit here a while, I’m sure it will make you see the exhibition, and the whole RBGE endeavour, in a slightly different light. You may not think you need this part of your world to be challenged, that you just want to enjoy the Botanics and not think too much about the difficult history and context. But it’s the ability of artists to show things you thought you knew in a new way, that is what makes them so vital to how we think about our past, present and future. That’s why we need the upper floor of the exhibition. We can’t just have a “gathering of flowers”, we need someone to tell us what they mean.