After months of closed doors and darkened rooms, museums and galleries are set to begin opening in Scotland from Monday 26 April. Unsurprisingly, I’m excited about the prospect of returning to experiencing art ‘in the flesh’, though lockdown has proven that art can be found everywhere and anywhere, and isn’t confined to the walls of a hushed gallery space.

Over the past year, I’ve had to be more imaginative about what to look at and write about: seeking out artists to highlight each week on Instagram, exploring virtual viewing rooms and reading more art criticism. This unwanted pause on what had seemed a never-ending cycle of exhibitions has, I hope, made the blog less of a diary of exhibition reviews, and more a set of broad suggestions of how we can engage with art.

The more I think about it, the more I realise we’ll have to reacquaint ourselves with how to look at art in person, as the world around us becomes available again in all its glory. How will we prioritise our time? Can we pace ourselves? Will we be overwhelmed, underwhelmed, or just ‘whelmed’? Will our stamina for standing and wandering around galleries be a shadow of its former self?

Contrary to what some might suggest, Edinburgh is alive and buzzing with art all year, so here’s a round-up of some things I’m most looking forward to visiting in person this spring and summer.

Jonathan Owen at Ingleby Gallery: 29 May-17 July

Regular readers will know that I love the Old Masters. That’s where my art journey started (as a child I loved The National Gallery card game). But I also love it when contemporary artists reinterpret traditional forms to say something new e.g. Meekyoung Shin’s slowly eroding soap sculpture of the Duke of Cumberland in Cavendish Square. Jonathan Owen is such an artist. His work uses erasure and interventions to alter found materials, including marble statues. This show at Ingleby Gallery, one of my favourite places to see art in Edinburgh, will feature these altered statues, and will also include the unveiling of a new life-size work about empire and exploitation. I’m sure this exhibition will go straight into the heart of the monument debate and I can’t wait to see these sculptural works in 3D. For me, sculpture is something you have to see in person. The screen just doesn’t cut it.

nineteenth century marble figure with further carving

A very interesting rehang at the Scottish National Gallery: Open Thursday-Saturday from 6 May

When I was studying art history at ECA, we were incredibly lucky to get to visit the Scottish National Gallery before opening hours. I remember asking our host, Frances Fowle, Senior Curator of French Art, why some of the most famous paintings are kind of… hard to find in the Gallery. While some people love the fact that you go up a narrow set of stairs and suddenly you’re surprised to be in the company of Van Gogh’s Olive Trees, Monet’s Haystacks and Gaugin’s Vision of the Sermon, apparently lots of folk agreed that they seemed needlessly buried. The latest Friends newsletter explains:

You spoke, we listened. For the re-opening of the Scottish National Gallery we have moved seven of the much-requested Post-Impressionist paintings to a display on the ground floor.

While I doubt this will be a permanent change (the rooms upstairs are probably a much better scale for these works), it will be really wonderful to see these incredible paintings placed front and centre, and I’m fascinated to see how the team at the Galleries will take on this re-hang.

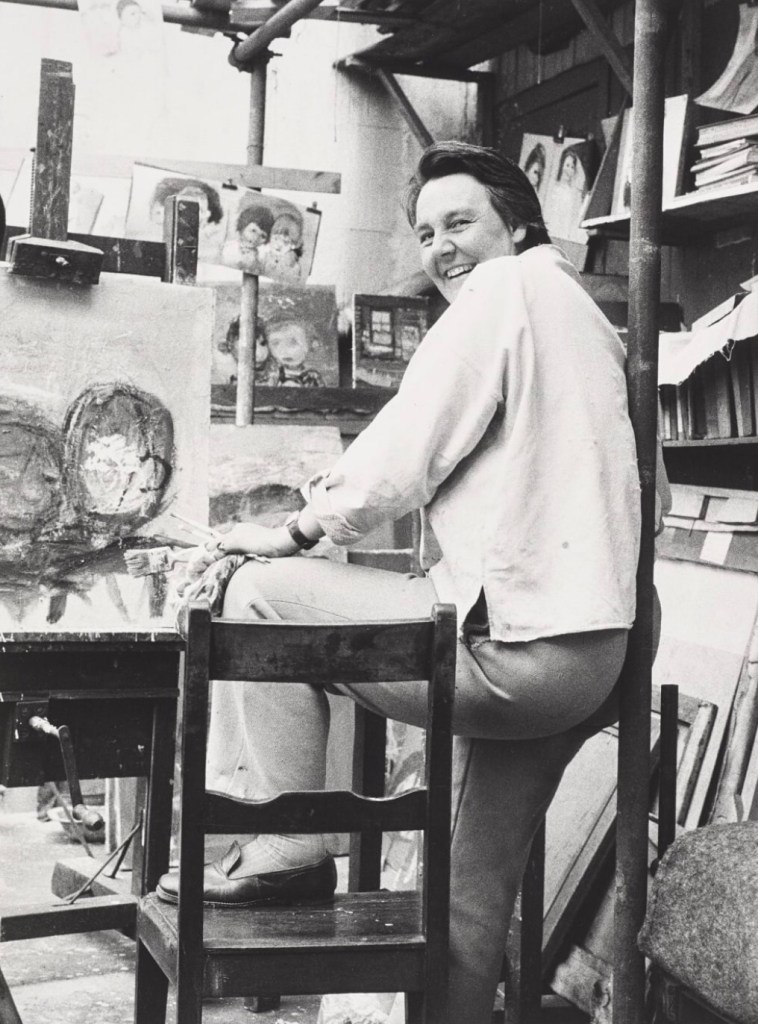

Fine Art Society Edinburgh, Joan Eardley 6-29 May

I’ve written about the forthcoming #Eardley100 celebrations before, and am hoping to write about her again several times this year. While the centenary celebrations are happening across Scotland (especially at Paisley Art Museum and the Hunterian in Glasgow), this exhibition at the Fine Art Society on Dundas Street in Edinburgh pairs works by Eardley with photographs of her in her studio. I’ve long been interested in our obsession with artists’ studios (the weird preserved Paolozzi studio at Modern Two is a great example), so I’m really curious to see this combination. It also ticks off a major ambition for me, which is to visit more of the galleries on Dundas Street. From the outside, they aren’t the most welcoming, but to learn more about Eardley, one of the best artists I’ve encountered since moving to Scotland, I’ll brave it.

Restless Worlds for MANIPULATE Festival: Lyceum, 22 April-2 May

This is why everyone should go to their local art school’s degree show (happening online this year, watch this space). At the ECA Degree Show in 2019, I came across an artist called Chell Young, who works to create miniature worlds that make you feel like you’ve had one of Alice’s EAT ME cupcakes. I’ve followed Chell’s work since, and that’s how I came across Restless Worlds. MANIPULATE Festival has commissioned eight Scottish artists to create kinetic sculptural works, displayed in windows, alongside a short story or soundscape that you download to your phone. While I’m especially looking forward to seeing what Chell has created, the whole project sounds fascinating. In Edinburgh, it is happening in the windows of the Lyceum foyer but there are projects planned for Glasgow and Aberdeen too. More info and tickets here.

Christian Newby at Collective: 13 May-29 August

I’m sure lots of Edinburgh residents have braved the climb up Calton Hill for a lockdown walk, just to feel *something*. Well, from early May we will be rewarded with an open-for-business Collective Gallery at the summit. The exhibition they’re emerging from lockdown with is by Christian Newby, and features a large-scale textile called Flower-Necklace-Cargo-Net. This tapestry, made with industrial carpet tufting techniques responds to the building, which originally housed an astronomical telescope. Christian’s work explores ideas of craftsmanship, labour and the use of machinery in the fine and applied arts. I am intrigued by the description and I really want it to be absolutely massive. We all love a large scale work.

There will be so, so much more to talk about and explore, so please consider this an initial scanning of the Edinburgh art horizon. Other things I want to explore further are the Fruitmarket Gallery reopening after its refurbishment, The Normal exhibition at the Talbot Rice Gallery which explores the pandemic, the ECA Degree Show and the Art Festival. I’ll keep my ear to the ground and post more recommendations as and when.

Alongside all that, we can never forget our old favourites. One of my first tasks when the Scottish National Portrait Gallery opens on 30th April is to go and visit my old pals, David Wilkie and Duncan Grant, to check they’ve been OK over the past year.