Some exhibitions have an unofficial soundtrack in my mind. Francis Alÿs’ Ricochets at the Barbican, which closed a couple of weeks ago, has had Whitney Houston’s The Greatest Love of All bouncing around in my head. The song starts with a gentle falling scale on the synth, and then Whitney comes in with the words: “I believe that children are our future/ teach them well and let them lead the way… let the children’s laughter remind us how we used to be.”

I’m a woman and I’m 32. That means that I am almost daily drawn into discussions of children. People ask me why I don’t have them, or if I’m wanting to have them. I’m an auntie and a guideparent. Some of my closest friends have babies, toddlers, kids in primary school. Some are wanting babies and it isn’t happening for them at the moment, some have had miscarriages and lost unborn children. I kind of knew the phase would come, when this would be the main topic of conversation dominating my life, but I had never expected an art exhibition to bring me back to it once again.

I’m with Whitney, I do believe children are our future. I think that artist Francis Alÿs does too, which is why he has spent years and travelled the globe collecting and documenting children’s games, which have been compiled together in beautiful, moving, sensory-overload-inducing multi-screen installations for his exhibition at the Barbican. The photos I took weren’t great, but the most wonderful thing about the project is that all of the Children’s Games videos are available online. You can explore the whole roster here and I’ve linked to specific ones in this post.

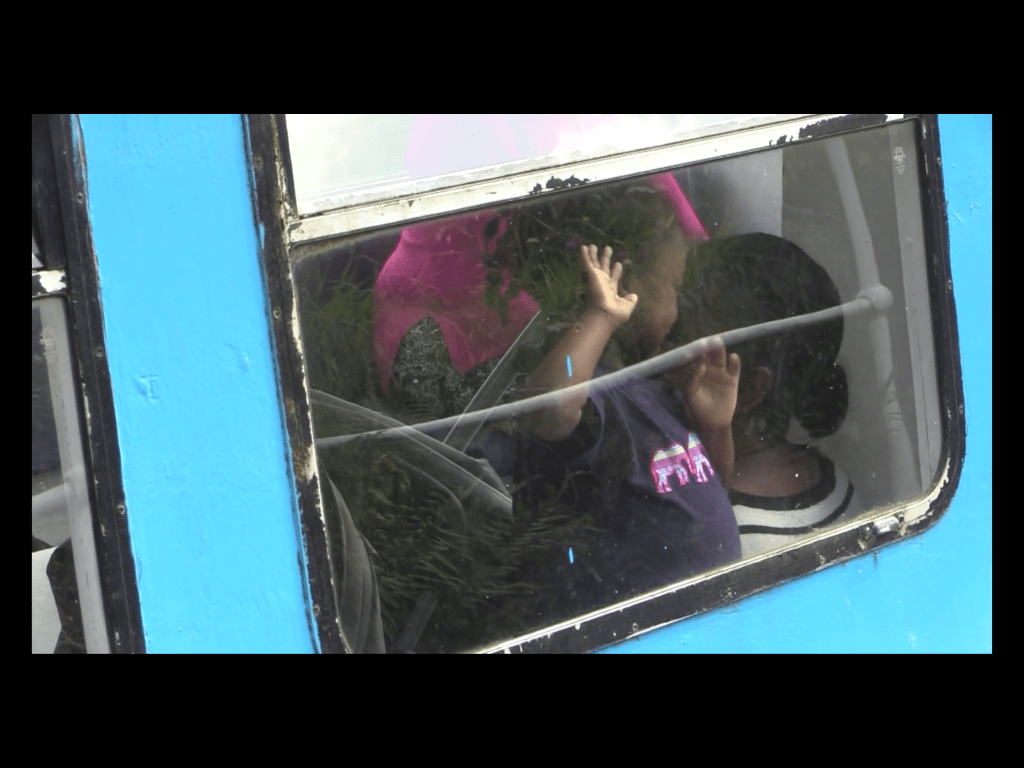

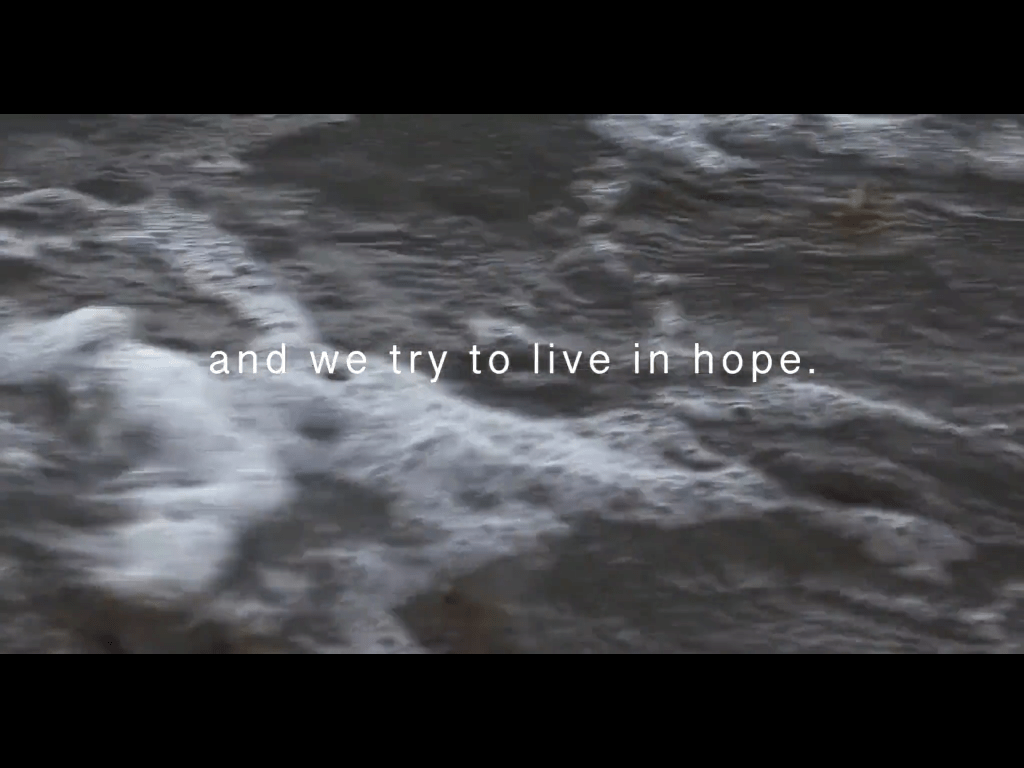

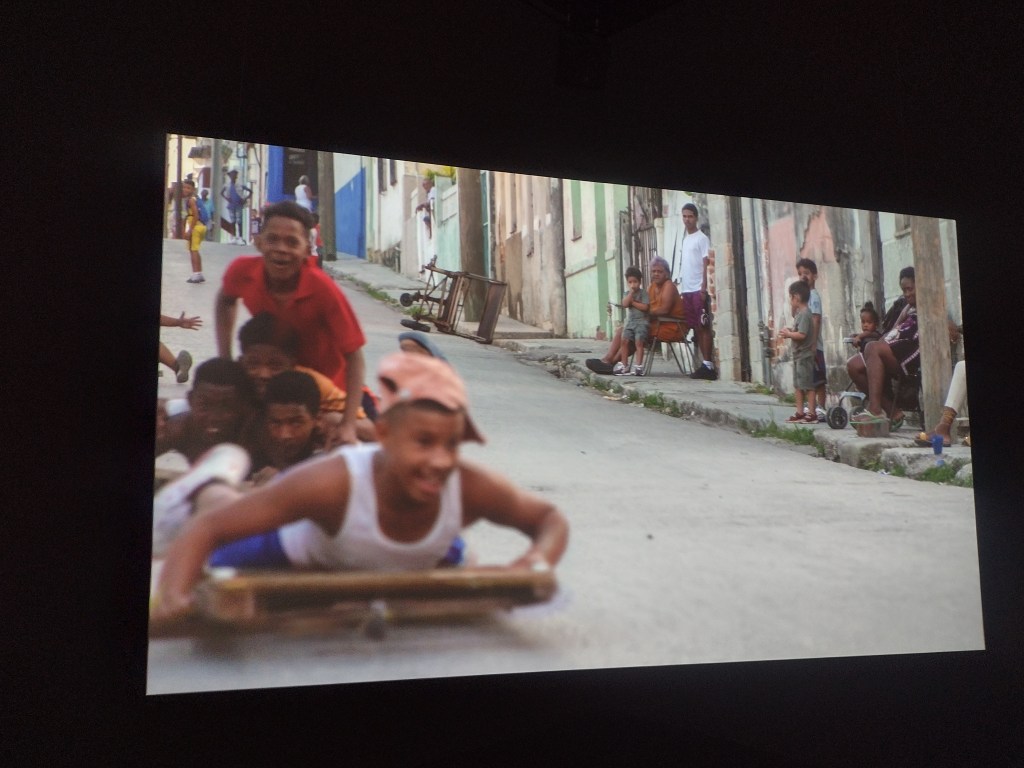

I loved immersing myself in the worlds of these children, as they raced perilously down hilly streets on makeshift go-carts, as they played “Doctor Doctor!” in a yard by a cold-looking lake, as they raced snails on concrete or flew kites, skipped and skimmed stones. They enliven and brighten and spark joy wherever these games take place. Even in war zones, places decimated by wars now over, in refugee camps, their flame and zest for life burns so brightly. The sensitive curation at the Barbican brought this home: when children play in barren wastelands, they are no longer barren. It kindles a moment of hope.

La Habana, Cuba, 2023

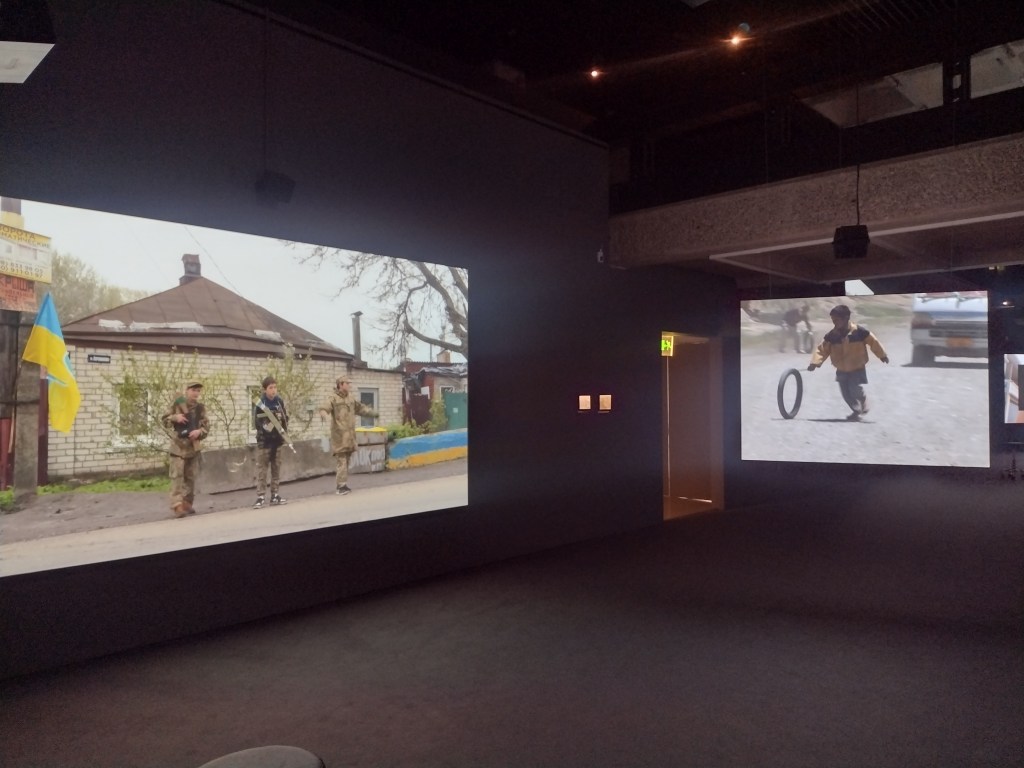

In one of the exhibition’s longer videos, Parol, three Ukranian pre-teen boys are dressed in khaki and have wooden rifles, daubed in yellow and blue, slung over their shoulders. As the accompanying text explains (beautifully written for each game by Lorna Scott Fox), the boys “act out a grown-up duty: to uncover Russian spies… Cars are flagged down, IDs requested, trunks inspected. A password is demanded: “Palyanitsya”, the name of a traditional Ukrainian bread, and a word that Russians can’t pronounce right.” While the drivers of the passing cars appear to be cheered by their interactions with the children, it’s a perilously pertinent reminder that in a few years, these boys won’t be playing anymore. They’ll be on the front line. The existence of innocence always implies the loss of it.

Kharkiv, Ukraine, 2023

In Haram Football, a group of lads between 8-15 years old gather in the streets of Mosul, Iraq, to play a game of collective imagining inspired by ‘the beautiful game’. Haram means ‘forbidden’, and football was forbidden under the rule of Islamic State. In the shadow of that regime, these boys perfected their craft of playing football without a ball, a collective pretending, all in agreement where the ball bounces, rolls and flies through the air. They shake hands and once the game starts, they jostle, dribble and leap for headers. All around them there’s rubble and collapsing buildings, the sun is setting. At one point, a tank drives straight over their makeshift goalpost, the boys just rebuild it and carry on. They disperse into the rubble and the shadows at the sound of an explosion or gunfire, but return at the end under the cover of darkness, to announce their names paired with their favourite clubs.

Mosul, Iraq, 2017

It is utterly impossible not to think of Gaza. Back in May, Unicef estimated that 14,000 children had been killed in Gaza, with 17,000 of them unaccompanied or separated. Obviously that number just keeps on going up. While I’m sure that Alÿs will be visiting Gaza to document children creating games and hope from within whatever rubble is left, it is brutal and sickening to know that the children who do survive there will inherit decades of trauma, no matter how strong their resilience is, no matter how skilled they are at continuing to create joy even among the horror. I’m reminded of Greta Thunberg’s speech to the UN in 2019: “you come to us young people for hope? How dare you.” Yet we keep on turning back to children to kindle hope in the despair and darkness, to create something better than we have. They have so much resting on their small shoulders.

If hoping is a radical act, then having children surely must be the most radical act of hope. For me, in my head, I’m still the girl in the blue summer dress weaving through the cityscape and avoiding stepping on the lines, not one of the earthbound, onlooking adults. That is the magic of Alÿs’ project. It reminds us of the beauty and fragility of youth but also presents the language of play as the universal one, the one that connects us all, if we can only hear their laughter, to ‘remind us how we used to be’.

Hong Kong, 2020