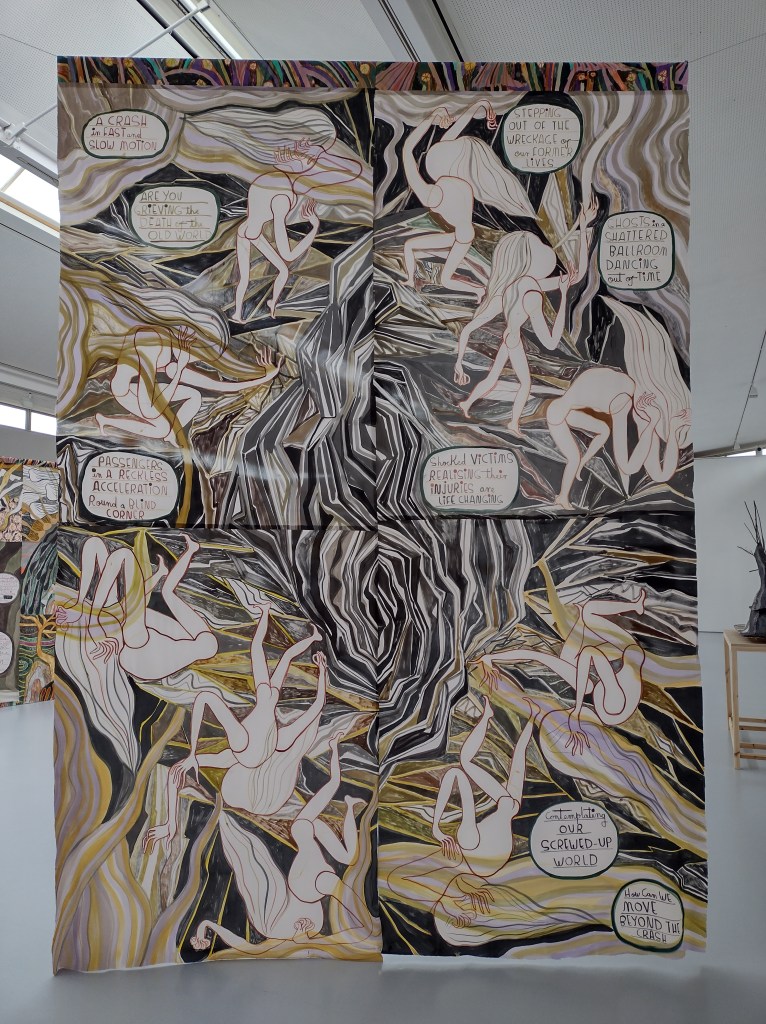

I ask myself how can it already be the end of April. What happened to the first third of the year? It seemed to have passed me by without me noticing, meanwhile the world plunges from one crisis to another. I find myself asking, ‘was it always like this?’ Did we always lurch from tragedy to crisis in a never-ending cycle? Have I only started noticing now, after living in a pandemic-induced state of hyper awareness? Or are things just particularly bad at the moment?

War, suffering, poor health, exploitation, callous political decision-making. It seems to be closing in on every side. Has it always been like this?

Four months since my last blog post and the time just keeps on ticking away. The truth is, in times like these, I don’t feel like I have much to say. Or maybe I just don’t feel like any contribution I could make adds much value. The old saying, “If you don’t have something nice to say, then don’t say anything at all”, is pretty deeply ingrained in me, and I don’t have anything nice to say about the times we’re living in. They’re scary, depressing and disorientating, and sometimes it seems like the only alternative (for the privileged ones like me) is to wrap ourselves in a comfort blanket and disengage – I actually re-downloaded Candy Crush and got to level 306 – my way of wishing it was 2015 again. Sometimes, you just don’t have anything to say.

I haven’t seen much art, for one thing, which is a big contributing factor in not having much to share here on the blog, or on Instagram. I went to the Louise Bourgeois exhibition at Hayward Gallery, and while I loved the huge spider and appreciated the dark, uncanny bone sculpture installation, it didn’t make me want to write. The show was busy. The photos I took were blurry. And perhaps I just didn’t need more heavy subject matter to struggle with in my free time – Bourgeois’ art is about as far as you can get from light and breezy.

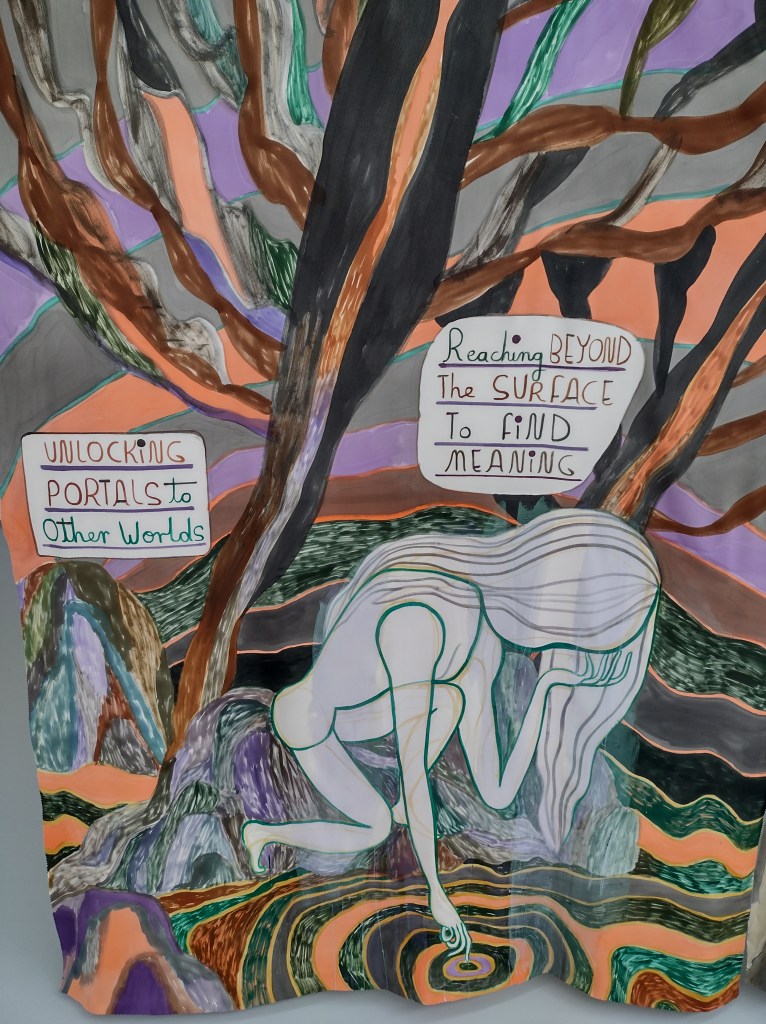

Despite my personal reaction to the weight of this show, I continue to believe that engaging with art that seems difficult can be enlightening, illuminating, and can give us tools to help us process difficult things. Art can say things we don’t want to, or that we don’t have the words for. A few weeks ago, it was on this basis that I decided to use my Instagram to “highlight some artworks that speak to what’s happening in the world over the coming weeks, if that doesn’t seem too crass”. The aim was to post a couple of works per week, broadly related to the displacement of people and refugees, with the Ukraine crisis unfolding on our doorstep.

A couple of months prior, I’d posted Dark Water, Burning World (2017) by Issam Kourbaj, an unforgettable work made up of boats, packed with burnt-out matches that resemble people. I wanted to try and make the effort to promote works and artists that engage with, rather than shirk, these difficult themes. But it tuned out that was far more challenging than I could’ve anticipated, with research becoming draining as the overarching complexity of posting artworks about refugees made me hesitate. The very fear of being crass or insensitive or saying the wrong thing was enough to shut me up. These are real people’s lives. Is it exploitative, or somehow trivialising, to wrap them up into bitesize chunks of ‘content’? Welcome to my brain. There are a lot of rhetorical questions.

Art that is fraught with difficulty is something Mary Beard grapples with on her latest excellent two-part series, Forbidden Art. I think I have a fairly sturdy threshold for engaging with art and film that can make me feel uncomfortable (the example I pride myself on is that I loved Julia Ducournau’s 2016 film, Raw), but I was surprised at how I found some of these works, including Martin Creed’s Sick Film, and Marcus Harvey’s Myra, extremely challenging. I’d love to see the ratings on the show, which aired on the BBC at prime time on two Mondays in February. Surely I wasn’t the only one who felt genuine nausea as Mary broke taboo after taboo.

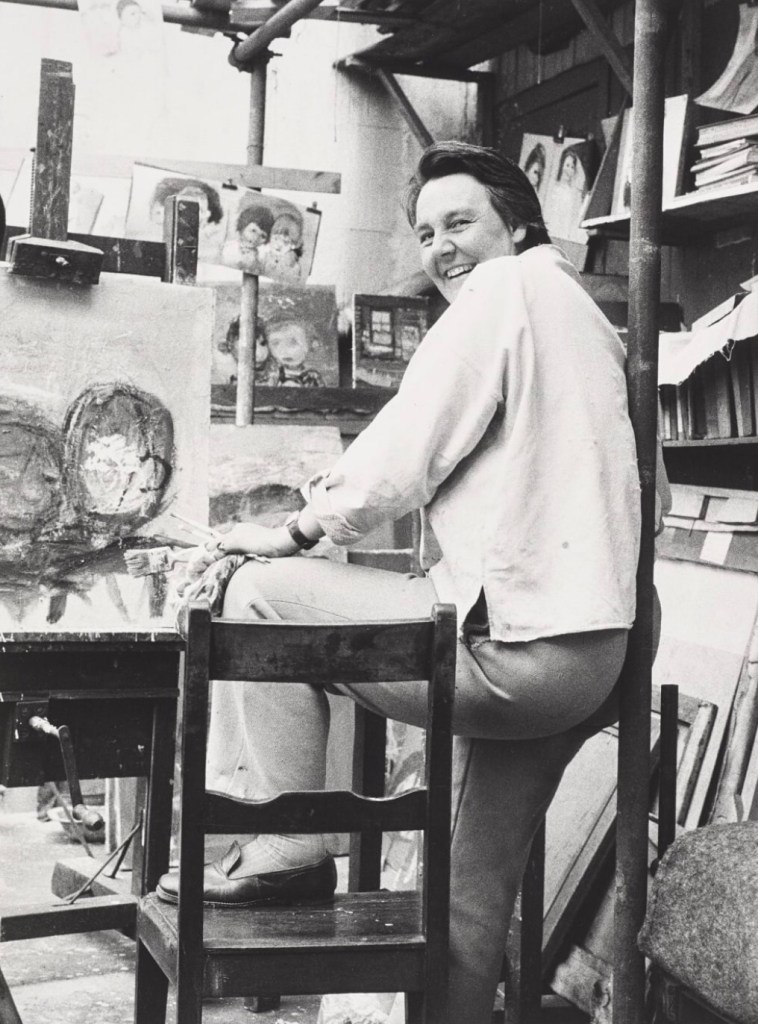

Probably the most shocking image of all from the series was Peter Howson’s Croatian and Muslim (1994), which depicts the rape of a woman with her head being shoved down a toilet. Howson was an official war artist in The Bosnian War (1992-95), though the work since has attracted controversy for being based on eyewitness accounts, rather than direct observation. Whatever the circumstances, the image points to what we now know for certain: that rape was used as a weapon in the conflict (Wikipedia estimates between 12,000-50,000 women were raped). The stories emerging from the war in the Ukraine suggest the same. As I hear this news, I have the grim realisation that I am not surprised.

In the end, I just posted two works, Tarifa by Daniel Richter, and Soleil Levant by Ai Weiwei. They are both works I’d encountered before, which felt more natural than specifically seeking out refugee-themed works. If you google ‘art about refugees’, one suggested piece that pops up is Banksy’s ‘Son of a migrant from Syria’, (2015), a mural that the world’s most famous anonymous street artist created in the Calais Jungle, which depicts Steve Jobs as a migrant. But the message behind this idea, that among refugees the next Steve Jobs might be lying in wait, is way too simplistic, clumsy and misses the point entirely. The point of welcoming refugees is not because of the part they may end up playing in global capitalism, or because they look and live like us.

Building these narratives into a piece of artwork is challenging, and so much of the art I came across didn’t sit right. Even Jeremy Deller’s poster artwork, Thank God For Immigrants (2020), which I have a copy of, delivers a cloudy message that is (intentionally) fraught with complexity.

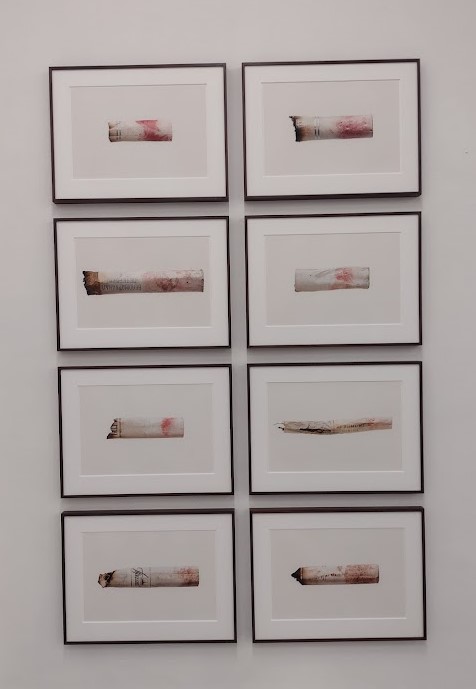

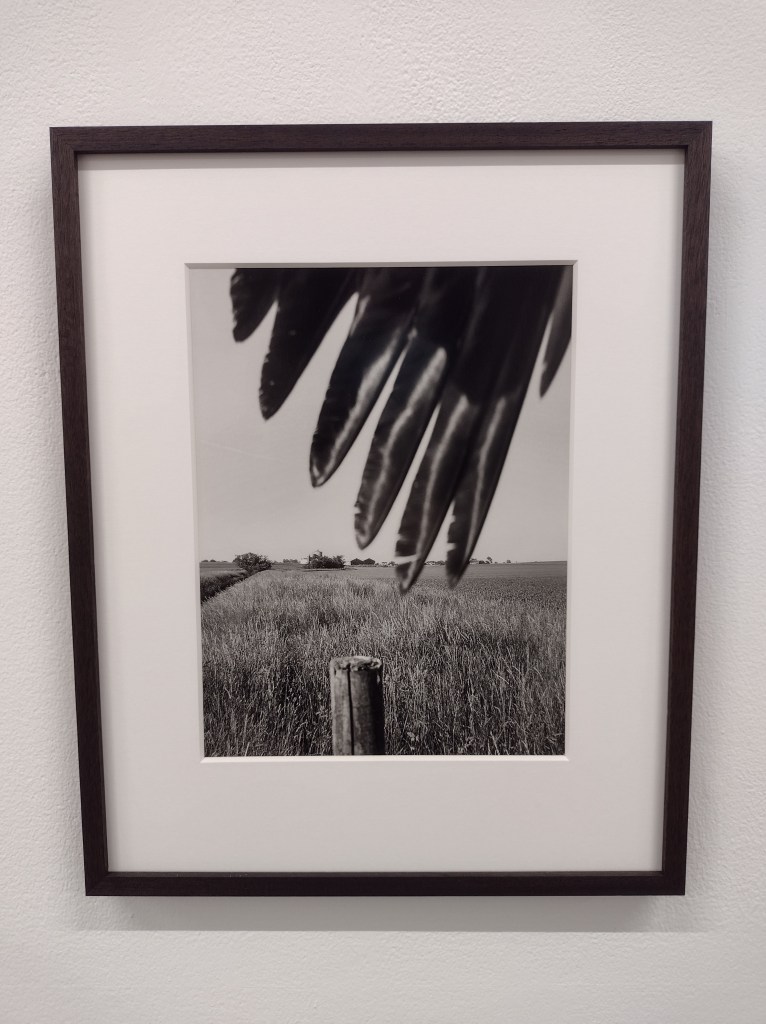

Someone who has done a significant amount more meaningful thinking and research about this than me is art writer Tom Jeffreys, whose brilliant piece, reviewing Iman Tajik’s Bordered Miles performance for Glasgow International, broaches the issues of borders, safety, identity and what is at stake for undocumented immigrants and refugees in this country. Tajik’s work is built upon lived experience as a detainee at Dungavel detention centre, but his art, which encompasses performance, photography and installation, seeks to widen the lens beyond his own life and perspective, to deal with ideas, not stories. It is the kind of nuanced work with a scope and resonance goes way beyond that of an Instagram feed. The kind of work that shows us that if we want to engage with art, we may as well do it properly. That can sometimes take stamina, research, and courage.

When we encounter art, we may not always like what we see. We may want to look away and in some moments, the act of avoidance may feel like be our only option, for self-preservation and protection. As long as we clock that urge to shy away, I think that’s ok. In the meanwhile, artists will continue to respond to crises in ways that can range from the effective to the offensive. And when we do decide to re-engage, artists and artworks will be ready to receive us, to educate us, and to challenge us.