For someone who writes about art, I will sheepishly admit that I haven’t read much art criticism. There were lots of academic papers while I was at university, but actual art magazines always seemed unattainable to me: sitting in rows at the entrance of the library, shiny pages, heavy and untouched by anyone, looking rich and intimidating. I used to wonder who those pristine publications were for, as I walked past them to go and bury my head in a battered old catalogue, full of black and white photo reproductions and not too much text.

I’d heard of Olivia Laing through friends. One gave me a copy of Crudo, her first work of fiction, a couple of years ago, while another mentioned I might like The Lonely City. Then last summer a copy of Funny Weather, a collection of her essays, landed in my lap through work. When I finally started it, what struck me most was that this writing was both easy to read, and somehow had an air of poetic stillness to it. The force of the voice, the strength of the writing, would be enough to carry you through, even if you weren’t that into art. Take her description of wandering through the Wallace Collection, for example, an experience which I also wrote about last year.

The Wallace Collection was almost empty. I drifted through the violet and empire-green rooms, with their washed-silk walls… The Fragonard girl still hung on her swing, suspended in thick air; a goose lay perpetually unplucked on a kitchen table. Nothing beats paint for stopping time cold.

From ‘Dance to the Music’, December 2017

Many of these essays started life as columns for Frieze magazine, but this didn’t feel like reading art criticism. Laing’s observations felt more like the notes in the margins from some recent but only half-recognisable memory, observing life, love, intimacy, rage, humanity, shame, identity. Her subjects are broad. One essay can take in Patti Smith, killer whales, abortion rights, as well as a performance at the Barbican, and she manages to connect them all cohesively. I learned more about later 20th century American art than I had ever bothered to before. Biographies of artists and writers mix with recollections of her own experiences, and every now and then you get a glistening nugget of a sentence which you just have to let soak in.

“It was a very bright day. The sun was so low that every grain of sand cast a shadow.”

From ‘Between the Acts’, November 2018

There are many fascinating things about reading these essays, and one is that they allow you to time-travel into what, since the juggernaut of the coronavirus pandemic, seems like distant history. They are dispatches from the recent past, and the unfolding events (the refugee crisis, Trump’s election, Brexit, Nigel Farage’s “breaking point” poster) are examined with unflinching insight and a healthy dose of terror. Funny Weather places art solidly in its political context. It shows us that news ages quickly, but reminds us that many of these threats still exist: they remain there to call out, and fight against, during and after the pandemic. The way visual signs and symbols are used in the political landscape will always be a fruitful trove for artists and art observers to analyse. I would love to get Laing’s take on all the union jacks we keep seeing in politicians’ homes. Deeply sinister, would be my guess.

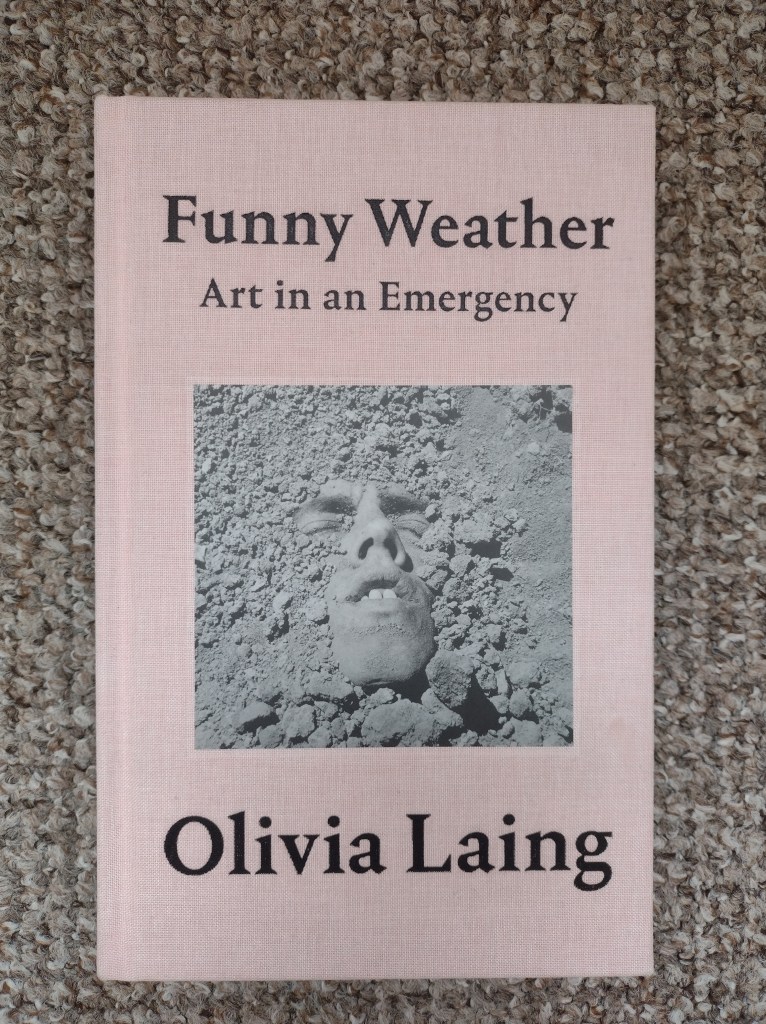

That the essays have been compiled into book form is a joy, because the book itself is a very beautiful object. Its pale pink, candyfloss-coloured cloth cover contrasts shockingly with the photograph: a close-cropped image of David Wojnarowicz’s partially-buried face, gritted teeth, covered in dirt and dust, called Untitled (Face in Dirt), 1992-93.

With such a strong cover, the book’s complete lack of images inside was a disappointment. Reading one article or essay online, it is easy to search for the images on my phone simultaneously. With a book, all that research is far too time consuming and disrupts to the act of reading. Asking people to read about art without including the visual reference point is a swing and a miss. It assumes a certain level of knowledge or awareness of the artists’ work, which I definitely didn’t have for every piece or even every artist discussed (I hadn’t heard of Sargy Mann at all, but now I’m glad I have). I wish they’d at least inserted a few pages of images. Or, how about a link to an online index, where we could browse all the works mentioned, side by side? That would be an amazing insight into Laing’s critical eye. That way, we could see what she is most drawn to, at a glance.

The major take-home for me was that Laing’s writing shines brightest when describing the work and lives of queer artists. Her essay on Derek Jarman, ‘Sparks through Stubble’ (2018) completely charmed me, partly because it lets us in to her own life too. Her mother was gay, and she grew up in ‘a village near Portsmouth where all the cul-de-sacs were named after the fields they’d destroyed’. I later discovered that this essay was written as an introduction to a recent edition of Jarman’s Modern Nature, which I added straight to my TBR list.

Through exploring the world of Jarman, Laing writes about the Aids crisis with such empathy. Her essay on David Wojnarowicz, who died aged 37 of Aids-related complications, is a plea for compassion, and re-opened my own eyes to the very recent reality of the gay community living every day in fear, their very existence politicised: ‘What does it mean if what you desire is illegal? Fear, frustration, fury, yes, but also kind of a political awakening, a fertile paranoia.’ Wojnarowicz was completely unfamiliar to me, but Laing’s writing about him illuminated connections to a young artist called Graham Martin whose work I was familiar with through Instagram. Martin’s depictions of empty, dilapidated warehouses, with naked male bodies barely distinguishable in the shadows, brought Laing’s essay to life for me. Making this conceptual link between Laing, Wojnarowicz, and Martin, I could feel the synapses in my brain lighting up. It all made sense.

Since starting this blog, a few people have asked me: if I want to learn about art, where should I start? What should I read? How does it work? I haven’t always known how to respond. If you want to read what other people have to say about art, if you find it helpful or illuminating, that’s great (thank you for getting so far with this review!) But reading Funny Weather has also made me understand that while great art writing like Laing’s can stand up by itself, the best way to engage with art is looking at it first, reading about it second.