There have been some interesting developments lately in the arts funding sector in Scotland, as well as in the UK more widely, and so I thought I would try to put some of my thoughts down, to stop them swirling round in the echo chamber of my own brain. No one asked for my two cents, much of this is based on my personal experience, and I have more questions than answers really, but here they are.

To begin with, some context.

When I joined the National Gallery’s Development (aka fundraising) team in 2014, the Gallery was in the middle of a process of transitioning their security staff from an in-house service to an external security provider. After all, it’s cheaper to outsource this stuff than pay for your staff’s pensions. It was a horrible process, and involved many of the Gallery’s knowledgeable and dedicated security staff, who’d been working there for years, being transferred over to work for a big security company which covers far more than just museums and galleries. At the time I was 22, I’d just landed my first arts job and didn’t really understand the implications of what was happening – or maybe I didn’t want to understand. But it was part of a long process where, under successive Conservative governments, the arts have been pressured to function as businesses for their very survival. Private venue hire and increased reliance on philanthropic donations, both corporate and individual, has followed as part of this very conscious and politically motivated strategy.

My early career background as an arts fundraiser means my whole view of arts funding is rather institutional. For fundraisers, it’s a question of whether the institution can survive, that’s the bottom line. While there are due diligence processes on what is morally and ethically acceptable in terms of funding, this survival mentality shapes everything. At places like the National Gallery, the idea was always that we wanted to keep the nation’s beloved and beautiful art collection free and accessible to all, which was a huge personal motivator for me.

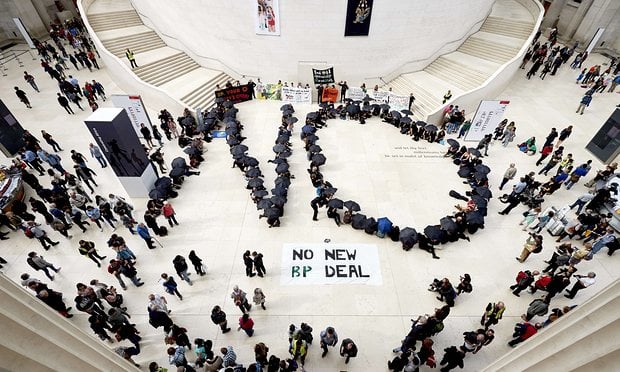

A decade later, I’m no longer an arts fundraiser but the conversation around it has evolved hugely. As the climate crisis unfolds at an alarming rate, most museums and galleries have now dropped oil companies as corporate sponsors (except for the Science Museum and the British Museum). Activists staged some incredibly striking protests that gained media attention and slowly filtered into the public consciousness.

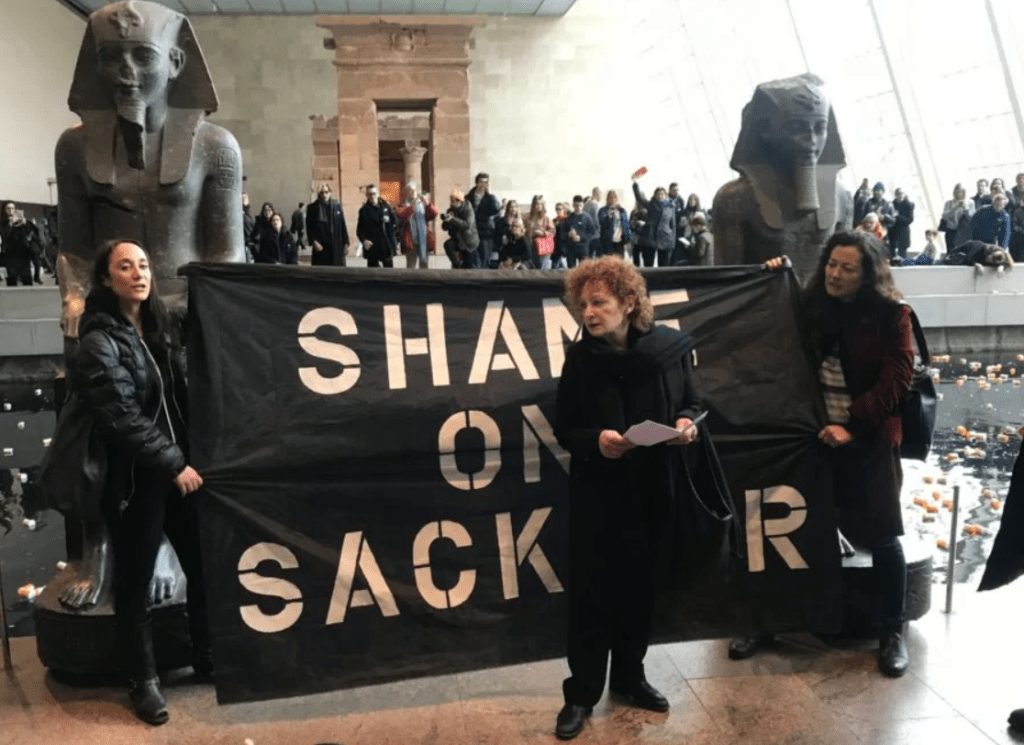

A significant part of this shift was the tireless campaigning led by artist Nan Goldin to get museums to stop accepting money from the Sackler foundation. The Sackler family has profited from the opioid crisis for decades, and were huge donors to museums and galleries across the globe. If you aren’t familiar with it, I’d recommend watching All the Beauty and the Bloodshed which documents the story. There is also Empire of Pain by Patrick Radden Keefe which investigates the subtle power of private money to influence public institutions. The fact that major museums dropped the Sackler foundation, and removed their name from their walls, shows that activism can work. It shows that there are some ethical lines that must not be crossed.

The difficulty is everyone seems to have differing views on where that line should be drawn. Until recently, Edinburgh International Book Festival (also a former employer of mine) had defended its decision to accept funding from Baillie Gifford, an asset management firm with their headquarters in Edinburgh. Cut to a few weeks later and the Book Festival have, albeit reluctantly, cut their ties with Baillie Gifford following pressure from authors, artists and the public, with activist group Fossil Free Books at the helm.

It gives me hope that people care about, research and question how things are funded, rather than just blindly accepting and consuming them. When the Book Festival decided to drop Baillie Gifford, I will admit that it felt like a win. It was a huge win for activists who’d pointed out repeatedly that Baillie Gifford has holdings in fossil fuel companies and software companies used by the Israeli military, and is therefore complicit in the ongoing genocide of Palestinians.

However, now the dust has settled, a more cynical standpoint would say that this whole debacle has done significant damage to the arts but will have very little impact on the asset management firm and where their investments are. At the end of the day, they exist to make profit. They won’t be taking strategic advice from a Book Festival on divesting. They’ll continue to do what they do and they won’t be influenced by activists. That’s the cruel reality of capitalism. Incidentally, when Patrick Radden Keefe won the Baillie Gifford Prize (worth £50k) for Empire of Pain, he pointed out the irony. I’ll be very interested to see what this year’s winner of the prize will say.

Sometimes, I feel frustrated that the arts is subject to such intense scrutiny, where it seems like everything else has a free pass. Last year, the same weekend when Greta Thunberg pulled out of the Book Festival on the basis of Baillie Gifford’s investments in fossil fuels, I went to a mountain biking world championship event that was funded by Shell, their branding plastered all over the race. My mind reeled as I thought of how different standards were expected of art and sport.

The reason the arts is held to such high ethical and moral standards I guess is because they are generally believed to be a force for good. Most good art is political, it challenges us, makes us think in new ways, and see different perspectives. [I would hasten to add that the commercial art world is a whole other kettle of fish that I know very little about but seems deeply unethical and weird, with a HUGE carbon footprint and mainly the preserve of millionaires. They don’t seem to come under much critique but I guess that’s because that world is so far from most people’s reality.]

It feels sometimes like it’s impossible to exist in an ethical way within a system and ecology that is both exploitative and unsustainable. As one friend of mine, an arts fundraiser, said: “They’re still gonna do bad shit to the planet, let the arts have the ££££.” It’s a pragmatic approach, and it acknowledges that we’re just surviving on whatever we can get our hands on as the world burns. What does that mean for us as a society and for the things that we value?

At an Art Workers for Palestine Scotland event I attended in March, we had some interesting conversations. I was expressing my concern that without funding the arts won’t be able to deliver their programmes, exhibitions, events and keep on functioning to the same extent. The session facilitator replied that maybe that was just what had to happen, better that than accepting unethical funding. My (institutional) mind was blown, but maybe he was right. That means we’ll have to buckle our seatbelts and what’s coming will be a wholesale reimagining of what these arts organisations look like. Some critics of the Fossil Free Books campaign, such as a glib Marina Hyde on The Rest is Entertainment, have said that as a direct result of the withdrawal of Baillie Gifford funding means that outreach, work with schools and community programmes will get cut from festivals. I’d argue these are the bits these institutions should be rediverting their core funding to, they’re the parts that need to survive this turbulent future.

A word about arts workers

I wanted to take a moment to acknowledge the people who reside mainly behind the scenes in the arts and culture sector who work incredibly hard, who are under immense pressure to deliver. They have to juggle relationships with both artists and funders. They are predominatly women, bending over backwards to keep everyone happy and keep organisations afloat. Most of these people work for arts institutions out of love, and they put their blood, sweat and tears into making those places function (places that don’t always love them back). Unfortunately unless the government steps up their funding of arts organisations as places of intrinsic value, instead of treating them like businesses that have to prove their worth, it’s likely that the secure salaried posts at these organisations will shrink and everyone will be forced to work on insecure, temporary contracts, thus making the sector as a whole precarious. It’s already precarious: these workers know that there’s a queue of well qualified and dedicated people right outside the door ready to do their jobs if they don’t want to any more. Hence why everyone is, for the most part, overworked and underpaid.

So, it’s a mixed bag of feelings and I don’t know where we are going to end up. The whole issue is complex, divisive and quite depressing, but I still firmly believe that the arts, and people’s need to engage with art and culture, will endure. But these things are fragile and need to be nurtured through collective community endeavour. We will need all the imagination and creativity we can get. Maybe we can find the space to grow beyond the institutions we cling to so tightly, but I don’t know how.

I’ll keep following these stories with interest and hope to keep on having conversations about this. Some questions I will be asking myself which might be interesting to consider:

- Can we be both principled and pragmatic in our approach to arts funding?

- Do we side with hope or cynicism?

- What does art/culture look like without institutions?

- How can we try to live and create ethically within an unethical system?

- How can we make access to art/the arts equitable for all?

What can we do?

- Buy books from independent bookshops or use your local library

- Support artists by buying their work and attending events

- Keep talking to each other, follow accounts tackling these thorny issues

- Vote

I am interested in continuing the conversation about this so if you would like to leave your comments then please do go ahead.