A few of my friends, who know I’m interested in public space, memorials, statues and public art (because I’m constantly banging on about it) have asked me what I think about the debate raging over statues in Britain. In order to try and express this, I’m going to draw on something I wrote during my MSc at Edinburgh College of Art last year, which takes two case studies from the USA as its main examples.

I want to show that public art, including performative rituals such as protests, can usefully inform debates around our identity, and that a frank discussion of visual culture in public spaces remains vital for understanding the public sphere we operate in today.

The essay was written for a class called Art in the Creative City, run by Harry Weeks (now at Newcastle University ). I’ve taken out large chunks, removed the footnotes and edited it fairly heavily in the interest of making it more accessible. If you want to see my reading list or access the original essay, send me a note in the comments, or DM me on Instagram. Events are changing so fast. ‘Statue defenders’ are holding protests at London’s Cenotaph as I write this. I’ll try and keep up with the momentum. Asterisks mark the start and end of the essay section, before sharing some of my thoughts on the situation in Britain.

***

The question of who is commemorated and who is erased in public space is one that is charged with different interpretations of history, politics and the concept of identity. Historically, public art has reflected the power of the dominant forces in society, because having a presence in public space, being deemed worthy of representation, is a signal of power, status and money.

The turbulent history surrounding the equestrian statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee in Charlottesville, Virginia, is indicated by the renaming of its location three times over the past three years. Formerly Lee Park, it was briefly to become Emancipation Park, and now is known as Market Street Park; the difficulty of finding the right name for the space directly connects with the controversy around the statue of Lee. The monument was erected in 1924 as part of the wider movement known as the ‘Lost Cause’, which intended to frame the participation of the Southern States in a Civil War narrative of heroism and gallantry, with similar monuments erected in nearby Richmond, Virginia and further afield. In Charlottesville, city councillors took the decision to remove the monument in the spring of 2017, though its removal was delayed pending a legal challenge. During the delay between March and August of that year, the statue became a rallying point for far right groups, who protested against its proposed removal. Over the summer, a number of protests and counter-protests for and against the removal of the statue culminated in August, when violence at a rally for ‘Unite the Right’ resulted in the death of Heather Heyer, a peaceful protestor. The event was reported widely on national and international news.

As a piece of public sculpture, this statue and its interpretation as a symbol of either hateful racism or historic pride by different sides of the debate, is at the centre of these political events. The visual symbolism of the statue and the differing aesthetics that emerged around it, are therefore highly relevant. As embodied rituals, protests, marches and vigils can be read as forms of performance, which use visual tools to enhance their legibility and potency. The rallies both for and against the Robert E. Lee’s removal were no exception.

During a rally in May 2017 protesting against the removal of the sculpture, the leader Richard Spencer was heavily criticised for promoting the use of torches, which were interpreted as an symbolic visual invocation of Ku Klux Klan gatherings. Spencer’s response was to deny that the torches had any reference to the KKK, but justified their use on the basis of their ‘beautiful aesthetic’. This argument, highly doubtful given Spencer’s overtly white nationalist views, attempts to justify the use of a controversial symbol of terror on the basis of an aesthetic effect. It shows the extent to which aesthetic and political strategies are interlinked, and highlights the ways in which public art and aesthetic gestures can be (mis)used as tools for political agitation, whether progressive or regressive.

Scholar David Harvey has convincingly argued that cities as public spaces are constantly in a symbiotic relationship of shaping and being shaped by their inhabitants, through their political, intellectual and economic engagement. It is therefore no surprise that public art is persistently at the centre of debates about identity, collective memory, history and politics, and a whole range of different ideas about right and wrong, who is represented, and who is erased. The case of the Charlottesville statue of Robert E. Lee shows this in action. So far, the statue has been analysed as a magnet for far-right politics, but there are other tactics at work too, interventions that successfully question its validity as a supposedly heroic symbol.

On a purely formal level, the equestrian statue of Robert E. Lee, raised up on its stone plinth, works within the visual language of dominance and power: gazing up from below, we see nothing but galloping hooves. In 2015, prior to the council’s vote to remove the statue, the words ‘Black Lives Matter’ were sprayed on its plinth, and although removed soon afterwards, the outline remains vaguely visible. While many might categorise graffiti as anti-social behaviour and vandalism, Lucy Lippard has framed these kinds of gestures as ‘wake-up art’, and assigns them a significant role within the field of public art, with the capacity to call attention to problematic places and to galvanise communities into action. The political resonance of the graffiti gesture in this context, proven by the groundswell of support for the campaign to remove the Charlottesville statue, is indisputable. In February 2019, further graffiti covered the statue’s plinth, and it is likely that these gestures will continue to be enacted on the statue until its fate has been decided in the legal courts. In this context then, the graffiti acts as a kind of reframing mechanism, reminding passers-by and the media that the debate has not gone away. Statues and monuments commemorating military leaders who fought to defend slavery remain unacceptable to swaths of American society, and especially painful to the African-American community. The debate will continue in public life as long as these contentious symbols remain standing in shared, supposedly equal-access public spaces.

By existing in public spaces, public artworks and their interpretation are fundamentally unpredictable, just as people themselves can be unpredictable. Instead of being confined to the space of a gallery or museum, where artworks are constantly under surveillance and accessible only to a minority of people, public art is out in the open. It is exposed to all passers-by and, while this means it may exist completely unnoticed, equally it can also function as a site of intervention, either in the form of graffiti, or by being used as rallying points within performative gatherings, such as protests and vigils. It is through this very unpredictability and spontaneity that these public works can attain their meaning, and spark debate about what kind of society we wish to construct. Public art in all its forms can help to inform our debates about who is visible, who is represented in our public spaces, and can help us to articulate our equal responsibility in building our shared ownership of them.

Though the graffiti intervention on Robert E. Lee’s plinth effectively brings the sculpture back into the discursive realm and questions its validity, ‘wake up art’ is not the only option for diversifying public spaces. The right to be officially recognised in public sculpture and represented within the ‘symbolic public landscape’, to use Magdalena Dembinska’s term, is also important for the assertion of minorities’ identities.

Branly Cadet’s 2017 monument A Quest for Parity: The Octavius V. Catto Memorial, which is situated on the southwest corner of Philadelphia’s City Hall, is a useful example. The memorial is comprised of multiple elements which together form an impressive monument to an extraordinary figure – a Civil War-era activist who campaigned for the rights of African-American citizens – who is clearly deserving of recognition in the public sphere.

The monument operates strictly within the confines of the traditional aesthetic of monumental public art, through its figurative use of bronze, and its position outside City Hall. From a formal perspective therefore, it does not push the boundaries or challenge its viewers aesthetically – it is clearly designed to avoid provoking controversy. Yet this is perhaps the very purpose of the Catto monument: it allows African-Americans to assert their presence and validity within the mainstream tradition of monumental forms. The sculpture’s title, A Quest for Parity, specifically refers to Catto’s campaigns for equality. Yet the monument itself is also a reassertion of that quest for parity within public art and representation in the public arena more broadly. The monument therefore is an example of how traditional forms can also help to raise visibility of minority communities, and that their presence in the public arena need not only be represented by avant-garde artistic strategies or counter-monumental interventions.

Public art is embedded in a political landscape. In whatever form it takes, in both its inception and its interpretation, it is informed by differing ideological positions and political beliefs: what remains standing and what is removed from our parks, squares, and the façades of government buildings reflects the societies in which we live. Artworks can be deeply divisive, and can expose latent divisions within societies in ways that can be traumatic and will require healing. Art has the power to spark and intervene in public debate.

What was revered, relevant and what was commemorated in the past may not always be admirable and appropriate in the present and future, which is why those who manage public spaces need to enter into dialogues with the communities and individuals who use them. Artworks that evolve and change help us to question the notions of one fixed ‘public’, and can encourage us to embrace flexible visions of the public sphere, and recognise multiple viewpoints, helping to make those who had been invisible and unheard part of the many voices that make up public life.

***

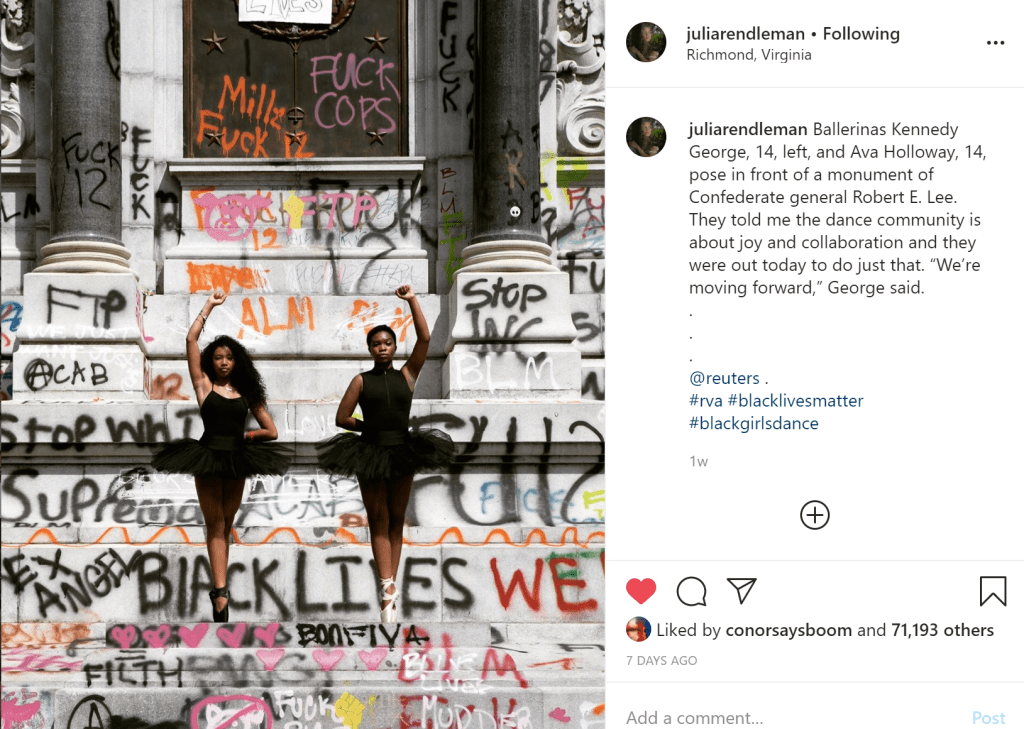

Fast forward a year and after the murder of George Floyd by a police officer, a wave of social activism has swept the US and Britain. In Richmond, Virginia, the government has pledged to remove a statue of Robert E. Lee on Monument Avenue. Images on Instagram of black ballerinas posing below the monument, now covered in graffiti, depict a significant historic moment and show the power of activism. Neighbouring Charlottesville campaigners are relieved that their state authorities are finally acknowledging the hurt these monuments have caused, and hope it will hasten the removal of Lee’s statue from Market Street Park.

In Britain, the argument over who is permitted representation in public space seems to be right at the heart of the nation’s identity crisis. There are a few thoughts I have to add to this debate, which is constantly evolving. Firstly, it is a good thing our public monuments are under scrutiny. They have remained invisible in plain sight for far too long.

The statue of Edward Colston that was forcibly removed by anti-racist protestors and symbolically dumped into the River Avon, where his ships that carried slaves across the Atlantic would have docked, was a momentous and powerful act. The act of its removal has done more to educate people about Britain than the passive existence of the statue itself ever has. As historian David Olusoga has said, rather than the erasure of history, this was the writing of it. Removed in this way is actually far better than had it been quietly taken down by the city’s authorities. It was a moment of activism, a kindling of hope that change could be possible.

For this reason, I don’t believe the statue should have been retrieved from the water so hastily, and I don’t believe it belongs in a museum. As stated above, museums are accessed by a small proportion of the populace, whereas the public space, city squares and streets, are used by us all. (Or were, until coronavirus forced us back to the private sphere, an act which though necessary and in the interest of public health, will serve to entrench the inequalities already prevalent in British society). Rather, Bristol City Council could commission an art piece which works in dialogue with the local community and their city to respond to Colston’s removal: an artwork which shows the journey of the statue from its plinth to the waterfront. Leave the plinth standing empty – the equivalent of an empty chair at a political debate. Leave up the graffiti. Use the landscape and the statue’s journey within it to teach people about Colston, about the legacies of the slave trade upon which Bristol and Britain’s wealth was built.

For far too long have the British seen themselves as the “goodies” of history, an idea that has been perpetuated by an education system that doesn’t include the British Empire or colonial rule. I had to do a history degree before I was really exposed to these aspects of our past. If we need inspiration, our European neighbours have examples of public art that helps passers-by work through the traumas of the history. The Berlin wall is commemorated by a copper line which traces the footprint of where the barrier once stood, an artwork woven into the urban fabric which educates but doesn’t erase. Britain could learn a lot from Germany when it comes to acknowledging the past through the use of public space and visual culture.

Understandably, the movement to reassess our statues and monuments has now gathered significant momentum, and other historical figures have come into focus, which has exposed some uncomfortable truths that many would rather sweep under the rug. I think, or would hope, that the vast majority of people agree that slave traders like Colston should have removed long ago. Meanwhile, figures like Winston Churchill and Robert Baden-Powell attract both support and denouncement. Many see these men as heroes, while others reject them for their support of ideologies which, while perhaps common in their day, are not to be celebrated in 2020.

I personally know that the Second World War was not won by one man, and believe that it is possible (and more constructive) to celebrate the now inclusive and welcoming Scout movement without glorifying its founder. However, when I ‘read the room’, and see who is in power in the UK, I think we may have to concede the impossibility of removing all contentious historic figures from view in this current climate. If that is the case, then we need to level the playing field by following the example of Brandy Cadet’s Octavius V. Catto Memorial: let’s commission artists to create monuments to those who have been forgotten, the historically powerless and marginalised. Edinburgh infamously has more statues of animals than of women. If we can’t topple the statue of Henry Dundas in St Andrew’s Square, let’s set up a sculpture that counteracts the ridiculous, phallic intrusion of his monument on our city’s skyline. Let’s insert the narratives of the witches who were publicly executed, the Windrush generation, the LGBT+ community, working class voices, immigrant communities and all who have built our cities into the diverse and interesting places they are today.

Public art can help to articulate and inform our very understanding of who we are, and how we operate in the public sphere, as both individuals and within the groups to which we identify ourselves as belonging. Britain is a deeply divided society, so a proper exploration of our art, which acts like a mirror, can be a way of working through and understanding these divisions. It’s not going to be an easy task. It’s not going to be pretty. There will be lots of feathers ruffled, tears shed, arguments and fights in the process, but asserting our public spaces as sites for activism and debate will be a necessary catharsis, and will enable us to ‘build back better’ in the imminent future.