This is perhaps the first of a series I’m going to call ‘crying in the gallery’. Art can move us in unexpected ways and catch us off guard at times. That’s what happened during a visit earlier this year to the Royal Scottish Academy for a look at their exhibition Dürer to Van Dyck: Drawings from Chatsworth House. It was a small exhibition featuring exceptionally high quality drawings and watercolours from the Devonshire Collection (amassed by the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Dukes of Devonshire) and usually housed at Chatsworth in Derbyshire.

As the title suggests, the exhibition featured some of the most famous-of-famous artists: Albrecht Dürer, Hans Holbein the Younger, Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck and Rembrandt. The darkness of the room enhanced the magical effect of these delicate drawings, faces peer out from history and the darkness; animals and landscapes emerge with exquisite fragility.

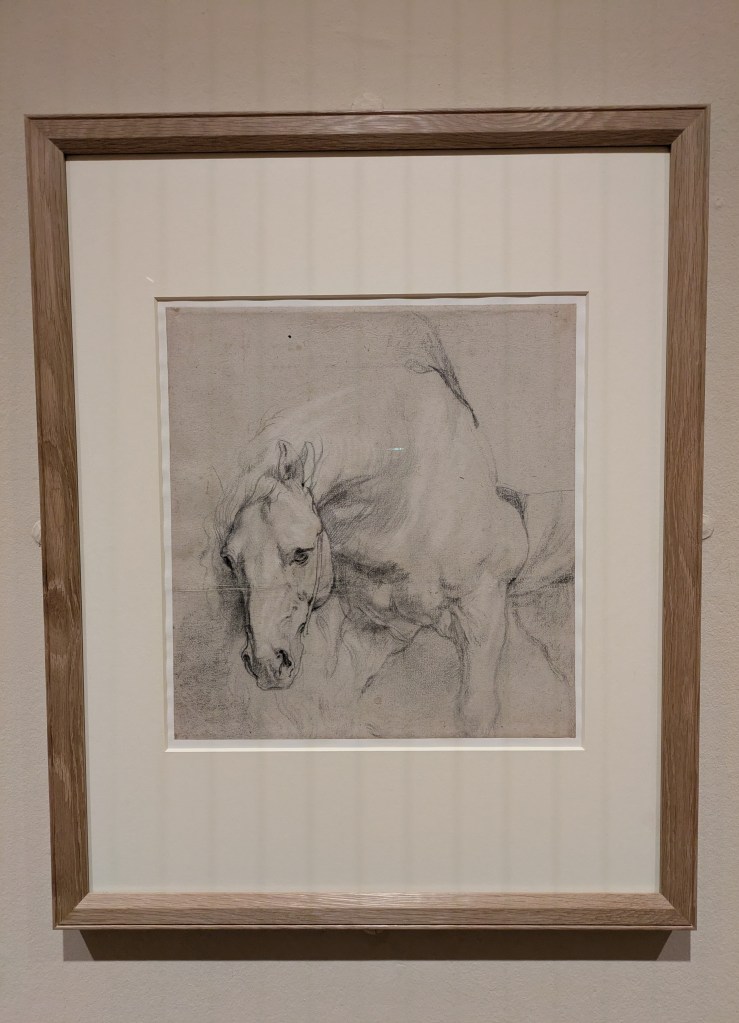

So much of what we see in drawings feels like a glance into the ‘behind the scenes’ of an artist’s process, whether that is preparatory sketches, studies for prints or tapestries, observations of landscapes, or designs for much larger works. One piece that caught my eye was a beautiful sketch of a horse by Van Dyck. Its head is lowered, its gaze fixed. It appears to be waiting patiently – you can see the fine detail from pulsating veins to strands of its mane. This was a preparatory sketch for the 1618 painting, St Martin Dividing his Cloak, an altarpiece in the Sint-Martinuskerk in Zaventem, Belgium. If you look at them side-by-side, I much prefer the drawing to the fully fledged painting. It is the most immediate art form – far more intimate than a grand oil painting in a heavy gold frame.

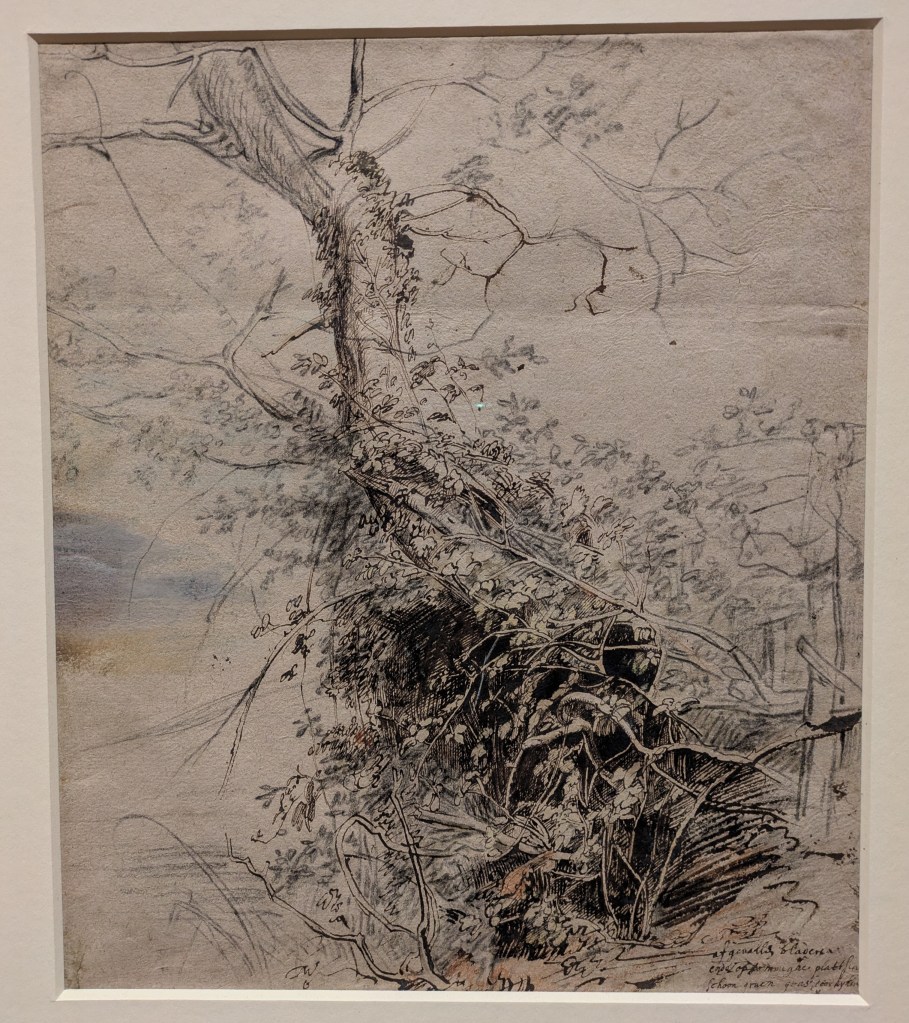

The horse wasn’t what brought tears to my eyes, though. It was this one: ‘A Dying Tree, its Trunk Covered with Brambles, Beside a Fence’, about 1618, by Peter Paul Rubens (though experts are divided as to whether it’s by Rubens or Van Dyck).

The label explained that the drawing is made with a combination of materials: pen and brown ink; red and black chalk, with greenish-brown watercolour, touches of opaque watercolour and possibly oil paint. As with the horse, the drawing is a study for a larger painting. Rubens’ Landscape with a Boar Hunt, now held at the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden.

We see a tall, curving trunk of a tree emerging from a dark undergrowth. Its branches are bare, but all around it is covered in leaves, crawling up its spine, embracing it, possibly cradling its inevitable fall. The leaves fade in and out of focus, like a magnifying glass is passing over the surface of the drawing while we look at it. The undergrowth is dense and dark with cross-hatching. It reminded me of an oak tree I developed a fascination with when my mum was dying. While she was in hospital, I’d pass the time at walking near her home, watching the landscape blossom from late spring to the height of summer, this explosion of nature and life totally at odds with the personal turmoil we were experiencing.

This special tree is a patchwork of life and death. Some branches are spindly and bare, but other parts of it are thriving, covered with masses of green, bright growth, healthy leaves shining in the sun. To this day, whenever I visit my dad, I check on the tree to see how it’s doing. It’s just a short walk from where my mum is buried.

There is something comforting in being reminded that death and life coexist. Nature knows this: the ivy thrives on the branches of a dying tree, and dead wood itself is a great source of shelter for insects and is home to fungi. When a tree dies, the light that reaches down can cause huge spurts of growth on the forest floor beneath. Back in the early 1600s, Rubens took the time to observe this, laboured over it with intense detail to create what is now considered to be one of the greatest nature studies produced in Europe in the 17th century. Little did he know that 400 years later, his study of life and death would bring tears to the eyes of an observer, because it reminded her of someone, something, a time and a place, lodged in memory.

That, ultimately, is the beauty and meaning of art for me: every time you look at a picture, you bring the whole weight of associations of images, places and people you have encountered before along with you. It will mean something unique and distinct to everyone. Sometimes, it might just be a picture. Other times, it might be a whole lot more.