I was in London last weekend, and with the cultural cul-de-sac of January now over, I was spoilt for choice as to what art to see. Exhibitions including Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance at the V&A and Alice Neel: Hot Off the Griddle at the Barbican were clamouring for my attention. But instead, I picked a small exhibition at one of London’s ‘secret’ treasures – the Estorick Collection in Islington.

I don’t get art sometimes. Not perhaps the stance you’d immediately associate with someone claiming to be an art blogger. But what I really mean is I don’t always understand why I like what I like. Giorgio Morandi’s work is quiet, steady, pastel-coloured, and consists mainly of still lifes of vases. Writing it now, it doesn’t sound particularly scintillating. Luckily my pal trusted my artistic judgement and, coupled with the fact that that London postcode is particularly strong on post-gallery cake options, we headed along.

For the exhibition, the Estorick Collection has paired up with the Magnani-Rocca Foundation, combining both the Estorick’s own collection of etchings by Morandi, and the Foundation’s more extensive collection of paintings. Magnani was a persistent collector over the course of his and Morandi’s lives, and the letters between them on display in the exhibition provide an interesting insight into the artist-patron relationship.

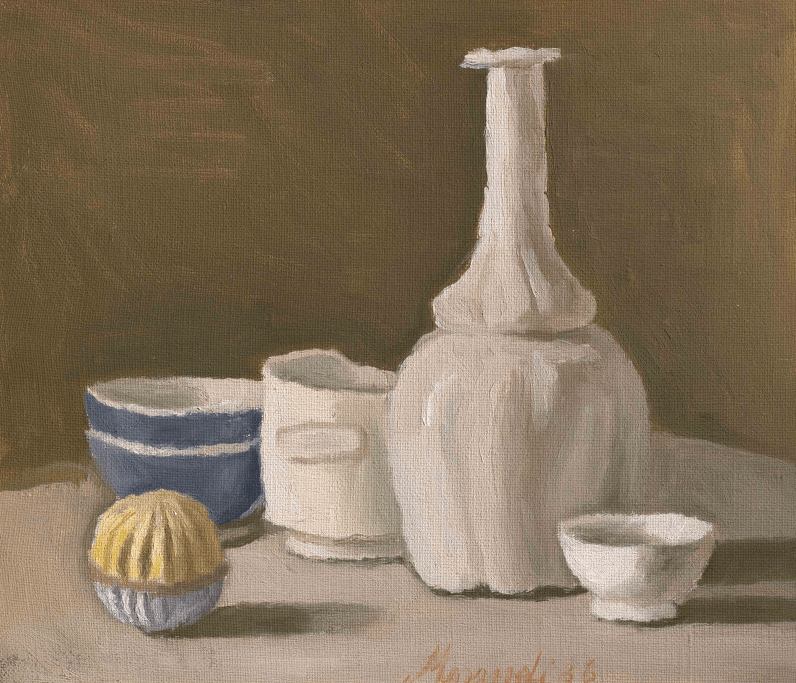

The exhibition was small, made up of only a few rooms, which allows you to focus on each work in its own time, and I think these sorts of artworks need some time. There they were, lined up in neat rows along the white walls. Morandi’s persistent, almost obsessive, repetitive paintings of vessels. Vases, cups, bottles, all stand in grey and brown and pink arrangements. This should not be that interesting, but somehow I found myself under their slow spell.

Artists over the decades have been fascinated by Morandi, and while looking at the paintings in front of me, I was reminded of a film, Still Life by Tacita Dean, made in 2009 after she spent time in the Bologna apartment where Morandi lived and worked for over 50 years. The film focuses on the measurements and careful markings found on the paper Morandi placed underneath his objects. These traces have a kind of magic to them, the same magic held by the objects, the empty vessels he returned to again and again.

I’ve long been a fan of still lifes, and by this, I mean the grand ones from the 17th century that you can find the National Gallery or the Wallace Collection. They are voluptuous, excessive, violent even. Full of reminders of life and death, tables groaning with the excess of food and silverware. Looking at these paintings is a visual treasure hunt, like reading Where’s Wally. Is that a monkey in the corner?

Morandi’s are the opposite. They are sort of dry and dusty. They are objects which hint at a precious use or existence but don’t give much else away. There are no extraneous distractions. It is not the sort of art that ‘performs’ well in the Instagram age, but there is a joy in this stillness. Up close, the objects are scrubby and mottled, the scratches in the paint are plainly obvious. But then, you take a few steps back and they meld and resolve, like a key change from minor to major.

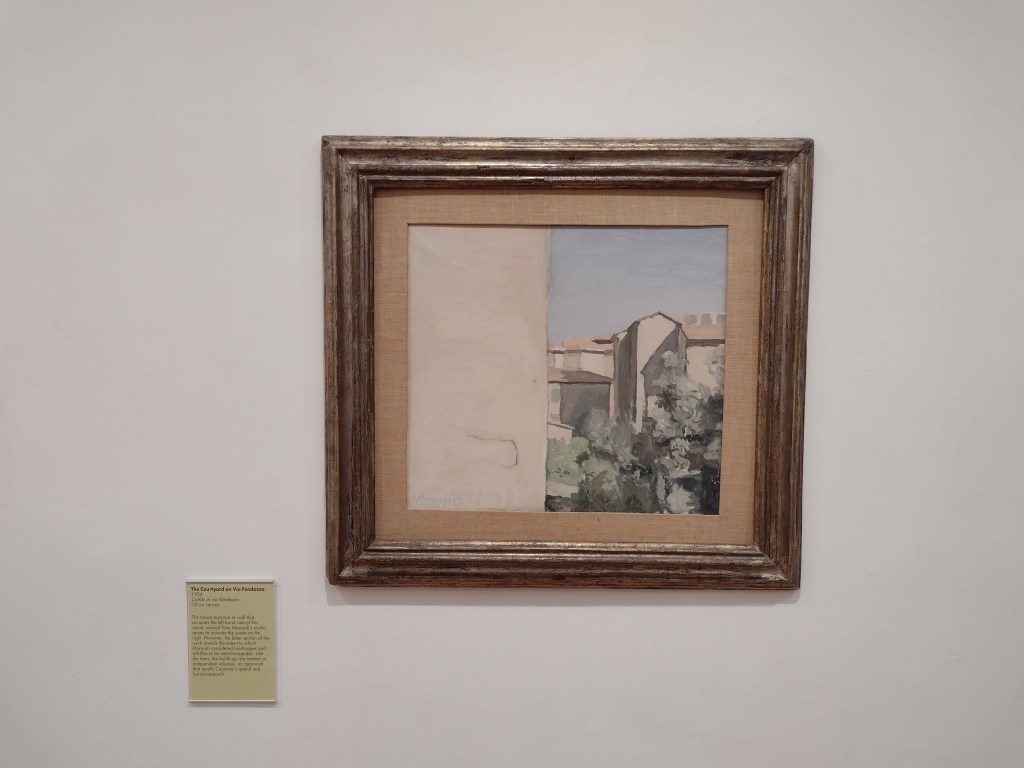

The only photo I took, shows The Courtyard on Via Fondazza (1954), a painting of some buildings and trees next to an enormous blank space on the left, which almost looks like totally untreated canvas, but actually depicts the empty side of a windowless building. It’s the space Morandi gives his subjects that I find satisfying to observe, and the exhibition wall text suggested similarities with Cézanne’s approach to space and form.

Perhaps this parallel with Cézanne is what endears me to Morandi so much. Years ago, I went to a Cézanne exhibition in Oxford where I bought a postcard of his work Three Pears (1889-90). After the show, a friend of a friend was bemused by it all: “I don’t get it. It’s just pears?”. I didn’t really know what to say. Yes, they are pears. But they are very lovely pears?

More and more these days, if I try to interrogate what I like about looking at art, it boils down to how it makes me feel. The feelings lead the way. After a while of walking around the exhibition wondering why Morandi was so obsessed with empty vessels, I decided to stop wondering why and just enjoyed the tranquillity, stillness and peace that looking at these quiet paintings can bring.

There’s a poem by Philip Larkin my Mum loved called Church Going, where he describes encountering an old abandoned church, and he doesn’t know why, but it means something to him. He says, “it pleases me to stand in silence here”, and that’s what came to mind looking at these small, intimate paintings. Sometimes standing, looking and feeling is enough. No other justifications or explanations necessary.

Brilliant!

LikeLike