I am standing in a light-filled room, one that is almost silent. The walls are white, the ceiling is high. Across the middle of the space, a huge diagonal tapestry floats, seemingly hovering, swaying slightly. It is made of the lightest of materials, silk panels hang there, lightly stitched together, suspended.

I am in a gallery for the first time in months, in a town I don’t know well. I’m looking at Emma Talbot’s Ghost Calls, created specifically for the main exhibition space at Dundee Contemporary Arts. It feels really good to be back.

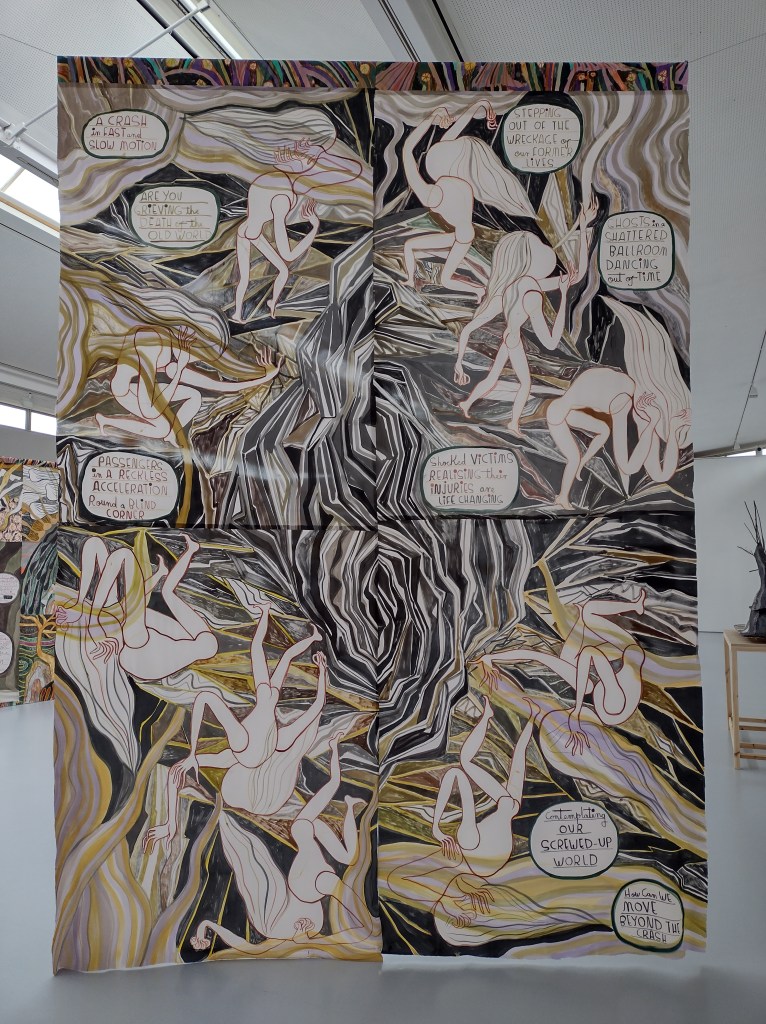

The thing I notice first about this display is the colour palette: greens, ochre, rusty red, greys and creamy white. The repeated tones help to conjure the feeling that we have entered a specific world. There is a narrative here: the first work you encounter, also a large silk tapestry, depicts an unnamed disaster that has shattered the earth and turned it upside down. There are ghostly white bodies everywhere, positioned at strange angles and holding their heads in their hands. Scattered speech bubbles tell us more: ‘passengers in a reckless acceleration round a blind corner’; ‘a crash in fast and slow motion’.

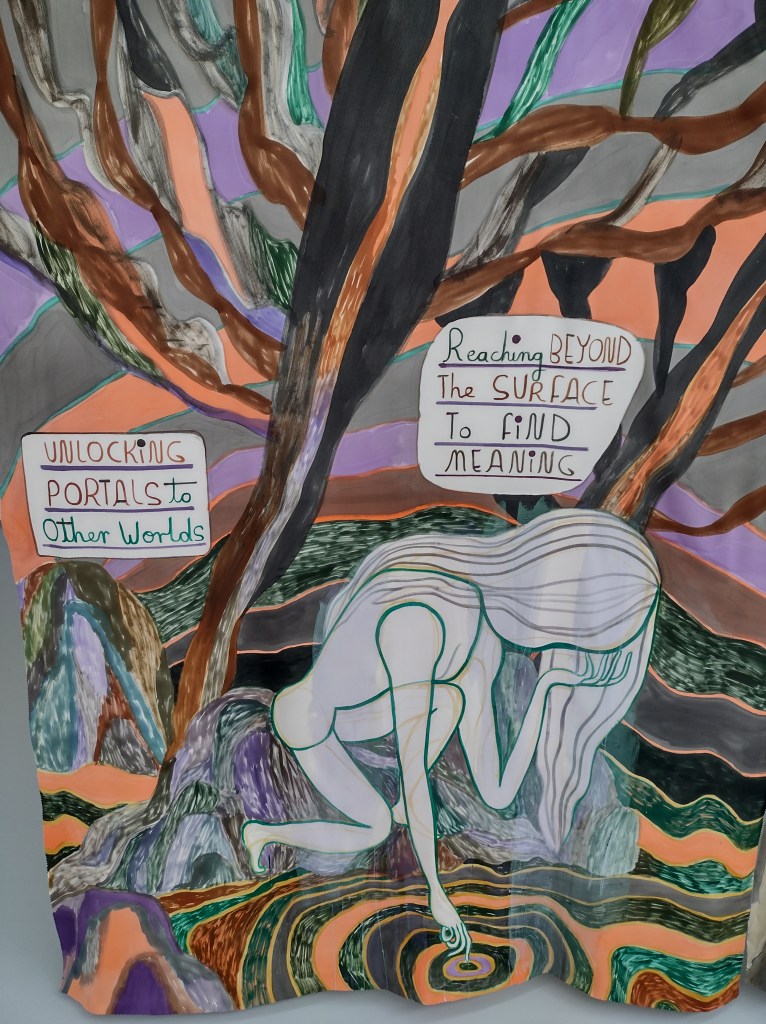

The centrepiece, a large tapestry that bisects the room, tells the story of what happens after the cataclysmic crash. Text in the first panel both questions and explains: ‘Do you hear ghost calls? A teary lament for human existence. A shout out to the living to take more care of themselves, of the world, of each other.’ I like these little ghostly souls with their long, wavy hair. The way they journey through an unknown landscape, little disembodied heads blowing long trumpets – or are these trees lying on their sides?

Though the story is about processing collective trauma, looking around me, I feel surrounded by a complete sense of calm and serenity, like a blanket has settled over the entire room. Something in the fragility of these artworks makes engaging with them a very tender encounter. Even calling the largest works ‘tapestries’ feels wrong, because that conjures up images of heavily-embroidered, thick wall hangings, decorating old castles and torchlit halls. Here, there is a palpable lightness.

The drawings are my favourite. Small-scale and pinned to the wall, they exist almost completely without ceremony: these are pages from sketchbooks. There is no glazing, there are no frames. Everything feels very immediate, right in front of me and so utterly delicate – the papers are handmade.

When researching for this exhibition, Talbot came to Dundee and was struck by the paintings at the local museum, the McManus. You can see here her fascination with The Riders of the Sidhe by John Duncan, one of the collection’s most famous paintings, a work thick with symbolism and arcane magic, and of great importance in the Celtic Revival movement. I had just been to the McManus and was admiring it too, so the connections felt particularly present in Talbot’s fine drawings of mythical beasts, a connection that was reinforced by the sense that her tapestries represent a linear journey, one with a similarly ambiguous destination.

There were five sculptures dotted around the exhibition, but these struck me as out-of-place, needless add-ons to the main body of work. The stuffed figurines were 3D versions of the ghost characters, made from a kind of velour material, with crudely kirby-gripped wigs and random accessories (a dream catcher, a willow tree). To me, they looked clumsy and jarred displeasingly with everything else, which was so finely drawn and meticulously put together.

A much more successful use of a different medium was the animated 14-minute film Keening Songs, where figures of women move through a landscape, meeting animals and spirits, enacting a ‘keening,’ a mourning ritual associated with old Gaelic communities in Scotland and Ireland. These stories were enchanting, layered with poetry and intrigue, and the exhibition as a whole suggested that we will have to enact our own keening, as we journey beyond the global trauma of the pandemic. Perhaps art can be a tool in that process?

I was visiting my second gallery of the day, for the first time in over a year, and my stamina was wavering. Yet despite the inevitable ‘museum back’, I was here at last, looking at new art in all its freshness. I felt so much gratitude for this place, these artworks, that they existed right here in front of me, without the intermediary of a screen. There is an undeniable physicality to the experience of looking, and looking carefully, one that can make the viewer feel truly present, truly awake and alive for the first time in a long time.