Last week I spent a really nice chunk of time hanging out with the youngest member of my family. My nephew is two and he’s great company. He’s how I want to be: curious, reflective, eager for fun and a sponge for new information. With his wide-eyed wonderment, he has taught me how to look at art again after a long, enforced break (otherwise known as lockdown).

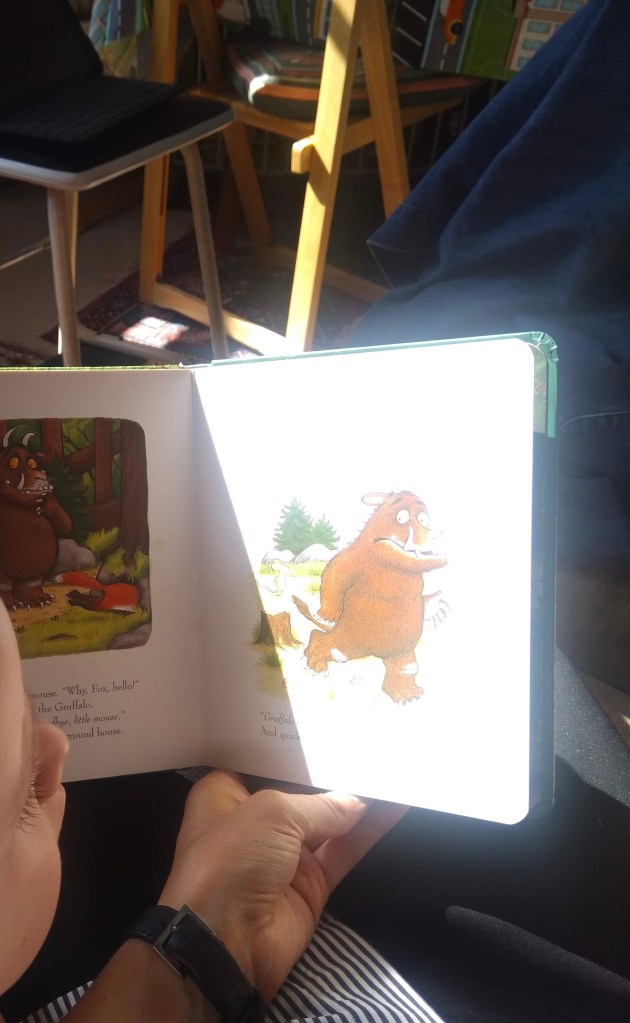

We read books together and looked at the pictures (me reading, both of us looking). Illustration is amazing, and I think a severely underrated form of art. I’m extremely lucky that in my day job, I interact with children’s books on a regular basis. Children’s books are some of the most accessible, universally loved and widely appreciated ways we experience art. The stories fascinate us, but the images are what portray and communicate the joy and terror of the narratives to young minds who cannot yet read or form sentences themselves. Fearfully gazing at the Gruffalo’s long black tongue and terrible teeth, or admiring the crisp and clear (read Scandi) aesthetic in Jon Klassen’s I Want My Hat Back, we carry the pictures with us long after the words have faded from memory.

Some of the most memorable books from my childhood were about looking at details. I was raised on books by Janet and Allan Ahlberg, searching for the characters and minuscule, meticulously written lost letters in The Jolly Postman was my delight. Later, The Most Amazing Night Book by Robert Crowther was my favourite. My nephew is also seemingly enthralled by the details. His favourite thing to do is to ask “Who’s dat?”, pointing excitedly at tiny ladybirds, trees, rocks, main characters, random piles of hay, clothes and anything else that catches his eye. Anyone who has interacted with children regularly will tell you they are incredibly perceptive and observant. Sometimes surprisingly so. They can see and sense things adults can’t.

Last week, along with hanging out with my family I also went to a gallery for the first time in six months. After trawling the internet and realising most places in London had been booked out long before by far better-organised art lovers, I managed to get a midday slot at the Wallace Collection, one of my favourite places to see art, as well as admire luxurious furnishing (and pretend I’m part of eighteenth century aristocracy). I would probably go to see the silk wall hangings alone.

I was so happy to have a slot, but despite really friendly staff and the safety measures that had been introduced, it wasn’t the most relaxing experience. It was a pressing reminder that we’re all still working through the anxieties this pandemic has produced. That the new normal isn’t going to be as good as the old normal for quite a while.

A one way system was in place and there were capacity limits on all of the rooms on the route, which created the slightly unpleasant feeling of being on a conveyor belt. Somewhat obliged to wait for those in front without pressuring them, but not wanting to take too long, disrupt the flow or be left behind, stuck in a swirling eddy without being able to rejoin the main current of my fellow gallery-goers. Not the best atmosphere for being absorbed by and for absorbing art.

I spent the first part of my visit worrying about the choreography of my movements between my fellow observers, concerned I was getting too close, getting mildly annoyed with pushy people behind me. But then I saw an oil painting, Still Life With A Monkey, attributed to Jan Jansz de Heem (c.1670-95), that made me stop in my tracks. I thought about my nephew, how much he would love looking at the cornucopia of riches in the painting and examining all the elements, individually interrogating their form and purpose. I stepped off the conveyor belt and just looked.

The spiral of lemon peel, the oysters, the mushrooms scattered on the table, the oozing pomegranate, the jug on its side, the tankard on its side, the bright white cloth, the monkey?! This kind of artwork demands your time, forces your eye to wander. We understand that still life paintings are often laced with double or even triple meanings (broken column = transitory nature of human life), but just looking at the surface level composition of what is there, without any further knowledge of iconography or semantics, is a pleasure in itself. The brightness of the lobster, the chaos and excess of it all, the way the food packs 7/8ths of the entire canvas, the needlessly dramatic sky behind. The above is my photo taken on the day, but there’s a brighter, slightly yellowy version of the painting here if you want to look more closely at the details.

Much of what drives my blog and my Instagram is a need and a wish to celebrate the everyday, to encourage others to read the notes in the margins, to slow down and enjoy colours and contrasts, patterns, eccentricities, particularly of city life. We can apply this attitude to great paintings in grand houses too. We think we know still life paintings. I imagine they’re the paintings most readily walked past without so much as a second glance because they are rarely super-famous showstoppers — but let’s take this opportunity to recognise how very bizarre and beautiful they are.

When we return to art galleries, they might not be the same as they were. But if we remember to approach art with curiosity, to take time, and notice the details, even if we haven’t got the brain space to work out what they mean, they can bring us both joy and a little peace. As from now, I’ll be adopting the “Who’s dat?” philosophy of close looking. That’s how I want to return to engaging with art as lockdown lifts. I’ll encourage you to do the same, but if you’re not feeling ready just yet, you can always start with The Gruffalo.

2 thoughts on “My two-year-old nephew taught me how to look at art after lockdown”