It is often said that the two prime events that modern Britain’s identity is founded upon are victory in the Second World War in 1945, and the founding of the National Health Service in 1948. With the 75th anniversary of VE day on Friday, and the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, I’ve been thinking these things through lately in the context of British identity.

I’ve been helped on with these thoughts by a film by Alberta Whittle, presented as part of Glasgow International’s Digital Programme. The film is called business as usual: hostile environment (2020), and it was made especially by Whittle for the Digital Programme, adapted from a longer commission she had been working on.

Firstly I need to tell you, that if you want to watch the film you have to do so now, because today is the last day of Gi’s Digital Programme (though hopefully Whittle’s work will be added to her website soon afterwards). I wrote about two other Gi works in the previous blog post, but I needed to sit with this one for longer, because it’s more political, and therefore by nature it is harder to write about.

This is art as activism. It encompasses huge issues, from the treatment of immigrants and the hostile environment, to the Windrush scandal, to the lack of PPE available for frontline staff because of the government’s sluggish reaction and mismanagement of the unfolding COVID-19 crisis. I’ve read it as a reflection on British identity, and the holes in the narrative of that identity. That’s a lot to fit into one artwork, a 16-minute film which pieces together archival footage, news reports, computer generated images and home-movie style footage of a family’s day out on a boat.

Despite the difficult issues broached, its juxtapositions are delicately balanced, so the imagery is not overtly violent or traumatising to watch. Painful subjects are contrasted with some beautiful footage of couples dancing from the archives of an early 1950s Britain, which then sit side by side with brief snapshots of racists marching, and National Front graffiti covering a bridge. Whittle makes use of the split screen to heighten these contrasts: a very grey-looking Britain is paired with what we assume is the clear, beautiful Caribbean sea. Towards the end, a long duet with vocals and drums raises the tension and serves to make the viewer feel uncomfortable. That’s ok though: art doesn’t exist for pleasure alone.

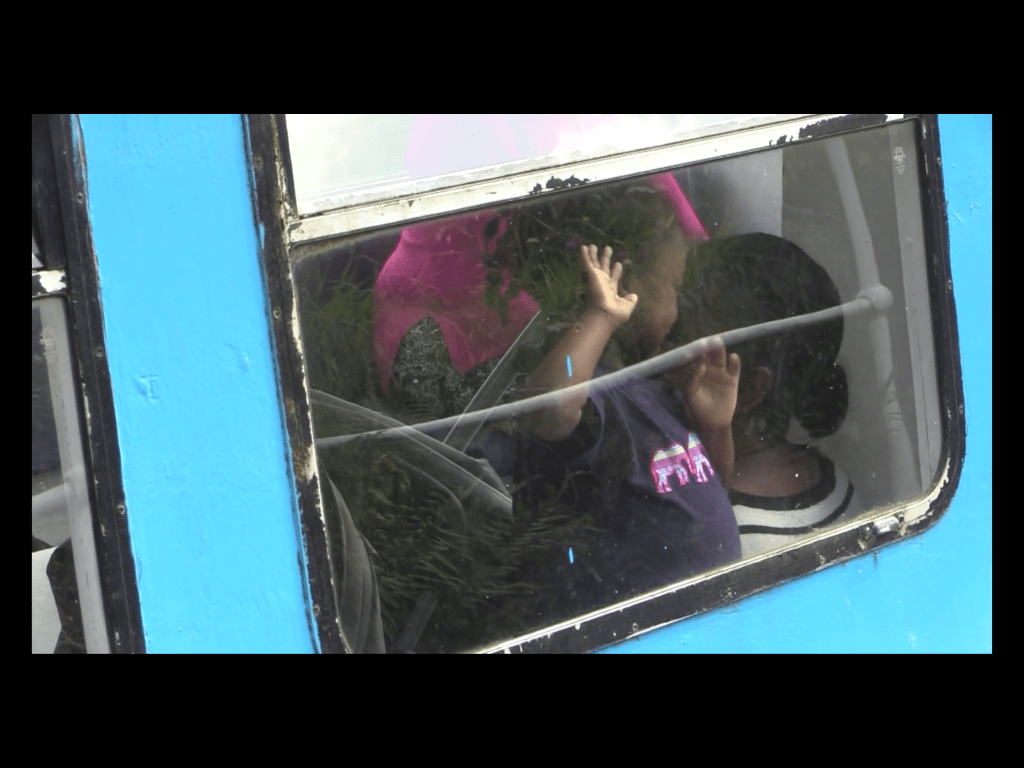

The film persistently subverts the romantic ideas around the images presented. It is partly a response to Visit Scotland’s theme for 2020, Coasts and Waters. What we (and Visit Scotland) might expect from that theme are artworks that respond to and promote Scotland’s amazing coastlines, images of peaceful landscapes with lochs reflecting mountainous scenery. In contrast, Whittle’s work looks at the role water, specifically the Glasgow Forth and the Clyde Canal, have played in the movement of people. There is one image that captures the cleverness and poignance of the film for me. A young black girl is having fun on a canal boat, smiling and knocking on the window, but a passing reflection makes it look for a moment like the window is barred, that she is imprisoned. That sent chills down my spine because of the other images I know of black people incarcerated on ships. It is the unsaid aspect which hovers over the film, including the hopeful images documenting the arrival of Empire Windrush in 1948.

There’s a lot that can be achieved by subverting, questioning and exploring the ideas that nationhood is based upon. Frankie Boyle’s Tour of Scotland, broadcast on the BBC earlier this year, is another example of digging beneath the surface of ideas of who we are. It’s no longer available on iPlayer but clips are online. The section where he talks to Councillor Graham Campbell about Glasgow’s ties to the slave trade was fascinating and, like Alberta Whittle’s business as usual: the hostile environment, works toward educating us about aspects of our past that are often swept under the rug – an ignorance that has allowed for the hostile environment to develop and the Windrush scandal to happen.

Multiple commentators have pointed out that the British government have tried to tie modern Britain’s founding ideas together with its approach to this crisis. Coronavirus has been likened to an enemy, using the language of combat, which isn’t always appropriate, effective or clear when it comes to responding to a medical emergency. The semantics of sacrifice and loyalty are invoked to try and bring us together – though clearly the extent of lives lost could have been limited, had the situation been better handled. Whittle’s film is a reminder that no amount of metaphor should be allowed to submerge that truth.

This work made me think again about how grateful I am to the artists, writers, comedians and journalists who encourage us to look deeper. The ones who question the myths, probe the difficult areas, who remind us to ‘stay alert’ to the situation unfolding around us, to the ideas and the language used to mobilise us. This has been a time of reflection and introspection for many of us, and there are some beautiful, human stories of solidarity that we can take pride in. But after it’s all over, we need a new consciousness to emerge and I want art to be at the forefront of imagining that to be possible as, to quote Whittle, “we try to live in hope” for a better future.

One thought on “Glasgow International part 2: Alberta Whittle”