There are some artworks that become wedged in your heart. You carry them with you, and mostly they lay dormant. Then occasionally they will surface from nowhere, reminding you of something you saw, read, felt years ago. For me, one of those objects is something I saw at Found, an exhibition curated by Cornelia Parker at The Foundling Museum in 2016. I must have loved it at the time, because I bought the catalogue, and that hardly ever happens.

The piece in question is by John Smith and is unassuming and profound in equal measure. As someone who believes in the necessity of encountering art in the everyday, it’s exactly the kind of work that chimes with me.

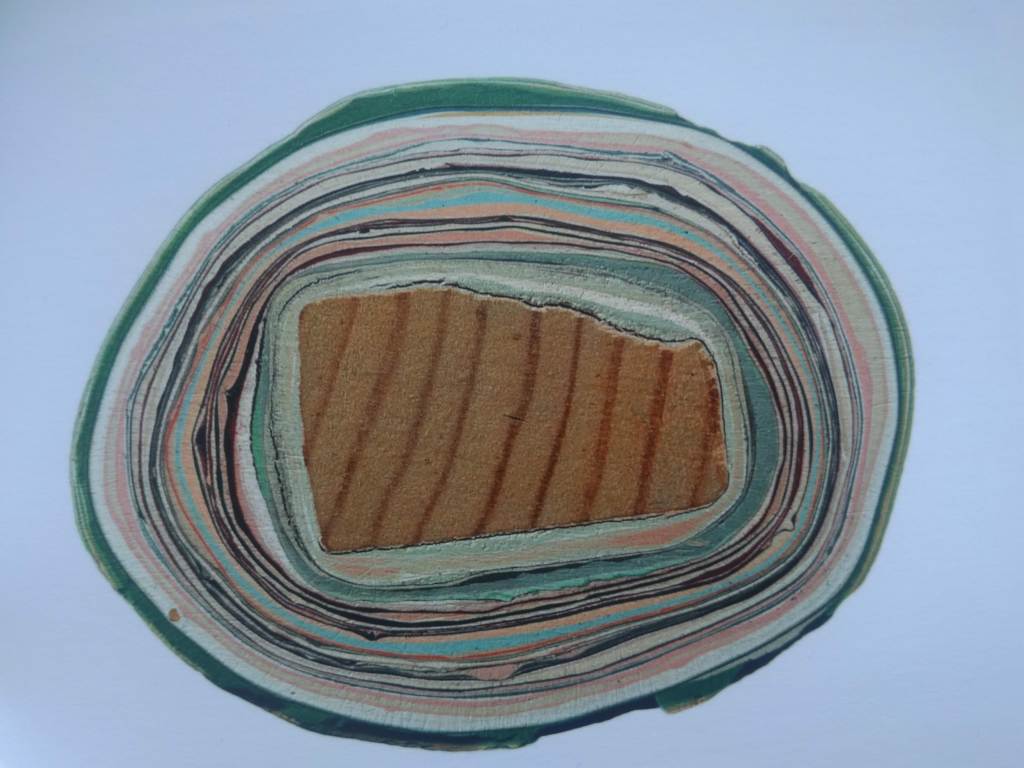

It’s difficult to know how to describe Dad’s Stick – it hovers part way between art piece, art object, tool, item, artefact. This stick belonged to the artist’s father and was used to stir paint pots for around six decades. Then, towards the end of his life, Smith’s father cut through the stick. This act revealed a cross-section of multiple layers of paint, each covering over the other, like the concentric rings of a tree. It’s a wonderful thing: documenting changes in taste, memories of rooms, snapshots of different projects, a humble memorial preserving a life story, or multiple stories. In the Found catalogue, Smith reflects that looking at the colours of the stick took him back to his childhood, “the greyish green of our 1950s kitchen cupboards and the bright orange that covered the walls of our hallway in the 1960s.” (p.122). Smith created a film to accompany the object which was also shown in the exhibition. You can see an extract of it here.

Perhaps this object resonated with me because my own childhood home had this layering too. My mum, a good seamstress with an eye for interior design, made our own curtains, and as I grew up, she covered over the childish Alice in Wonderland fabric in my bedroom with a more teenager-appropriate material. My parents don’t live there anymore, but I wonder if the current inhabitants ever puzzle over the faint colours and shapes they can see through the fabric in certain types of light. Or they may have got rid of the curtains entirely – I’ll never know.

The flip side of Dad’s Stick is the rooms themselves. Most houses have multiple layers of paint, wallpaper, and questionable decor that exists below our current surroundings. Buildings have stories, and ghosts, in their very walls. Their history is a layered patchwork of the different lives played out in their rooms.

This feels more prevalent than ever while we are all confined to our homes. I live in an Edinburgh tenement flat, part of an old stone block with one side facing the street and the other overlooking an enclosed courtyard at the back. Muffled voices through walls, the frenzy of a washing machine from the flat next door, the occasional footsteps in the hallway are all part of the daily routine. They were always there, but noticing them, and their closeness, is unavoidable now. I see people smoking out of their windows, they see me moving from room to room, chasing the sun as it graces different parts of the flat throughout the day, we watch people hanging out their washing and cats prowling in the overgrown backyard.

Being at home all the time has reminded me of these layers of lives and histories we live alongside and we contribute towards. Artworks like this one can help us process these situations, reminding us we are all part of the layering process, reassuring us that people lived here before, and they will again once we move on.